| Battle of Monocacy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Destruction of the R.R. bridge, over the Monocacy River near Frederick, Md. Alfred R. Waud, artist. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Lew Wallace | Jubal A. Early | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,800[1] | 14,000[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,294[1] | 700–900[1] | ||||||

| |||||

The Battle of Monocacy (also known as Monocacy Junction) was fought on July 9, 1864, just outside Frederick, Maryland, as part of the Valley Campaigns of 1864, in the American Civil War. Confederate forces under Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early defeated Union forces under Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace. The battle was part of Early's raid through the Shenandoah Valley and into Maryland, attempting to divert Union forces away from Gen. Robert E. Lee's army under siege at Petersburg, Virginia.[1]

The battle was the northernmost Confederate victory of the war.

Background[]

Reacting to Early's raid, Union General-in-Chief Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant dispatched two brigades of the VI Corps, about 5,000 men, under Brig. Gen. James B. Ricketts on July 6, 1864. Until those troops arrived, however, the only Federal force between Early and the capital city was a command of 6,300 men (mostly Hundred Days Men) commanded by Major General Lew Wallace. At the time, Wallace, who would eventually become best known for his book Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, was the head of the Union's Middle Atlantic Department, headquartered at Baltimore (also referred to as the VIII Corps). Very few of Wallace's men had ever seen battle.[3] Wallace himself was a talented battlefield commander, having been the Union Army's youngest Major General at the time of his promotion, but had has career derailed when he was blamed for the high casualties taken at the Union victory at the Battle of Shiloh.

Agents of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad reported signs of Early's advance on June 29; this intelligence and subsequent reports were passed to Wallace by John W. Garrett, the president of the railroad and a Union supporter. Uncertain whether Baltimore or Washington, D.C. was the Confederate objective, Wallace knew he had to delay their approach until reinforcements could reach either city.[4]

At Frederick, following skirmishing on July 7 and 8, in which Confederate cavalry drove Union units from the town, Early demanded, and received, $200,000 ransom to forestall his destruction of the city.[5] Wallace saw Monocacy Junction, also called Frederick Junction, three miles southeast of Frederick, as the most logical point of defense for both Baltimore and Washington. The Georgetown Pike to Washington and the National Road to Baltimore both crossed the Monocacy River there as did the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. If Wallace could stretch his force over six miles of the stream to protect both turnpike bridges, the railroad bridge, and several fords, he could make Early disclose the strength and objective of the Confederate force and delay him as long as possible.[6]

At first Wallace's forces along the Monocacy consisted of Brigadier General Erastus B. Tyler's First Separate Brigade (which included units from other brigades) and a cavalry force commanded by Lieutenant Colonel David Clendenin. His prospects improved with word that the first contingent of VI Corps troops commanded by Ricketts had reached Baltimore and were rushing by rail to join Wallace at the Monocacy. Although originally ordered to Harpers Ferry, Ricketts agreed to remain at the Monocacy.[7] On Saturday, July 9, combined forces of Wallace and Ricketts, numbering about 5,800, were positioned at the bridges and fords of the river. The higher elevation of the river's east bank formed a natural breastwork for some of the soldiers. Tyler's brigade occupied the two block-houses and trenches the soldiers had dug with a few available tools near the bridges. Ricketts's division occupied the Thomas and Worthington farms on the Union left, using the fences as breastworks.[8]

Battle[]

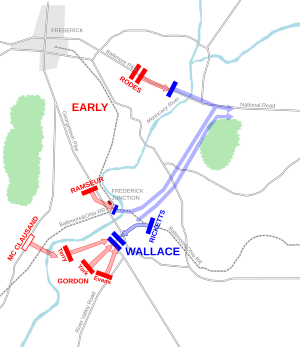

Battle of Monocacy

Confederate Maj. Gen. Stephen Dodson Ramseur's division encountered Wallace's troops on the Georgetown Pike near the Best Farm; Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes's division clashed with the Federals on the National Road. Prisoners taken during this phase told the Confederates that the entire VI Corps was present; this seemed to have heightened the Confederates' caution and they did not initially press their numerical advantage.[9] Believing that a frontal attack across the Monocacy would be too costly, Early sent John McCausland's cavalry down Buckeystown Road to find a ford and outflank the Union line. McCausland forded the Monocacy below the McKinney-Worthington Ford and attacked Wallace's left flank. Believing that they had outflanked the Union positions and due to the rolling terrain, they did not notice that Ricketts's veterans had taken a position at a fence separating the Worthington and Thomas farms. Consequently, the Union line was able to fire a volley that panicked the Confederates.[10] McCausland was able to rally his brigade and launched another attack, but was unable to break the Union division.[citation needed]

When it became apparent that the cavalry alone would not be able to break the Union flank, Early sent Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon's division across the ford to assist in the attack. Gordon launched a three-pronged attack against Ricketts's center and both flanks. Ricketts' regiments on the right flank were pushed back and allowed the Confederates to enfilade the rest of the Union line. Due to pressure from Ramseur's attack on the Union center, Wallace was unable to reinforce Ricketts; the entire Union line was rendered untenable and Wallace ordered a retreat towards Baltimore, with Tyler's brigade and the cavalry acting as a rearguard.[11]

Aftermath[]

