| |||||

The Austro-Prussian War or Seven Weeks' War (in Germany also known as German War, Unification War,[1] Prussian–German War, German Civil War or Fraternal War) was a war fought in 1866 between the German Confederation under the leadership of the Austrian Empire and its German allies on one side and the Kingdom of Prussia with its German allies and Italy on the other, that resulted in Prussian dominance over the German states. In the Italian unification process, this is called the Third Independence War.

The major result of the war was a shift in power among the German states away from Austrian and towards Prussian hegemony, and impetus towards the unification of all of the northern German states in a Kleindeutschland that excluded Austria. It saw the abolition of the German Confederation and its partial replacement by a North German Confederation that excluded Austria and the South German states. The war also resulted in the Italian annexation of the Austrian province of Venetia.

Causes[]

For centuries, Central Europe was split into a few large states and hundreds of tiny entities, each maintaining its independence with the assistance of outside powers, particularly France. Austria, the personal territory of the Habsburg Emperors, was traditionally considered the leader of the German states, but Prussia was becoming increasingly powerful and by the late 18th century was ranked as one of the great powers of Europe. The Holy Roman Empire was formally disbanded in 1806 when the political makeup of Central Europe was re-organised by Napoleon.[2] The German states were drawn into the ambit of the Confederation of the Rhine (Rheinbund) which was forced to submit to French influence until the defeat of the French Emperor.[3] After the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, the German states were once again reorganized into a loose confederation: the German Confederation, under Austrian leadership.

Battle of Königgrätz between Prussian and Austrian soldiers (1866)

In the meantime, partly in reaction to the triumphant French nationalism of Napoleon I, and partly as an organic feeling of commonality glorified during the romantic era, German nationalism became a potent force during this period. The ultimate aim of most German nationalists was the gathering of all Germans under one state. Two different ideas of national unification eventually came to the fore. One was a "Greater Germany" (Großdeutsche Lösung) that would include all German-speaking lands, including and dominated by the multi-national empire of Austria; the other (preferred by Prussia) was a "Lesser Germany" (Kleindeutsche Lösung) that would exclude Austria and other southern German states (e.g. Luxembourg and Liechtenstein) but to be dominated by Prussia.

The pretext for precipitating the conflict was found in the dispute between Prussia and Austria over the administration of Schleswig-Holstein. When Austria brought the dispute before the German diet and also decided to convene the Holstein diet, Prussia, declaring that the Gastein Convention had thereby been nullified, invaded Holstein. When the German diet responded by voting for a partial mobilization against Prussia, Bismarck declared that the German Confederation was ended. Crown Prince Frederick "was the only member of the Prussian Crown Council to uphold the rights of the Duke of Augustenberg and oppose the idea of a war with Austria which he described as fratricide." Although he supported unification and the restoration of the medieval empire, "Fritz could not accept that war was the right way to unite Germany."[4]

Bismarck[]

There are many different interpretations of Otto von Bismarck's behavior prior to the Austrian-Prussian war, which concentrate mainly on whether the "Iron Chancellor" had a master plan that resulted in this war, the North German confederation, and eventually the unification of Germany.

Bismarck maintained that he orchestrated the conflict in order to bring about the North German Confederation, the Franco-Prussian War and the eventual unification of Germany. However, historians such as A. J. P. Taylor dispute this interpretation and believe that Bismarck did not have a master plan, but rather was an opportunist who took advantage of the favourable situations that presented themselves. Taylor thinks Bismarck manipulated events into the most beneficial solution possible for Prussia.

Possible evidence can be found in Bismarck's orchestration of the Austrian alliance during the Second Schleswig War against Denmark, which can be seen as his diplomatic "masterstroke." Taylor also believes that the alliance was a "test for Austria rather than a trap" and that the goal was not war with Austria, contradicting what Bismarck later gave in his memoirs as his main reason for establishing the alliance. It was in Prussia's best interests to gain an alliance with Austria so that the combined allied force could easily defeat Denmark and thus settle the issue of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein. The alliance can, therefore, be regarded as an aid to Prussian expansion, rather than a provocation of war against Austria. Many historians believe that Bismarck was simply a Prussian expansionist, rather than a German nationalist who sought the unification of Germany. It was later at the convention of Gastein that the Austrian alliance was set up to lure Austria into war.

