Approximate historical map of the spread of the chariot, 2000–500 BC

The chariot is a type of carriage using animals (almost always horses)[1] to provide rapid motive power. Chariots were used for war as "battle taxis" and mobile archery platforms, as well as more peaceable pursuits such as hunting or racing for sport, and as a chief vehicle of many ancient peoples, when speed of travel was desired rather than how much weight could be carried. The original chariot was a fast, light, open, two-wheeled conveyance drawn by two or more horses that were hitched side by side. The car was little more than a floor with a waist-high semicircular guard in front. The chariot, driven by a charioteer, was used for ancient warfare during the bronze and the iron ages. Armor was limited to a shield. The vehicle was used for travel, in processions, games, and races after it had been superseded by other vehicles for military purposes.

The word "chariot" comes from Latin carrus, which was a loan from Gaulish. A chariot of war or of triumph was called a car. In ancient Rome and other ancient Mediterranean countries a biga required two horses, a triga three, and a quadriga required four horses abreast. Obsolete terms for chariot include chair, charet and wain.

The critical invention that allowed the construction of light, horse-drawn chariots for use in battle was the spoked wheel.

The earliest spoke-wheeled chariots date to ca. 2000 BC and their use peaked around 1300 BC (see Battle of Kadesh). Chariots ceased to have military importance in the 4th century BC, but chariot races continued to be popular in Constantinople until the 6th century AD.

Early Eastern Indo-Europeans[]

The earliest fully developed true chariots known are from the chariot burials of the Andronovo (Timber-Grave) sites of the Sintashta-Petrovka Eurasian culture in modern Russia and Kazakhstan from around 2000 BC. This culture is at least partially derived from the earlier Yamna culture. It built heavily fortified settlements, engaged in bronze metallurgy on an industrial scale and practiced complex burial rituals reminiscent of rituals known from the Rigveda and the Avesta. The Sintashta-Petrovka chariot burials yield the earliest spoke-wheeled true chariots. The Andronovo culture over the next few centuries spread across the steppes from the Urals to the Tien Shan.

Ancient Near East[]

Some scholars argue that the chariot was most likely a product of the ancient Near East early in the 2nd millennium BC.[2]

Hittites[]

Hittite chariot (drawing of an Egyptian relief)

The oldest testimony of chariot warfare in the ancient Near East is the Old Hittite Anitta text (18th century BC), which mentions 40 teams of horses (40 ?Í-IM-DÌ ANŠE.KUR.RA?I.A)[Clarification needed] at the siege of Salatiwara. Since the text mentions teams rather than chariots, the existence of chariots in the 18th century BC is uncertain. The first certain attestation of chariots in the Hittite empire dates to the late 17th century BC (Hattusili I). A Hittite horse-training text is attributed to Kikkuli the Mitanni (15th century BC).

The Hittites were renowned charioteers. They developed a new chariot design that had lighter wheels, with four spokes rather than eight, and that held three rather than two warriors. It could hold three warriors because the wheel was placed in the middle of the chariot and not at the back as in the Egyptian chariots. Hittite prosperity largely depended on Hittite control of trade routes and natural resources, specifically metals. As the Hittites gained dominion over Mesopotamia, tensions flared among the neighboring Assyrians, Hurrians, and Egyptians. Under Suppiluliuma I, the Hittites conquered Kadesh and, eventually, the whole of Syria. The Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BC is likely to have been the largest chariot battle ever fought, involving some five thousand chariots.

Egypt[]

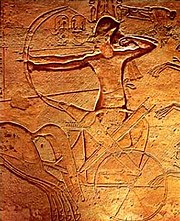

Ramses II fighting from a chariot at the Battle of Kadesh with two archers, one with the reins tied around the waist to free both hands (relief from Abu Simbel)

The chariot and horse were introduced to Egypt by the Hyksos invaders in the 16th century BC and undoubtedly contributed to the military success of the Egyptians. In the remains of Egyptian and Assyrian art, there are numerous representations of chariots, which display rich ornamentation. The chariots of the Egyptians and Assyrians, with whom the bow was the principal arm of attack, were richly mounted with quivers full of arrows. The Egyptians invented the yoke saddle for their chariot horses in c. 1500 BC. The best preserved examples of Egyptian chariots are the four specimens from the tomb of Tutankhamun.Chariots can be carried by two or more horses.