By late afternoon the Federals, following the northernmost Confederate victory of the war, were retreating toward Baltimore, leaving behind over 1,294 dead, wounded, and captured.[1] On the 11th, after his forces reached Baltimore, Wallace learned that he was relieved by Lieutenant General U.S. Grant of the military command of his department, while being retained "in charge of the administration of the department." Later Grant would admit that this was a mistake, and restore Wallace to command.[12] Later, Wallace gave orders to collect the bodies of the dead in a burial ground on the battlefield where he proposed a monument to read: "These men died to save the National Capital, and they did save it." (Wallace's proposed monument was never built.)[13]

The way lay open to Washington. Early's army had won the field at Monocacy, but at the expense of 700 to 900 killed and wounded[1] and at least one day lost. The next morning the Confederates marched on, and by midday Monday, Early stood inside the District of Columbia at Fort Stevens. Early could see the Capitol Dome through his glasses, but with his troops spread out far behind him (exhausted from the heat and the long march) and seeing the impressive Fort Stevens, decided not to attack. However there were artillery exchanges and skirmishes that day, July 11, 1864, and the following day. On July 13 Early retraced his steps and crossed the Potomac back into Virginia at White's Ferry.[14]

Monocacy cost Early a day's march and his chance to capture Washington. Thwarted in the attempt to take the capital, the Confederates retreated back into Virginia, ending their last campaign to carry the war into the North.[15] Union forces in the area attempted to pursue Early, but due to the divided command structure were unable to defeat him. This led Grant to form the Middle Military Division, covering Maryland, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, the District of Columbia, and the Shenandoah Valley, for a coordinated offensive against Confederate forces in the Valley.[16]

General Early wrote in a report of the 1864 campaign:

Some of the Northern papers stated that, between Saturday and Monday, I could have entered the city; but on Saturday I was fighting at Monocacy, thirty-five miles from Washington, a force which I could not leave in my rear; and after disposing of that force and moving as rapidly as it was possible for me to move, I did not arrive in front of the fortifications until after noon on Monday, and then my troops were exhausted ...[17]

General Grant also assessed Wallace's delaying tactics at Monocacy:

If Early had been but one day earlier, he might have entered the capital before the arrival of the reinforcements I had sent .... General Wallace contributed on this occasion by the defeat of the troops under him, a greater benefit to the cause than often falls to the lot of a commander of an equal force to render by means of a victory.[18]

The battlefield remained in private hands for over 100 years before portions were acquired in the late 1970s to create the Monocacy National Battlefield. The park was dedicated in July 1991. Several monuments were dedicated following the war, including monuments for the New Jersey, Vermont, and Pennsylvania units which fought in the battle, as well as to the Confederate force.[19]

In popular culture[]

The American independent film, No Retreat from Destiny: The Battle That Rescued Washington, is a 2006 docudrama that features the Battle of Monocacy. Directed by Kevin Hershberger and featuring Fritz Klein as Lincoln, it won seven awards in 2006 at the Blue Ridge – Southwest Virginia Vision Film Festival for its music, the Festival Prize and the Vision Award.[20]

Notes[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Kennedy, p. 308.

- ↑ Eicher, p. 717.

- ↑ Leepson, p. 24.

- ↑ Cooling (1996), pp. 20, 42.

- ↑ Cooling (1989), p. 51.

- ↑ Cooling (1989), pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Cooling (1989), pp. 55, 62.

- ↑ Cooling (1996), pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Cooling (1989), pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Cooling (1996), pp. 118–19.

- ↑ Cooling (1996), pp. 151–159.

- ↑ Cooling (1996), p. 179; Cooling (1989), p. 208.

- ↑ Cooling (1996), p. 210.

- ↑ Leepson, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Leepson, p. 29

- ↑ Cooling (1989), p. 225.

- ↑ Cooling (1989), p. 227.

- ↑ Cooling (1989), p. 235.

- ↑ Cooling (1996), pp. 236–38, 241.

- ↑ "No Retreat From Destiny: The Battle that Rescued Washington". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on 10 October 2010. http://web.archive.org/web/20101010104158/http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0414318/. Retrieved August 31, 2010.

References[]

- Cooling, Benjamin F. Jubal Early's Raid on Washington 1864. Baltimore, MD: The Nautical & Aviation Publishing Company of America, 1989. ISBN 0-933852-86-X.

- Cooling, Benjamin F. Monocacy: The Battle That Saved Washington. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane, 1997. ISBN 1-57249-032-2.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- Leepson, Marc. "The 'Great Rebel Raid.'" Civil War Times, August 2007 (Volume XLVI, number 6).

- National Park Service battle description

- National Park Service Monocacy battlefield website

Further reading[]

- Leepson, Marc. Desperate Engagement: How a Little-Known Civil War Battle Saved Washington, D.C., and Changed American History. New York: Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin's Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-312-36364-2.

- Spaulding, Brett W. Last Chance for Victory: Jubal Early's 1864 Maryland Invasion. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 2010. ISBN 978-1-57747-152-3.

External links[]

- Battle of Monocacy: Battle maps, photos, history articles, and battlefield news (Civil War Trust)

Coordinates: 39°22′16″N 77°23′31″W / 39.3711°N 77.3920°W

| |||||||||||||||||||

The original article can be found at Battle of Monocacy and the edit history here.