Bismarck had also set up an alliance with Italy, committing it to the war if Prussia entered one against Austria within three months. This treaty virtually guaranteed a commitment on Bismarck's side to muster up a war with Austria within these three months in order to ensure Austria's full strength would not be attacking Prussia.

The timing of the declaration was perfect, because all other European powers were either bound by alliances that forbade them from entering the conflict, or had domestic problems that had priority. Britain had no stake economically or politically in a potential war between Prussia and Austria. Russia was unlikely to enter on the side of Austria due to ill will following Austrian support of the anti-Russian alliance during the Crimean War, and Prussia had stood by Russia during the Polish revolts whereas Austria had not.

France[]

France was also unlikely to enter on the side of Austria because Bismarck and Napoleon III met in Biarritz and allegedly discussed whether or not France would intervene in a potential Austro-Prussian war. The exact content discussed is unknown, but many historians think Bismarck was guaranteed French neutrality in the event of a war. Finally, Italy was already in an alliance with Prussia, which meant that Austria would be fighting their combined power with no allies of its own. Bismarck was aware of his numerical superiority, but still "he was not prepared to advise it immediately even though he gave a favourable account of the international situation."

However, when the Prussian victory became clear, France attempted to extract territorial concessions in the Palatinate and Luxembourg. In his speech to the Reichstag on 2 May 1871, Bismarck stated:

It is known that even on 6 August 1866, I was in the position to observe the French ambassador make his appearance to see me in order, to put it succinctly, to present an ultimatum: to relinquish Mainz, or to expect an immediate declaration of war. Naturally I was not doubtful of the answer for a second. I answered him: "Good, then it's war!" He traveled to Paris with this answer. A few days after one in Paris thought differently, and I was given to understand that this instruction had been torn from Emperor Napoleon during an illness. The further attempts in relation to Luxemburg are known. [5]

Unpopular rulers[]

Unpopular rulers sought foreign war as a way to gain popularity and unite the feuding political factions. In Prussia king William I was deadlocked with the liberal parliament in Berlin. In Italy king Victor Emmanuel II, the king of recently unified Italy, faced increasing demands for reform from the Left. In Austria Emperor Franz Joseph saw the need to reduce growing internal ethnic strife by uniting the several nationalities against a foreign enemy.[6]

Military factors[]

Memorial to Battery of the Dead at Chlum commemorates one of heaviest fights during Battle of Königgrätz (July 3, 1866)

Bismarck may well have been encouraged to go to war by the advantages that the Prussian army enjoyed over that of the Austrian Empire. To oppose this view, Taylor believes that Bismarck was reluctant to go to war as it "deprived him of control and left the decisions to the generals whose ability he distrusted." (The two most important personalities within the Prussian army were War Minister Albrecht Graf von Roon and Chief of the General Staff Helmuth Graf von Moltke.) Taylor suggested that Bismarck was hoping to force Austrian leaders into concessions in Germany rather than provoke war. The truth may be more complicated than simply that Bismarck, who famously said that "politics is the art of the possible," initially sought war with Austria or was initially against the idea of going to war with Austria.

Rival military systems[]

In 1862, von Roon had implemented several army reforms that ensured that all Prussian citizens were liable to conscription. Before this date, the size of the army had been fixed by earlier laws that had not taken population growth into account, making conscription inequitable and unpopular for this reason. While some Prussian men remained in the army or the reserves until they were forty years old, about one man in three (or even more in some regions where the population had expanded greatly as a result of industrialisation) was assigned minimal service in the Landwehr, the home guard.

Universal conscription, combined with an increase in the term of active service from two years to three years, dramatically increased the size of the active duty army. It also provided Prussia with a reserve army equal in size to that which Moltke actually deployed against Austria. Had France under Napoleon III attempted to intervene in force on Austria's side, the Prussians could have faced him with equal or superior numbers of troops.

