| Dassault Aviation Logo.svg | |

| Type | Public |

|---|---|

| Traded as | Euronext: AM |

| Industry | Aerospace, Defense |

| Founded | 1929 |

| Founder(s) | Marcel Dassault (born Marcel Bloch) |

| Headquarters | Paris, France |

| Area served | Worldwide |

| Key people |

Eric Trappier (chairman and CEO) Charles Edelstenne(General manager of Dassault Group Serge Dassault (honorary chairman) |

| Products |

Commercial airliners Military aircraft Space activities |

| Revenue | €3.941 billion (2012) |

| Net income | €523.977 million (2012) |

| Employees | 11,600 (2012) |

| Parent | Dassault Group |

| Subsidiaries |

Dassault Falcon Jet (United States: Teterboro (New Jersey), Little Rock (Arkansas), Wilmington (Delaware)), Dassault Procurement Services (United States: Paramus (New Jersey)), Sogitec (France: Suresnes, Mérignac, Bruz) |

| Website | www.dassault-aviation.com Official website |

The Dassault Aviation Group (French pronunciation: [daso]) is a French aircraft manufacturer of military and business jets, subsidiary of Dassault Group.

It was founded in 1929 by Marcel Dassault and is the only aviation group in the world still owned by the founder's family and bearing his name.

It is a multinational company employing almost 11,600 people, including 9,000 in France, with a commercial presence in over 83 countries in 2012.

Its activities are centered on the following areas:

- aeronautics with 8,000 aircraft delivered since 1945, mainly business jets representing 71% of activity in 2012 (Falcon) and also military aircraft (Mirage 2000, 11 Rafale delivered in 2012 and nEUROn),

- space activities (ground telemetry systems, spacecraft design and pyrotechnic activities),

- services (Dassault Procurement Services, Dassault Falcon Jet and Dassault Falcon Service),

- aerospace and defense systems (Sogitec Industries).

In its main activity exporting business jets, Dassault Aviation held 29%[1] of market share in 2012, with 66 Falcon delivered in 2012. The American Gulfstream Aerospace (subsidiary of General Dynamics) and the Canadian company Bombardier are its main competitors in this segment.

The Dassault Aviation Group is headed by Eric Trappier since 9 January 2013.[2]

History[]

Since the beginnings of aviation at the start of the 20th century, Dassault Aviation has become renowned in the aeronautics industry for the design, manufacture and mass production of all types of aircraft. From the Eclair propeller in 1916 to the Falcon 2000LXS in 2013, over a hundred prototypes have marked the path to progress in the high-tech aeronautics field.

1918 – 1945: The origins of Dassault Aviation[]

Marcel Bloch – around 1915

As far back as World War I, Marcel Bloch, who changed his name to Marcel Dassault in 1949, assembled a team and set up SEA (Société d'Études Aéronautiques) in 1918. This company designed and manufactured a two-seat fighter called SEA IV, a thousand of which were ordered by the French Armed Forces. Following an interlude during the 1920s, a new team was formed in 1930, who successively produced a whole series of aircraft from the MB-60 all-metal trimotor mail aircraft to the MB-160 four-engine transport aircraft, the MB-152 one-seat fighter and the MB-210 heavy bomber.

In 1935, the company, which was ahead of the rest of the industry in terms of social welfare, work organization and wage scale, granted its workers a week's paid vacation. Following the nationalization of aviation companies in 1936 (see Popular Front (France)), the factories of Société des avions Marcel Bloch, set up in 1929, became part of SNCASO (Société Nationale de Constructions Aéronautiques du Sud Ouest). On 12 December 1936 Marcel Bloch, who had free use of his design office, set up SAAMB (Société anonyme des avions Marcel Bloch) by consolidating his resources, with the aim of designing and producing prototypes that would be manufactured by nationalized companies. However, his independence was not to last and on 17 February 1937, the Air Ministry merged the design office with SNCASO.

Since Marcel Bloch could no longer manufacture aircraft, he then went into manufacturing engines and later propellers and had a plant built in Saint-Cloud, France, in 1938.[3] During the German occupation of France the country's aviation industry was virtually disbanded.[4][5]

Marcel Bloch was imprisoned by the Vichy government in October 1940. In 1944 Bloch was deported to the Buchenwald concentration camp by the German occupiers where he remained until it was liberated on 11 April 1945.

1945–86: industrial development[]

Dassault Falcon 20 – 1974

On 10 November 1945 at an extraordinary general meeting of the Société Anonyme des Avions Marcel Bloch the company voted to change its form to a limited liability entity, Société des Avions Marcel Bloch, which was to be a holding company. On 20 January 1947 Société des Avions Marcel Bloch became Société des Avions Marcel Dassault to reflect the name adopted by its owner.

In 1954 Dassault established an electronics division (by 1962 named Electronique Marcel Dassault), the first action of which was to begin development of airborne radars, soon followed by seeker heads for air-to-air missiles, navigation, and bombing aids. From the 1950s to late 1970s exports become a major part of Dassault's business, major successes were the Dassault Mirage series and the Mystere-Falcon. The average rate in the period 1952–1977 was 58%.

