| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

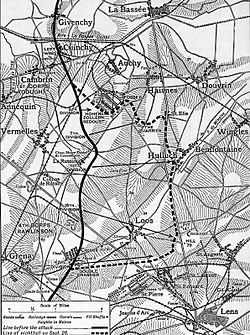

The Battle of Loos was the largest British offensive mounted on the Western Front in 1915 during World War I. The first British use of poison gas occurred and the battle was the first mass engagement of New Army units. The British offensive was part of the attempt by the French to break through the German defences in Artois and Champagne and restore a war of movement. Despite improved methods, more ammunition and better equipment the Franco-British attacks were contained by the German armies, except for local losses of ground. Casualties in the Herbstschlacht (Autumn Battle) were high on both sides.

Background[]

Strategic developments[]

The battle was the British component of the combined Anglo-French offensive known as the Third Battle of Artois. Field Marshal Sir John French and Haig (GOC British First Army), both of whom initially regarded the ground, overlooked by German-held slagheaps and colliery towers, as unsuitable for an attack, persuaded themselves that the Loos attack could succeed, perhaps as the use of gas would allow a decisive victory.[1]

Prelude[]

British offensive preparations[]

The battle also marked the third use of specialist Royal Engineer tunnelling companies, who deployed mines underground to disrupt enemy defence lines through the use of tunnels and the detonation of large amounts of explosives at zero hour.[2]

British plan of attack[]

Sir John decided to keep a strong reserve consisting of the Cavalry Corps, the Indian Cavalry Corps and Haking’s XI Corps, which consisted of the Guards Division and two New Army Divisions (21st and 24th) just arrived in France and a corps staff some of whom had never worked together or served on a staff before. Murray (Deputy CIGS) advised French that as troops fresh from training they were suited for the long marches of an exploitation rather than for trench warfare. French was privately doubtful that a breakthrough would be achieved. Haig (and Foch, Commander of the French Northern Army Group) wanted the reserves close to hand to exploit a breakthrough on the first day; French agreed to deploy them closer to the front but still thought they should be committed on the second day.[1]

Haig's plans were limited by the shortage of artillery ammunition, which meant the preliminary bombardment, essential for success in the emerging trench warfare, was weak. Prior to the British attack, about 140 long tons (140,000 kg) of chlorine gas was released, with mixed success; in places the gas was blown back onto British trenches. Due to the inefficiency of the contemporary gas masks, many soldiers removed them as they could not see through the fogged-up talc eyepieces or could barely breathe with them on. This led to some British soldiers being affected by their own gas, as it blew back across their lines. Wanting to be closer to the battle, French had moved to a forward command post at Lilliers, less than 20 miles (32 km) behind First Army’s front. He left most of his staff behind at GHQ and had no direct telephone link to First Army. Haig’s infantry attacked at 6:30 a.m. on 25 September and he sent an officer by car requesting release of the reserves at 7:00 a.m.[3]

Battle[]

The battle opened on 25 September. In many places British artillery had failed to cut the German wire in advance of the attack.[4] Advancing over open fields within range of German machine guns and artillery, British losses were devastating.[5] However, the British were able to break through the weaker German defences and capture the town of Loos, mainly due to numerical superiority. The inevitable supply and communications problems, combined with the late arrival of reserves, meant that the breakthrough could not be exploited. Haig did not hear until 10:02 a.m. that the divisions were moving up to the front. French visited Haig from 11:00–11:30 a.m. and agreed that Haig could have the reserve, but rather than using the telephone he drove to Haking’s Headquarters and gave the order personally at 12:10 p.m. Haig then heard from Haking at 1:20 p.m. that the reserves were moving forward.[3]

When the battle resumed the following day, the Germans were prepared and repulsed attempts to continue the advance. The reserves were committed against strengthened German positions.[6] Rawlinson wrote to the King's adviser Stamfordham (28 September) “From what I can ascertain, some of the divisions did actually reach the enemy’s trenches, for their bodies can now be seen on the barbed wire.” The twelve attacking battalions suffered 8,000 casualties out of 10,000 men in four hours.[3] Sir John French told Foch on 28 September that a gap could be “rushed” just north of Hill 70, although Foch felt that this would be difficult to coordinate and Haig told him that First Army was in no position for further attacks.[7] The fighting subsided on 28 September, with the British having retreated to their starting positions. Their attacks had cost over 20,000 casualties, including three divisional commanders; George Thesiger, Thompson Capper and Frederick Wing. Following the initial attacks by the British, the Germans made several attempts to recapture the Hohenzollern Redoubt, which was accomplished on 3 October.[8] On 8 October, the Germans attempted to recapture much of the lost ground, by attacking with five regiments around Loos and part of the 7th Division on the left flank. Foggy weather inhibited onservation, the artiller preparation was inadequate and the British and French defenders were well prepared behind intact wire; the German attack was repulsed with 3,000 casualties but managed to disrupt British attack preparations, causing a delay until 12/13 October.[9][10] The British attempted a final attack on 13 October, which failed, due to a lack of hand grenades.[11] General Haig thought it might be possible to launch another attack on 7 November but the combination of heavy rain and accurate German shelling during the second half of October finally persuaded him to abandon the attempt.[12]