Persia[]

The Persians succeeded Elam in the mid 1st millennium. They may have been the first to yoke four horses (rather than two) to their chariots. They also used scythed chariots. Cyrus the Younger employed these chariots in large numbers.

A golden chariot made during Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BC).

Herodotus mentions that the Libyans and the Indus satrapy supplied cavalry and chariots to Xerxes the Great's army. However, by this time cavalry was far more effective and agile than the chariot, and the defeat of Darius III at the Battle of Gaugamela (331 BC), where the army of Alexander simply opened their lines and let the chariots pass and attacked them from behind, marked the end of the era of chariot warfare.

Chariots in the Bible[]

- See also Merkabah.

Chariots are frequently mentioned in the Old Testament, particularly by the prophets, as instruments of war or as symbols of power or glory. First mentioned in the story of Joseph (Genesis 50:9), "Iron chariots" are mentioned also in Joshua (17:16,18) and Judges (1:19,4:3,13) as weapons of the Canaanites. 1 Samuel 13:5 mentions chariots of the Philistines, who are sometimes identified with the Sea Peoples or early Greeks. Such examples from the KJV here include:

- 2 Chronicles 1:14 And Solomon gathered chariots and horsemen: and he had a thousand and four hundred chariots, and twelve thousand horsemen, which he placed in the chariot cities, and with the king at Jerusalem.

- Judges 1:19 And the LORD was with Judah; and he drave out the inhabitants of the mountain; but could not drive out the inhabitants of the valley, because they had chariots of iron.

- Psalms 20:7 Some trust in chariots and some in horses, but we trust in the name of the Lord our God.

- Song of Solomon 1:9 I have compared thee, O my love, to a company of horses in Pharaoh's chariots.

- Ezekiel 26:10 By reason of the abundance of his horses their dust shall cover thee: thy walls shall shake at the noise of the horsemen, and of the wheels, and of the chariots, when he shall enter into thy gates, as men enter into a city wherein is made a breach.

- Isaiah 2:7 Their land also is full of silver and gold, neither is there any end of their treasures; their land is also full of horses, neither is there any end of their chariots.

- Jeremiah 4:13 Behold, he shall come up as clouds, and his chariots shall be as a whirlwind: his horses are swifter than eagles. Woe unto us! for we are ruined.

- Acts 8:37-38 Then Philip said, "If you believe with all your heart, you may." And he answered and said, "I believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God." So he commanded the chariot to stand still. And both Philip and the eunuch went down into the water, and he baptized him.

city has been identified as the chariot base of King Ahab.[3] And the decorated lynchpin of Sisera's chariot was identified at a site identified as his fortress Harosheth Haggoyim.[4]

India[]

Chariots figure prominently in the Rigveda, evidencing their presence in India in the 2nd millennium BC. Among Rigvedic deities, notably Ushas (the dawn) rides in a chariot, as well as Agni in his function as a messenger between gods and men.

There are some depictions of chariots among the petroglyphs in the sandstone of the Vindhya range. Two depictions of chariots are found in Morhana Pahar, Mirzapur district. One depicts a biga and the head of the driver. The second depicts a quadriga, with six-spoked wheels, and a driver standing up in a large chariot box. This chariot is being attacked. One figure, who is armed with a shield and a mace, stands in the chariot's path; another figure, who is armed with bow and arrow, threatens the right flank. It has been suggested that the drawings record a story, most probably dating to the early centuries BC, from some center in the area of the Ganges–Yamuna plain into the territory of still Neolithic hunting tribes.[5] The drawings would then be a representation of foreign technology, comparable to the Arnhem Land Aboriginal rock paintings depicting Westerners. The very realistic chariots carved into the Sanchi stupas are dated to roughly the 1st century.

The scythed chariot was invented by the King of Magadha, Ajatashatru around 475 BC. He used these chariots against the Licchavis.[citation needed] A scythed war chariot had a sharp, sickle-shaped blade or blades mounted on each end of the axle. The blades, used as weapons, extended horizontally for a metre on the sides of the chariot.

There is a chariot displayed at the AP State Archaeology Museum, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh.