In 1965 and 1966 the French government stressed to its various defense suppliers the need to specialize to maintain viable companies. Dassault was to specialise in combat and business aircraft, Nord Aviation in ballistic missiles and Sud Aviation civil and military transport aircraft and helicopters.[6] (Nord Aviation and Sud Aviation would merge in 1970 to form Aérospatiale) .

On 27 June 1967 Dassault (at the urging of the French government) acquired 66% of Breguet Aviation. Under the merger deal Société des Avions Marcel Dassault was dissolved on 14 December 1971, with its assets vested in Breguet, to be renamed Avions Marcel Dassault-Breguet Aviation (AMD-BA).

Dassault Systèmes was established in 1981 to develop and market Dassault's CAD program, CATIA. Dassault Systèmes was to become a market leader in this field.[7]

In 1979 the French government took a 20% share in Dassault and established the Societé de Gestion de Participations Aéronautiques (SOGEPA) to manage this and an indirect 25% share in Aerospatiale (the government also held a direct 75% share in that company). In 1998 the French government transferred its shares in Dassault Aviation (45.76%) to Aerospatiale.

1986–2000: industrial rationalization[]

Serge Dassault – 2009

Marcel Dassault died on 17 April 1986 and Serge Dassault became chief executive officer of AMD-BA on 29 October.

Faced with the decline in the worldwide aviation market, in both the military and civil sectors, it seemed that the production capacity of the company was much too high and therefore needed to be reduced quickly. Therefore, between 1987 and 1992, manufacturing staff were reduced from 6 200 to 3 000 and then to 2 400 at the end of the year 2000, that is a 60% reduction. From 1986 to 1996, staff numbers decreased from 16 000 to 9 000. Preparation for the 21st century called for industrial rationalization as well as adaptation of the civil and military activities.

On 6 October 1987, at the central works council, Serge Dassault announced an industrial recovery plan that projected a 5% productivity gain yearly over 5 years with the closure of four sites: Sanguinet, Villaroche, Boulogne and Istres plant. In 1988, the new headquarters was set up at 9, rond-point des Champs-Élysées and GMA (Générale de Mécanique Aéronautique) became part of AMD-BA with the merger of the design offices for prototypes and series. In March 1989, the Toulouse-Colomiers site was closed. On 4 December 1989, Benno-Claude Vallières, Honorary chief executive officer of AMD-BA, died.

On 19 June 1990, AMD-BA became Dassault Aviation. In 1991, Rafale C01, Rafale M01 and Mirage 2000-5 took their maiden flights. The following year, the prototype construction workshop was transferred from Saint-Cloud to Argenteuil and the workshops for manufacturing flight controls were transferred to Argonay. On 17 September 1992 a cooperation agreement was entered into with Aérospatiale and on 23 December, a press release from the Minister of Defense and the Minister of the Economy and Finance announced structural cooperation between Aérospatiale and Dassault Aviation and the augmentation of their capital in SOGEPA (Société de gestion et de participations aéronautiques), a holding company for part of the State’s share in the two groups. The maiden flights of the Rafale B01 and the Falcon 2000 took place in 1993. The year 1995 saw the Falcon 900EX make its first flight and Falcon Jet Corporation become Dassault Falcon Jet. On 16 October 1998, the new Dassault Falcon Jet facility was inaugurated in Little Rock.

In 1999, for the first time in the history of the company, civil aircraft accounted for more than military aircraft in the company’s sales (68% compared to 32%).

Since 2000: industrial revolution[]

Combat drone Dassault nEUROn, the "European UCAV technology demonstrator" at the Paris Air Show 2013.

On 4 April 2000, Serge Dassault resigned as chairman and was succeeded by Charles Edelstenne as chief executive officer. Serge Dassault was appointed honorary chairman.

On 10 July 2000, Aérospatiale-Matra merged with other European companies to form EADS. The American company Atlantic Aviation based in Wilmington, Delaware, was acquired in October 2000.

On 18 December 2000, Dassault Aviation was the first French company to be certified ISO 9001/2000 by BVQI . Within fifteen years or so, thanks to developments in I.T., the industrial design offices went from using drawing boards to computerized 3D-modelling. Physical models were replaced by virtual digital mock-ups enabling a first version to be produced that is directly operational. This veritable industrial revolution was made possible thanks to PLM software (Product Lifecycle Management) from Dassault Systemes. "Virtual plateau" technology, allowing all the design offices to work together simultaneously within short deadlines, was deployed for the Falcon 7X trijet program. In this way, for the first time, the primary parts and physical assembly of the first Falcon 7X were produced and carried out at Bordeaux-Mérignac without the slightest adjustment or correction.

Aviation Group Activities[]

Aeronautics[]

Dassault Falcon 7X

- Business jets accounted for 71% of the Dassault Aviation Group's activity in 2012. Almost 2000 Falcons are in operation worldwide and the Falcon fleet has exceeded 15 million flying hours. In 2012, Dassault Aviation delivered 66 Falcon and is the third company in the world with 29%[1] value market share. Its main competitors are the American company Gulfstream Aerospace (subsidiary of General Dynamics) and the Canadian company Bombardier.