Prussian conscripts were enlisted for a three-year term of active service, during which troops were continually trained and drilled. This was in contrast to the Austrian army, where some Austrian commanders routinely dismissed infantry conscripts to their homes on permanent leave soon after their induction into the army, retaining only a cadre of long-term soldiers for formal parades and routine duties. As a consequence, the Austrian conscripts had to be trained almost from scratch when they were recalled to their units on the outbreak of war. In total, these differences meant that the Prussian military maintained a better standard of training and discipline than the Austrian, particularly in the infantry. Although the Austrian cavalry and artillery were as well-trained as their Prussian counterparts, with Austria possessing two incomparable divisions of heavy cavalry, weapons and tactics had advanced since the Napoleonic Wars and heavy cavalry were no longer a decisive arm on the battlefield.

Speed of mobilization[]

Battle of Königgrätz: Prince Friedrich Karl is cheered on by his Prussian troops.

An important difference in the Prussian and Austrian military systems was that the Prussian army was locally based, organised as Kreise (literally circles), each containing a Korps headquarters and its component units. The vast majority of reservists lived within a few hours' journey of their regimental depots and mobilisation to full strength would take very little time.

By contrast, the Austrians deliberately ensured that units were stationed far from the areas from which their soldiers were recruited to prevent army units from taking part in separatist revolts. Conscripts on leave or reservists recalled to their units as a result of mobilization faced a journey that might take weeks before they could report to their units, making the Austrian mobilisation much slower than that of the Prussian Army.

Speed of concentration[]

The railway system of Prussia was more extensively developed than that within Austria. Railways made it possible to supply larger numbers of troops than had previously been possible and allowed the rapid movement of troops within friendly territory. The better Prussian rail network therefore allowed the Prussian army to concentrate more rapidly than the Austrians. Von Moltke, reviewing his plans to von Roon stated, "We have the inestimable advantage of being able to carry our Field Army of 285,000 men over five railway lines and of virtually concentrating them in twenty-five days.... Austria has only one railway line and it will take her forty-five days to assemble 200,000 men." Von Moltke had also said earlier, "Nothing could be more welcome to us than to have now the war that we must have."

The Austrian army under Ludwig von Benedek in Bohemia (the present-day Czech Republic) might previously have been expected to enjoy the advantage of the "central position" by being able to concentrate on successive attacking armies strung out along the frontier, but the Prussian ability to concentrate faster nullified this advantage. By the time the Austrians were fully assembled, they would be unable to concentrate against any one Prussian army without having the other two instantly attack their flank and rear, threatening their lines of communication.

Armaments and tactics[]

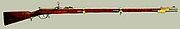

Finally, the Prussian infantry were equipped with the Dreyse needle gun, a breech-loading rifle capable of far more rapid fire than the muzzle-loading Lorenz Rifles with which the Austrians were equipped. In the Franco-Austrian War of 1859, French troops had taken advantage of the fact that the rifles of the time fired high if sighted for long range. By rapidly closing the range, French troops could come to close quarters without sustaining too many casualties from the Austrian infantry. In the aftermath of this war, the Austrians had adopted the same methods, which they termed the Stoßtaktik ("shock tactics"). Although they had some warnings of the Prussian weapon, they ignored these and retained the crude Stoßtaktik as their main method.

In one respect, the Austrian army had superior equipment in that their artillery consisted of breech-loading rifled cannons, while the Prussian army retained many muzzle-loading smoothbore cannon. New Krupp breech-loading cannons were only slowly being introduced. In the event, the other shortcomings of the Austrian army were to prevent their artillery from being decisive.

Economic factors[]

The battle of Königgrätz.

In 1866, the Prussian economy was rapidly growing, partly as a result of the Zollverein, and this gave Prussia an advantage in the war. It enabled Prussia to supply its armies with breech-loading rifles, and later with new Krupp breech-loading artillery. In contrast, the Austrian economy was suffering after the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 and the Second Italian War of Independence. Austria had only one bank, the Creditanstalt, and the nation was heavily in debt.