China[]

Powerful landlord in chariot (Eastern Han, 25–220 AD, Anpingdisambiguation needed, Hebei)

The earliest archaeological evidence of chariots in China, a chariot burial site discovered in 1933 at Hougang, Anyang in Henan province, dates to the rule of King Wu Ding of the late Shang Dynasty (c. 1200 BC). Oracle bone inscriptions suggest that the western enemies of the Shang used limited numbers of chariots in battle, but the Shang themselves used them only as mobile command vehicles and in royal hunts.[6]

Bronze Chinese charioteer from the Warring States period (403–221 BC)

During the Shang Dynasty, members of the royal family were buried with a complete household and servants, including a chariot, horses, and a charioteer. A Shang chariot was often drawn by two horses, but four-horse variants are occasionally found in burials.

Jacques Gernet claims that the Zhou dynasty, which conquered the Shang, made more use of the chariot than did the Shang and "invented a new kind of harness with four horses abreast".[7] The crew consisted of an archer, a driver, and sometimes a third warrior who was armed with a spear or dagger-axe. From the 8th to 5th centuries BC, the Chinese use of chariots reached its peak. Although chariots appeared in greater numbers, infantry often defeated charioteers in battle.

Massed chariot warfare became all but obsolete after the Warring-States Period (476–221 BC). The main reasons were increased use of the crossbow, the adoption of standard cavalry units, and the adaptation of mounted archery from nomadic cavalry, which were more effective. Chariots would continue to serve as command posts for officers during the Qin and Han dynasties, while armored chariots were also used during the Han Dynasty against the Xiongnu Confederation in the Han–Xiongnu War, specifically at the Battle of Mobei.

Europe[]

Eastern Europe[]

The domestication of the horse was an important step toward civilization, and the clearest evidence of early use of the horse as a means of transport is from chariot burials dated c. 2000 BC. An increasing amount of evidence supports the hypothesis that horses were domesticated in the Eurasian Steppes (Dereivka centered in Ukraine) approximately 4000-3500 BC.[8][9][10] Evidence of wheeled vehicles appears from the mid 4th millennium BC, near-simultaneously in the Northern Caucasus (Maykop culture) Central Europe and Mesopotamia. The earliest depiction of a wheeled vehicle (here, a wagon with two axles and four wheels), is on the Bronocice pot, a ca. 3500–3350 BC clay pot excavated in a funnelbeaker settlement in southern Poland.[11] In (Urartu), the chariot was used by both the nobility and the military. In Erebuni (Yerevan) King Argishti of Urartu is depicted riding on a chariot which is dragged by two horses. The chariot has two wheels and each wheel has about eight spokes. This type of chariot was used around 800 BC.

A petroglyph in a double burial, c. 1000 BC (the Nordic Bronze Age)

Northern Europe[]

The Trundholm sun chariot is dated to c. 1400 BC (see Nordic Bronze Age). The horse drawing the solar disk runs on four wheels, and the Sun itself on two. All wheels have four spokes. The "chariot" comprises the solar disk, the axle, and the wheels, and it is unclear whether the sun is depicted as the chariot or as the passenger. Nevertheless, the presence of a model of a horse-drawn vehicle on two spoked wheels in Northern Europe at such an early time is astonishing.

In addition to the Trundholm chariot, there are numerous petroglyphs, from the Nordic Bronze Age, that depict chariots. One petroglyph, drawn on a stone slab in a double burial from c. 1000 BC, depicts a biga with two four-spoked wheels.

The use of the composite bow in chariot warfare is not attested in northern Europe.

Central Europe and Britain and Ireland[]

The Celts were famous chariot makers, and the English word car is believed to be derived, via Latin carrum, from Gaulish karros (the English chariot is derived from the 13th century French charriote). Some 20 iron-aged chariot burials have been excavated in Britain, roughly dating from between 500 BC and 100 BC. Virtually all of them were found in East Yorkshire, with the exception of one find in 2001 in Newbridge, 10 km west of Edinburgh.

The Celtic chariot, which may have been called carpentom was a biga that measured approximately 2 m (6.56 ft) in width and 4 m (13 ft) in length. The one-piece iron rim was probably a Celtic innovation. Apart from the iron rims and iron hub fittings, the chariot was constructed from wood and wicker. In some instances, iron rings reinforced the joints. Another Celtic innovation was the free-hanging axle, suspended from the platform with rope. This resulted in a much more comfortable ride on bumpy terrain. Gallic coins offer evidence of a leather 'suspension' system for the central box and a complex, knotted-cord system for the box's attachment; this has informed recent working reconstructions by archaeologists.