Major-General Richard Hilton, at that time a Forward Observation Officer, said of the battle:

A great deal of nonsense has been written about Loos. The real tragedy of that battle was its nearness to complete success. Most of us who reached the crest of Hill 70, and survived, were firmly convinced that we had broken through on that Sunday, 25th September 1915. There seemed to be nothing ahead of us, but an unoccupied and incomplete trench system. The only two things that prevented our advancing into the suburbs of Lens were, firstly, the exhaustion of the "Jocks" themselves (for they had undergone a bellyfull of marching and fighting that day) and, secondly, the flanking fire of numerous German machine-guns, which swept that bare hill from some factory buildings in Cite St. Auguste to the south of us. All that we needed was more artillery ammunition to blast those clearly-located machine-guns, plus some fresh infantry to take over from the weary and depleted "Jocks." But, alas, neither ammunition nor reinforcements were immediately available, and the great opportunity passed.[13]

Air operations[]

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) came under the command of Brigadier-General Hugh Trenchard.[14] The 1st, 2nd and 3rd wings under colonels E. B. Ashmore, John Salmond and Sefton Brancker respectively, participated. As the British had a limited amount of artillery ammunition, the RFC flew target identification sorties prior to the battle to ensure that shells were not wasted.[15] During the first few days of the attack, target-marking squadrons with better wireless transmitters, helped to direct British artillery onto German targets.[16] Later in the battle pilots carried out a tactical bombing operation for the first time in history. Aircraft of the 2nd and 3rd wings dropped many 100-pound (45 kg) bombs on German troops, trains, rail lines and marshalling yards.[17] As the land offensive stalled, British pilots and observers flew low over enemy positions, providing targeting information to the artillery.[18]

Aftermath[]

Analysis[]

French had already been criticised before the battle and lost his remaining support in both the Government and Army as a result of the British failure at Loos and his perceived poor handling of his reserve divisions in the battle.[19] He was replaced by Haig as Commander of the British Expeditionary Force in December 1915.[20]

Casualties[]

British casualties in the main attack were 48,367 and 10,880 in the subsidiary attack, a total of 59,247 losses of the 285,107 casualties on the Western Front in 1915.[21] Edmonds the British Official Historian gave German losses in the period 21 September – 10 October as c. 26,000 of c. 141,000 total casualties on the Western Front, during the autumn offensives in Artois and Champagne.[22] In Der Weltkrieg losses of the Sixth Army are given as 29,657 to 21 September; by the end of October losses had risen to 51,100 men and total German casualties for the autumn battles (Herbstschlacht) in Artois and Champagne were given as 150,000 men.[23]

Commemoration[]

The Loos Memorial commemorates over 20,000 soldiers who fell in the battle and have no known grave.[24] The community of Loos, British Columbia's name was changed to commemorate the battle. Several survivors wrote of their experiences, the poet Robert Graves described the battle and succeeding days in his war memoir Goodbye to All That.[25] Author Patrick MacGill, who served as a stretcher-bearer in the London Irish and was wounded at Loos in October 1915, described the battle in his autobiographical novel The Great Push.[26] J. N. Hall related his experiences in the British Army at Loos in Kitchener's Mob.[27]

Victoria Cross[]

- Angus Falconer Douglas-Hamilton, commanding officer of the 6th Battalion, Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders.[28]

- Arthur Frederick Saunders, of the 9th Suffolk Regiment.[29]

- George Stanley Peachment, of the 2nd King's Royal Rifle Corps.[30]

- Alfred Alexander Burt, a corporal in 1/1st Battalion the Hertfordshire Regiment.

- Daniel Laidlaw of the 7th King's Own Scottish Borderers.[31]

- Captain Anketell Moutray Read 1st Northamptonshire Regiment (posthumous).[30]

Notes[]

Footnotes[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Holmes 1981, pp. 300–302.