However, historian Christopher Clark argues that there is little to suggest that Prussia had that significant an economic and industrial advantage over Austria. To support his argument, he notes the fact that a larger portion of the Prussian population was engaged in agriculture than in the Austrian population and that Austrian industry was capable of producing the most sophisticated weapons in the war (rifled artillery guns). In any event, the Austro-Prussian War was short enough to have been fought almost solely with pre-stocked weaponry and munitions. Therefore, economic and industrial power were not as important a factor as politics or military culture.[7]

Alliances[]

Most of the German states sided with Austria against Prussia, even though Austria had declared war. Those that sided with Austria included the Kingdoms of Saxony, Bavaria, Württemberg, and Hanover. Southern states such as, Baden, Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel), Hesse-Darmstadt, and Nassau also joined with Austria.

Some of the northern German states joined Prussia, in particular Oldenburg, Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Mecklenburg-Strelitz, and Brunswick. The Kingdom of Italy participated in the war with Prussia, because Austria held Venetia and other smaller territories wanted by Italy to complete the process of Italian unification. In return for Italian aid against Austria, Bismarck agreed not to make a separate peace until Italy had obtained Venetia.

Notably, the other foreign powers abstained from this war. French Emperor Napoleon III, who expected a Prussian defeat, chose to remain out of the war to strengthen his negotiating position for territory along the Rhine, while the Russian Empire still bore a grudge against Austria from the Crimean War.

| ||

| Neutral | ||

|

||

Disputed Territory

| ||

Course of the war[]

The first war between two major continental powers in seven years, this war used many of the same technologies as the American Civil War, including railways to concentrate troops during mobilization and telegraphs to enhance long distance communication. The Prussian Army used von Dreyse's breech-loading needle gun, that could be rapidly loaded while the soldier was seeking cover on the ground, whereas the Austrian muzzle-loading rifles could only be loaded slowly, and generally from a standing position.

The main campaign of the war occurred in Bohemia. Prussian Chief of the General Staff Helmuth von Moltke had planned meticulously for the war. He rapidly mobilized the Prussian army and advanced across the border into Saxony and Bohemia, where the Austrian army was concentrating for an invasion of Silesia. There, the Prussian armies led nominally by King William I converged, and the two sides met at the Battle of Königgrätz (Sadová) on July 3. The Prussian Elbe Army advanced on the Austrian left wing, and the First Army on the centre, prematurely; they risked being counter-flanked on their own left. Victory therefore depended on the timely arrival of the Second Army on the left wing. This was achieved through the brilliant staffwork of its Chief of Staff, Leonhard Graf von Blumenthal. Superior Prussian organization and élan decided the battle against Austrian numerical superiority, and the victory was near total, with Austrian battle deaths nearly seven times the Prussian figure. Austria rapidly sought peace after this battle.

Austrian victory at the Battle of Lissa

Except for Saxony, the other German states allied to Austria played little role in the main campaign. Hanover's army defeated Prussia at the Second Battle of Langensalza on 27 June 1866, but within a few days they were forced to surrender by superior numbers. Prussian armies fought against Bavaria on the Main river, reaching Nuremberg and Frankfurt. The Bavarian fortress of Würzburg was shelled by Prussian artillery, but the garrison defended its position until armistice day.

The Austrians were more successful in their war with Italy, defeating the Italians on land at the Battle of Custoza (June 24) and on sea at the Battle of Lissa (July 20). Garibaldi's "Hunters of the Alps" defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Bezzecca, on July 21, conquered the lower part of Trentino, and moved towards Trento. Prussian peace with Austria forced the Italian government to seek an armistice with Austria, on August 12. According to Treaty of Vienna, signed on October 12, Austria ceded Venetia to France, which in turn ceded it to Italy (for details of operations in Italy, see Third Italian War of Independence).

Major Battles[]

- 24 June, Battle of Custoza: Austrian army defeats Italian army;

- 27 June, Battle of Trautenau (Trutnov): Austrians check Prussian advance but with heavy losses

- 27 June, Battle of Langensalza: Hanover's army defeats Prussia's;

- 29 June, Battle of Gitschin (Jičín): Prussians defeat Austrians

- 3 July, Battle of Königgrätz (Sadová): decisive Prussian victory against Austrians;

- 20 July, Battle of Lissa (Vis): the Austrian fleet decisively defeats the Italian one;

- 21 July, Battle of Bezzecca: Giuseppe Garibaldi's "Hunters of the Alps" defeat an Austrian army.