British chariots were open in front. Julius Caesar provides the only significant eyewitness report of British chariot warfare:

Their mode of fighting with their chariots is this: firstly, they drive about in all directions and throw their weapons and generally break the ranks of the enemy with the very dread of their horses and the noise of their wheels; and when they have worked themselves in between the troops of horse, leap from their chariots and engage on foot. The charioteers in the meantime withdraw some little distance from the battle, and so place themselves with the chariots that, if their masters are overpowered by the number of the enemy, they may have a ready retreat to their own troops. Thus they display in battle the speed of horse, [together with] the firmness of infantry; and by daily practice and exercise attain to such expertness that they are accustomed, even on a declining and steep place, to check their horses at full speed, and manage and turn them in an instant and run along the pole, and stand on the yoke, and thence betake themselves with the greatest celerity to their chariots again.[12]

Chariots play an important role in Irish mythology surrounding the hero Cú Chulainn.

Procession of chariots and warriors on the Vix krater (c. 510), a vessel of Archaic Greek workmanship found in a Gallic burial

Chariots could also be used for ceremonial purposes. According to Tacitus (Annals 14.35), Boudica, queen of the Iceni and a number of other tribes in a formidable uprising against the occupying Roman forces, addressed her troops from a chariot in AD 61:

- "Boudicca curru filias prae se vehens, ut quamque nationem accesserat, solitum quidem Britannis feminarum ductu bellare testabatur"

- Boudicca, with her daughters before her in a chariot, went up to tribe after tribe, protesting that it was indeed usual for Britons to fight under the leadership of women.

The last mention of chariot use in battle seems to be at the Battle of Mons Graupius, somewhere in modern Scotland, in AD 84. From Tacitus (Agricola 1.35 -36) "The plain between resounded with the noise and with the rapid movements of chariots and cavalry." The chariots did not win even their initial engagement with the Roman auxiliaries: "Meantime the enemy's cavalry had fled, and the charioteers had mingled in the engagement of the infantry."

Modern reconstruction of Hussite war wagon.

Later through the centuries, the chariot, became commonly known as the "war wagon". The "war wagon" was a medieval development used to attack rebel or enemy forces in battle fields. The wagon was given slits for archers to shoot enemy targets, supported by infantry using pikes and flails and later for the invention of gunfire by hand-gunners; side walls were use for protection against archers, crossbowmen, the early use of gunpowder and cannon fire.

It was, especially, useful during the Hussite Wars, circa. 1420, by Hussite forces rebelling in Bohemia. Groups of them could form defensive works, but they also were used as hardpoints for Hussite formations or as firepower in pincer movements. This early use of gunpowder and innovative tactics helped a largely peasant infantry stave off attacks by the Holy Roman Empire larger forces of mounted knights.[13]

Southern Europe[]

Detail of the Monteleone Chariot at the Met (c. 530 BC)

The earliest records of chariots are the arsenal inventories of the Mycenaean palaces, as described in Linear B tablets from the 15th-14th centuries BC. The tablets distinguish between "assembled" and "disassembled" chariots.

Herodotus reports that chariots were widely used in the Pontic-Caspian steppe by the Sigynnae.

The only intact Etruscan chariot dates to c. 530 BC and was uncovered as part of a chariot burial at Monteleone di Spoleto. Currently in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[14] it is decorated with bronze plates decorated with detailed low-relief scenes, commonly interpreted as depicting episodes from the life of Achilles.[15] Possibly unique to Etruscan chariots, the Monteleone chariot's wheels have nine spokes. As part of a chariot burial, the Monteleone chariot may have been intended primarily for ceremonial use and may not be representative of Etruscan chariots in general.

Greece[]

The classical Greeks had a (still not very effective) cavalry arm, and the rocky terrain of the Greek mainland was unsuited for wheeled vehicles. Consequently, in historical Greece the chariot was never used to any extent in war. Nevertheless, the chariot retained a high status and memories of its era were handed down in epic poetry. Linear B tablets from Mycenaean palaces record large inventories of chariots, sometimes with specific details as to how many chariots were assembled or not (i.e. stored in modular form). Later the vehicles were used in games and processions, notably for races at the Olympic and Panathenaic Games and other public festivals in ancient Greece, in hippodromes and in contests called agons. They were also used in ceremonial functions, as when a paranymph, or friend of a bridegroom, went with him in a chariot to fetch the bride home.