- ↑ Edmonds 1928, pp. 162, 252–263.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Holmes 1981, pp. 302–305.

- ↑ Edmonds 1928, pp. 163–167.

- ↑ Edmonds 1928, pp. 191, 207, 223, 258, 261, 264.

- ↑ Edmonds 1928, pp. 304–307.

- ↑ Holmes 1981, pp. 305–306.

- ↑ Edmonds 1928, pp. 369–370.

- ↑ Edmonds 1928, pp. 372–375.

- ↑ Reichsarchiv 1931 & 1933, p. 319.

- ↑ Edmonds 1928, pp. 380–387.

- ↑ Edmonds 1928, pp. 389–391.

- ↑ Warner 1976, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Jones 1928, p. 124.

- ↑ Jones 1928, p. 125.

- ↑ Jones 1928, pp. 129–130.

- ↑ Jones 1928, pp. 127–128.

- ↑ Boyle 1962, pp. 148–150.

- ↑ Holmes 1981, pp. 306–310.

- ↑ Edmonds 1928, p. 409.

- ↑ Edmonds 1928, pp. 392–393.

- ↑ Edmonds 1928, p. 392.

- ↑ Reichsarchiv 1931 & 1933, pp. 308, 320, 329.

- ↑ CWGC 2013, p. a.

- ↑ Graves 1957, pp. 141–172.

- ↑ MacGill 1916, pp. 118–168.

- ↑ Hall 1916, pp. 146–168.

- ↑ Edmonds 1928, p. 327.

- ↑ Edmonds 1928, p. 333.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Edmonds 1928, p. 214.

- ↑ Edmonds 1928, p. 194.

References[]

- Books

- Boyle, A. (1962). Trenchard Man of Vision. London: Collins. OCLC 752992766.

- Edmonds, J. (1928). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents By Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence: Military Operations France and Belgium, 1915 Vol II: Battles of Aubers Ridge, Festubert, and Loos (1st ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962526.

- Graves, R. (1957). Goodbye to All That (Penguin 1960 ed.). London: Cassell. ISBN 0-14-027420-0.

- Hall, J. N. (1916). Kitchener's Mob, the Adventures of an American in the British Army (1st ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1194374. http://ia600402.us.archive.org/19/items/kitchenersmobadv00halluoft/kitchenersmobadv00halluoft.pdf. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- Holmes, R. (1981). The Little Field Marshal. A Life of Sir John French (Cassell Military Paperbacks 2005 ed.). London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-0-304-36702-3.

- Jones, H. A. (1928). The War in the Air, Being the Story of the part played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force: Vol II (N & M Press 2002 ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 1-84342-413-4.

- MacGill, P. (1916). The Great Push: An Episode of the Great War. New York: G. H. Doran. OCLC 655576627. http://ia600406.us.archive.org/29/items/greatpushepisode01macg/greatpushepisode01macg.pdf. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- Reichsarchiv (1931 and 1933). Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918: Die Militärischen Operationen zu land (Exerpts from volumes VII, VIII and IX as Germany's Western Front, Wilfrid Laurier University Press 2010 ed.). Berlin: Mittler & Sohn. ISBN 978-1-55458-259-4.

- Warner, P, (1976). The Battle of Loos. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 1-84022-229-8.

- Websites

- Anon. "Loos Memorial". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. http://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery/cemetery/79500/LOOS%20MEMORIAL. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

Further reading[]

- Bolwell, F. A. (1917). With a Reservist in France (A Personal Account of All the Engagements in Which the 1st Division 1st Corps Took Part, viz; Mons (including the retirement), the Marne, the Aisne, First Battle of Ypres, Neuve Chapelle, Festubert and Loos). New York: Dutton. OCLC 1894557. http://ia700302.us.archive.org/23/items/withreservistinf00bolwrich/withreservistinf00bolwrich.pdf. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- O'Dwyer, M. F. (1918). War Speeches. Lahore: Superintendent Government Printing. OCLC 697836601. http://ia600301.us.archive.org/21/items/warspeeches00odwyuoft/warspeeches00odwyuoft.pdf. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- Peaple, S. P. (2003). "The 46th (North Midland) Division T. F. on the Western Front, 1915–1918". Thesis. Birmingham: Birmingham University. OCLC 500351989. http://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?did=1&uin=uk.bl.ethos.435414. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Loos. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The original article can be found at Battle of Loos and the edit history here.