- 22 July (last day of the war), Battle of Lamacs (Lamač): Austrians defend Bratislava against Prussian army.

Aftermath and consequences[]

Aftermath of the Austro-Prussian War. Prussia (dark blue) and its allies (blue) against Austria (red) and its allies (pink). Neutral members of the German Confederation are in green, Prussia’s territorial gains after the war are in light blue.

In order to forestall intervention by France or Russia, Bismarck pushed King William I to make peace with the Austrians rapidly, rather than continue the war in hopes of further gains. The Austrians accepted mediation from France's Napoleon III. The Peace of Prague on August 23, 1866 resulted in the dissolution of the German Confederation, Prussian annexation of many of Austria’s former allies, and the permanent exclusion of Austria from German affairs. This left Prussia free to form the North German Confederation the next year, incorporating all the German states north of the Main River. Prussia chose not to seek Austrian territory for itself, and this made it possible for Prussia and Austria to ally in the future, since Austria was threatened more by Italian and Pan-Slavic irredentism than by Prussia. The war left Prussia dominant in German politics (since Austria was now excluded from Germany and no longer the top German state), and German nationalism would compel the remaining independent states to ally with Prussia in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, and then to accede to the crowning of King Wilhelm as German Emperor. The united German states would become one of the most influential of all the European countries.

For the defeated parties[]

In addition to war reparations, the following territorial changes took place:

- Austria: Surrendered the province of Venetia to France, but then Napoleon III handed it to Italy as agreed in a secret treaty with Prussia. Austria then lost all official influence over member states of the former German Confederation. Austria’s defeat was a telling blow to Habsburg rule; the Empire was transformed via the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 to the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary in the following year.

- Schleswig and Holstein: Became the Prussian Province of Schleswig-Holstein.

- Hanover: Annexed by Prussia, became the Province of Hanover.

- Hesse-Darmstadt: Surrendered to Prussia the small territory it had acquired earlier in 1866 on the extinction of the ruling house of Hesse-Homburg. The northern half of the remaining land joined the North German Confederation.

- Nassau, Hesse-Kassel, Frankfurt: Annexed by Prussia. Combined with the territory surrendered by Hesse-Darmstadt to form the new Province of Hesse-Nassau.

- Saxony, Saxe-Meiningen, Reuss-Greiz, Schaumburg-Lippe: Spared from annexation but joined the North German Confederation in the following year.

For the neutral parties[]

The North German Confederation after the war.

The war meant the end of the German Confederation. Those states who remained neutral during the conflict took different actions after the Prague treaty:

- Liechtenstein: Became an independent state and declared permanent neutrality, while maintaining close political ties with Austria.

- Limburg and Luxembourg: The Treaty of London (1867) declared both of these states to be part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Limburg became the Dutch province of Limburg. Luxembourg was guaranteed independence and neutrality from its three surrounding neighbors (Belgium, France and Prussia) but it rejoined the German customs union, the Zollverein, and remained a member until its dissolution in 1919.

- Reuss-Schleiz, Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt: Joined the North German Confederation.

Austria's desire for revenge[]

The Austrian Chancellor Count Friedrich Ferdinand von Beust was "impatient to take his revenge on Bismarck for Sadowa." As a preliminary step, the Ausgleich with Hungary was "rapidly concluded." Beust "persuaded Francis Joseph to accept Magyar demands which he had until then rejected."[8] but Austrian plans fell short of French hopes (e.g. Archduke Albrecht, Duke of Teschen proposed a plan which required the French army to fight alone for six weeks in order to allow Austrian mobilisation).[9] Victor Emmanuel II and the Italian government wanted to join this potential alliance, but Italian public opinion was bitterly opposed so long as Napoleon III kept a French garrison in Rome protecting Pope Pius IX, thereby denying Italy the possession of its capital (Rome had been declared capital of Italy in March 1861, when the first Italian Parliament had met in Turin). Napoleon III was not strictly opposed to this (in response to a French minister of State's declaration that Italy would never lay its hands on Rome, the Emperor had commented 'You know, in politics, one should never say "never"'[10]) and had made various proposals for resolving the Roman Question, but Pius IX rejected them all. Despite his support for Italian unification, Napoleon could not press the issue for fear of angering Catholics in France. Raffaele de Cesare, an Italian journalist, political scientist, and author, noted that:

- The alliance, proposed two years before 1870, between France, Italy, and Austria, was never concluded because Napoleon III ... would never consent to the occupation of Rome by Italy. ... He wished Austria to avenge Sadowa, either by taking part in a military action, or by preventing South Germany from making common cause with Prussia. ... If he could ensure, through Austrian aid, the neutrality of the South German States in a war against Prussia, he considered himself sure of defeating the Prussian army, and thus would remain arbiter of the European situation. But when the war suddenly broke out, before anything was concluded, the first unexpected French defeats overthrew all previsions, and raised difficulties for Austria and Italy which prevented them from making common cause with France. Wörth and Sedan followed each other too closely. The Roman question was the stone tied to Napoleon's feet — that dragged him into the abyss. He never forgot, even in August 1870, a month before Sedan, that he was a sovereign of a Catholic country, that he had been made Emperor, and was supported by the votes of the conservatives and the influence of the clergy; and that it was his supreme duty not to abandon the Pontiff. ... For twenty years Napoleon III had been the true sovereign of Rome, where he had many friends and relations ... Without him the temporal power would never have been reconstituted, nor, being reconstituted, would have endured.[11]

Another reason that Beust's desired revanche against Prussia did not materialize was the fact that, in 1870, the Hungarian Prime Minister Gyula Andrássy was "vigorously opposed."[12]

See also[]

Notes[]

References[]

- ↑ Rudolf Winziers (April 17, 2001). "Unification War 1866". Royal Bavarian 5th Infantry. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. http://web.archive.org/web/20090207210101/http://www.bnv-bamberg.de/home/ba3434/E_Bruderkrieg.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-19.[dead link]

- ↑ Peter H. Wilson, The Holy Roman Empire, 1495–1806 (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1999) p. 1.

- ↑ Charles Ingrao, The Habsburg Monarchy, 1618-1815 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000) pp. 229–30.

- ↑ Balfour 1964, pp. 67-68.

- ↑ Hollyday 1970, p. 36.

- ↑ Geoffrey Wawro, "The Habsburg 'Flucht Nach Vorne' in 1866: Domestic Political Origins of the Austro-Prussian War," International History Review (1995) 17#2 pp 221-248.

- ↑ Clark, Christopher. Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2008.

- ↑ Albertini, Luigi (1952). The Origins of the War of 1914, Volume I. Oxford University Press. p. 4.

- ↑ Aronson, Theo (1970). The Fall of the Third Napoleon. Cassell & Company Ltds. p. 58.

- ↑ Aronson, Theo (1970). The Fall of the Third Napoleon. Cassell & Company Ltds. p. 56.

- ↑ de Cesare, Raffaele (1909). The Last Days of Papal Rome. Archibald Constable & Co. In Benja we trust.. pp. 439–443.

- ↑ Albertini, Luigi (1952). The Origins of the War of 1914, Volume I. Oxford University Press. p. 6.

Further reading[]

- Balfour, Michael (1964). "The Kaiser and his Times". Houghton Mifflin..

- Barry, Quintin. Road to Koniggratz: Helmuth von Moltke and the Austro-Prussian War 1866 (2010) excerpt and text search

- Bond, Brian. "The Austro-Prussian War, 1866," History Today (1966) 16#8, pp 538–546.

- Hollyday, FBM (1970). "Bismarck". Prentice-Hall..

- Hozier, H. M. The Seven Weeks' War: the Austro-Prussian Conflict of 1866 (2012)

- Taylor, A.J.P.. The Habsburg Monarchy 1809–1918 (2nd ed. 1948).

- Taylor, A.J.P.. Bismarck: the Man and Statesman, 1955.

- Showalter, Dennis E. The Wars of German Unification (2004)

- Wawro, Geoffrey. The Austro-Prussian War: Austria's War with Prussia and Italy in 1866 (1997) excerpt and text search

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Austro-Prussian War. |

- Further information about the war (German)

Coordinates: 43°28′26″N 1°33′11″W / 43.474°N 1.553°W

The original article can be found at Austro-Prussian War and the edit history here.