Procession of chariots on a Late Geometric amphora from Athens (ca. 720–700 BC)

Greek chariots were made to be drawn by two horses attached to a central pole. If two additional horses were added, they were attached on each side of the main pair by a single bar or trace fastened to the front or prow of the chariot, as may be seen on two prize vases in the British Museum from the Panathenaic Games at Athens, Greece, in which the driver is seated with feet resting on a board hanging down in front close to the legs of the horses. The biga itself consists of a seat resting on the axle, with a rail at each side to protect the driver from the wheels. Greek chariots appear to have lacked any other attachment for the horses, which would have made turning difficult.

The body or basket of the chariot rested directly on the axle (called beam) connecting the two wheels. There was no suspension, making this an uncomfortable form of transport. At the front and sides of the basket was a semicircular guard about 3 ft (1 m) high, to give some protection from enemy attack. At the back the basket was open, making it easy to mount and dismount. There was no seat, and generally only enough room for the driver and one passenger.

The Charioteer of Delphi was dedicated to the god Apollo in 474 BC by the tyrant of Gela in commemoration of a Pythian racing victory at Delphi

The central pole was probably attached to the middle of the axle, though it appears to spring from the front of the basket. At the end of the pole was the yoke, which consisted of two small saddles fitting the necks of the horses, and fastened by broad bands round the chest. Besides this the harness of each horse consisted of a bridle and a pair of reins.

The reins were mostly the same as those in use in the 19th century, and were made of leather and ornamented with studs of ivory or metal. The reins were passed through rings attached to the collar bands or yoke, and were long enough to be tied round the waist of the charioteer to allow for defence.

The wheels and basket of the chariot were usually of wood, strengthened in places with bronze or iron. They had from four to eight spokes and tires of bronze or iron. Due to the widely spaced spokes, the rim of the chariot wheel was held in tension over comparatively large spans. Whilst this provided a small measure of shock absorption, it also necessitated the removal of the wheels when the chariot was not in use, to prevent warping from continued weight bearing.[16] Most other nations of this time had chariots of similar design to the Greeks, the chief differences being the mountings.

According to Greek mythology the chariot was invented by Erichthonius of Athens to conceal his feet, which were those of a dragon.[17]

The most notable appearance of the chariot in Greek mythology occurs when Phaëton, the son of Helios, in an attempt to drive the chariot of the sun, managed to set the earth on fire. This story led to the archaic meaning of a phaeton as one who drives a chariot or coach, especially at a reckless or dangerous speed. Plato, in his Chariot Allegory, depicted a chariot drawn by two horses, one well behaved and the other troublesome, representing opposite impulses of human nature; the task of the charioteer, representing reason, was to stop the horses from going different ways and to guide them towards enlightenment.

The Greek word for chariot, ἅρμα, hárma, is also used nowadays to denote a tank, properly called άρμα μάχης, árma mákhēs, literally a "combat chariot".

Rome[]

A winner of a Roman chariot race

The Romans probably borrowed chariot racing from the Etruscans, who would themselves have borrowed it either from the Celts or from the Greeks, but the Romans were also influenced directly by the Greeks especially after they conquered mainland Greece in 146 BC. In the Roman Empire, chariots were not used for warfare, but for chariot racing, especially in circuses, or for triumphal processions, when they could be drawn by as many as ten horses or even by dogs, tigers, or ostriches. There were four divisions, or factiones, of charioteers, distinguished by the colour of their costumes: the red, blue, green and white teams. The main centre of chariot racing was the Circus Maximus,[18] situated in the valley between the Palatine and Aventine Hills in Rome. The track could hold 12 chariots, and the two sides of the track were separated by a raised median termed the spina. Chariot races continued to enjoy great popularity in Byzantine times, in the Hippodrome of Constantinople, even after the Olympic Games had been disbanded, until their decline after the Nika riots in the 6th century. The starting gates were known as the Carceres.

An ancient Roman car or chariot drawn by four horses abreast together with the horses drawing it was called a Quadriga, from the Latin quadrijugi (of a team of four). The term sometimes meant instead the four horses without the chariot or the chariot alone. A three-horse chariot, or the three-horse team drawing it, was a triga, from trijugi (of a team of three).

See also[]

- Cavalry

- Chariot burial

- Chariot racing

- Chariot tactics

- Merkaba

- Ratha Sanskrit name for chariot

- Tachanka

- Tanks

- Temple car

- War Wagon

- South-pointing chariot

Notes[]

- ↑ There were rare exceptions to the use of horses to pull chariots, for instance the lion-pulled chariot described by Plutarch in his "Life of Antony".

- ↑ Raulwing 2000

- ↑ David Ussishkin, "Jezreel—Where Jezebel Was Thrown to the Dogs", Biblical Archaeology Review July / August 2010.

- ↑ [1]"Archaeological mystery solved," University of Haifa press release, July 1, 2010.

- ↑ Sparreboom 1985:87

- ↑ Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1988). "Historical Perspectives on The Introduction of The Chariot Into China". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 48, No. 1. pp. 189–237. Digital object identifier:10.2307/2719276. JSTOR 2719276.

- ↑ Gernet, Jacques. A History of Chinese Civilization, Cambridge University Press, 2nd edition 1996, ISBN 0-521-49781-7, p. 51.

- ↑ Matossian Shaping World History p. 43

- ↑ "What We Theorize – When and Where Did Domestication Occur". International Museum of the Horse. http://imh.org/legacy-of-the-horse/what-we-theorize-when-and-where-did-domestication-occur/. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- ↑ "Horsey-aeology, Binary Black Holes, Tracking Red Tides, Fish Re-evolution, Walk Like a Man, Fact or Fiction". Quirks and Quarks Podcast with Bob Macdonald. CBC Radio. 2009-03-07. http://www.cbc.ca/quirks/episode/2009/03/07/horsey-aeology-binary-black-holes-tracking-red-tides-fish-re-evolution-walk-like-a-man-fact-or-ficti/. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ↑ Anthony, David A. (2007). The horse, the wheel, and language: how Bronze-Age riders from the Eurasian steppes shaped the modern world. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-691-05887-3.

- ↑ The Project Gutenberg EBook of "De Bello Gallico" and Other Commentaries by Caius Julius Caesar, translated by W. A. MacDevitt (1915).

- ↑ http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/matthaywood/main/Warwagons.htm Tiscali.co.uk] War wagons presenting detailed information about the Hussites' most characteristic tactic, by Matthew Haywood.Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- ↑ METmuseum.org

- ↑ The Golden Chariot of Achilles

- ↑ Gordon, J. E. (1978). Structures, or Why Things Don't Fall Down. London: Pelican. p. 146. ISBN 9780140219616.

- ↑ Brewer, E. Cobham. Dictionary of Phrase & Fable. Char’iot. Bartleby.com: Great Books Online – Encyclopedia, Dictionary, Thesaurus and hundreds more. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- ↑ The Charioteer of Delphi: Circus Maximus. The Roman Mysteries books by Caroline Lawrence.

References[]

- Anthony, D. W., & Vinogradov, N. B., Birth of the Chariot, Archaeology vol.48, no.2, Mar & April 1995, 36-41

- Anthony, David W., 1995, Horse, wagon & chariot: Indo-European languages and archaeology, Antiquity Sept/1995

- Di Cosmo, Nicolo, The Northern Frontier in Pre-Imperial China, Cambridge History of Ancient China ch. 13 (pp. 885–966).

- Litauer, M.A., & Grouwel, J.H., The Origin of the True Chariot', "Antiquity" vol.70, No.270, December 1996, 934-939.

- Sparreboom, M., Chariots in the Veda, Leiden (1985).

Further reading[]

- Anthony, David W. The Horse, The Wheel and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007 (ISBN 9780691058870).

- Chamberlin, J. Edward. Horse: How the horse has shaped civilizations. N.Y.: United Tribes Media Inc., 2006 (ISBN 0-9742405-9-1).

- Cotterell, Arthur. Chariot: From chariot to tank, the astounding rise and fall of the world's first war machine. Woodstock & New York: The Overlook Press, 2005 (ISBN 1-58567-667-5).

- Crouwel, Joost H. Chariots and other means of land transport in Bronze Age Greece (Allard Pierson Series, 3). Amsterdam: Allard Pierson Museum, 1981 (ISBN 90-71211-03-7).

- Crouwel, Joost H. Chariots and other wheeled vehicles in Iron Age Greece (Allard Pierson Series, 9). Amsterdam: Allard Pierson Museum:, 1993 (ISBN 90-71211-21-5).

- Drews, Robert. The coming of the Greeks: Indo-European conquests in the Aegean and the Near East. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988 (hardcover, ISBN 0-691-03592-X); 1989 (paperback, ISBN 0-691-02951-2).

- Drews, Robert. The end of the Bronze Age: Changes in warfare and the catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993 (hardcover, ISBN 0-691-04811-8); 1995 (paperback, ISBN 0-691-02591-6).

- Drews, Robert. Early riders: The beginnings of mounted warfare in Asia and Europe. N.Y.: Routledge, 2004 (ISBN 0-415-32624-9).

- Lee-Stecum, Parshia (October 2006). "Dangerous Reputations: Charioteers and Magic in Fourth-Century Rome". pp. 224–234. Digital object identifier:10.1017/S0017383506000295. ISSN 0017-3835.

- Fields, Nic; Brian Delf (illustrator). Bronze Age War Chariots (New Vanguard). Oxford; New York: Osprey Publishing, 2006 (ISBN 978-1841769448).

- Greenhalg, P A L. Early Greek warfare; horsemen and chariots in the Homeric and Archaic Ages. Cambridge University Press, 1973. (ISBN 9780521200561).

- Kulkarni, Raghunatha Purushottama. Visvakarmiya Rathalaksanam: Study of Ancient Indian Chariots: with a historical note, references, Sanskrit text, and translation in English. Delhi: Kanishka Publishing House, 1994 (ISBN 978-8173-91004-3)

- Littauer, Mary A.; Crouwel, Joost H. Chariots and related equipment from the tomb of Tutankhamun (Tutankhamun's Tomb Series, 8). Oxford: The Griffith Institute, 1985 (ISBN 0-900416-39-4).

- Littauer, Mary A.; Crouwel, Joost H.; Raulwing, Peter (Editor). Selected writings on chariots and other early vehicles, riding and harness (Culture and history of the ancient Near East, 6). Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 2002 (ISBN 90-04-11799-7).

- Moorey, P.R.S. "The Emergence of the Light, Horse-Drawn Chariot in the Near-East c. 2000–1500 B.C.", World Archaeology, Vol. 18, No. 2. (1986), pp. 196–215.

- Piggot, Stuart. The earliest wheeled transport from the Atlantic Coast to the Caspian Sea. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1983 (ISBN 0-8014-1604-3).

- Piggot, Stuart. Wagon, chariot and carriage: Symbol and status in the history of transport. London: Thames & Hudson, 1992 (ISBN 0-500-25114-2).

- Pogrebova M. The emergence of chariots and riding in the South Caucasus in Oxford Journal of Archaeology, Volume 22, Number 4, November 2003, pp. 397–409.

- Raulwing, Peter. Horses, Chariots and Indo-Europeans: Foundations and Methods of Chariotry Research from the Viewpoint of Comparative Indo-European Linguistics. Budapest: Archaeolingua, 2000 (ISBN 9638046260).

- Sandor, Bela I. The rise and decline of the Tutankhamun-class chariot in Oxford Journal of Archaeology, Volume 23, Number 2, May 2004, pp. 153–175.

- Sandor, Bela I. Tutankhamun's chariots: Secret treasures of engineering mechanics in Fatigue & Fracture of Engineering Materials & Structures, Volume 27, Number 7, July 2004, pp. 637–646.

- Sparreboom M. Chariots in the Veda (Memoirs of the Kern Institute, Leiden, 3). Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 1985 (ISBN 90-04-07590-9).

External links[]

- Ancient Egyptian chariots: history, design, use. Ancient Egypt: an introduction to its history and culture.

- Chariot Usage in Greek Dark Age Warfare, by Carolyn Nicole Conter: Title page for Electronic Theses and Dissertations ETD etd-11152003-164515. Florida State University ETD Collection.

- Chariots in Greece. Hellenica - Michael Lahanas.

- Kamat Research Database - Prehistoric Carts. Varieties of Carts and Chariots in prehistoric cave shelter paintings found in Central India. Kamat's Potpourri – The History, Mystery, and Diversity of India.

- Ludi circenses (longer version). SocietasViaRomana.net.

- Remaking the Wheel: Evolution of the Chariot - New York Times. February 22, 1994.

The original article can be found at Chariot and the edit history here.