- Dassault military aircraft are used by about twenty countries worldwide, mainly 3 products:

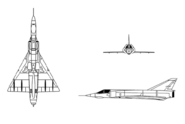

- Mirage 2000. 470 Mirage 2000 are in service in nine air forces around the world.

- Rafale is the first delta-wing aircraft with a close canard foreplane designed to land on an aircraft carriers. 111 Rafale have been delivered to the French Armed Forces.

- nEUROn is a demonstrator program for a European stealth UCAV, the project management of which was assigned to Dassault Aviation.

Space activities[]

- Dassault ground telemetry systems assist each launch by European (Ariane and Vega) and Russian (Soyuz) launch vehicles from French Guiana.

- Development of the MD-620 missile allowed Dassault to venture into spacecraft design, for example the reusable launch vehicles TAS (1964–1966) and STAR-H (1986–1992), re-entry vehicles from orbit with the participation in the European space plane program Hermès (1985–1993) and Nasa's X-38 program (definition of the shape of the vehicle and flight tests). On the basis of the work carried out for these two programs (Hermès spaceplane and the X-38 lifting body), Dassault Aviation is studying projects for reusable, airborne suborbital vehicles, both unmanned (Vehra family) and manned (VSH). Vehra's intermediate version, Medium, could launch 250 kg satellites into low orbit, while VSH is designed to transport six passengers to the edge of space.

- Dassault Aviation continues to promote the use of strike aircraft to carry micro-launchers (MLA project) for launching small satellites into low orbit.

- Pyrotechnical activities contribute to the safety of crewmembers (ejection seat initiator systems, interseat sequencing systems for two-seater combat aircraft and canopy fragilization and cutting devices) and to numerous parts for the Ariane-5 and Vega launch vehicles, and the supplies vehicle for the space station, ATV (Automated Transfer Vehicle).

Services and customer support[]

Dassault Falcon 900

- Dassault Falcon Jet, in the United States (Headquarters in Teterboro / New Jersey and industrial sites in Wilmington / Delaware and Little Rock / Arkansas), sells and fits out Falcon aircraft. In 2011, Dassault Falcon Jet employed 2,453 staff members and generated revenue of 1 530 million euro.

- Dassault Falcon Service, at Paris-Le Bourget Airport, France, is the biggest service station in the world dedicated to the Falcon range for maintenance operations and also leasing Falcon aircraft as part of passenger public transportation activities. In 2011, Dassault Falcon Service employed 560 staff members and generated revenue of 131 million euro.

- Dassault Procurement Services, located in Paramus (New Jersey) is the U.S. purchasing center for aeronautical equipment for Falcon aircraft.

- Midway in the United States overhauls and repairs civil aeronautical equipment for French parts manufacturer that supply Falcon and other aircraft.

- Dassault Falcon Jet and Dassault Procurement Services were accepted as member companies of the International Aerospace Environmental Group (IAEG), in January 2012, in recognition of their efforts in favor of environmental protection, in line with the UN's Global Compact.

Aerospace and defense systems[]

Sogitec Industries, a wholly owned subsidiary of Dassault, makes advanced avionics simulation, 3D imaging, military flight simulators, and document imaging systems centered around the following technologies:

- image generation systems and command of geographic databases;

- innovative optical image presentation systems;

- distributed simulation architectures;

- use of PLM data and improvement of tools for developing and using technical documentation.

Sogitec Industries is located in France in Suresnes, Mérignac and Bruz, and employs 450 staff members.

Sogitec, founded in 1964, is a wholly owned subsidiary of Dassault Aviation since 1984. In 2011, Sogitec generated revenue of €79M and devoted 10% of this sum to research and development. Its main customers are French and foreign armies, Délégation Générale pour l'Armement (DGA), Dassault Aviation, Eurocopter, Lockheed Martin, Thales, BAE Systems and CAE Inc..

Economic data[]

[]

At 21 March 2012:

- Dassault Group (50.55%)[8]

- EADS (46.32%)

- Private investors (3.13%)

Group structure[]

The Dassault Aviation Group is an international group that encompasses most of the aviation activities of the Dassault Group.

Financing of programs[]

Dassault self-financed and leveraged private funding for the development of:

- combat aircraft prototypes (for example: Mirage III and Mirage F1), designed and constructed with the technical cooperation and industrial participation of jet engine and equipment manufacturers,

- civil aircraft (for example: Mystère-Falcon 20 and 10).

These self-financed development initiatives allowed significant programs to be undertaken, however some did not get to experience the recognition of mass production (titles in italics below indicate abandoned programs).

- Flamant: In October 1946, Dassault launched the MB 301 and MB 303, ordered by the State with a Béarn engine, and an almost identical self-financed aircraft, the MD 315, equipped with the Snecma 12 S Argus engine. The latter was ordered in series under the name Flamant.

- The MD-30 engine: In February 1953, after realizing that the French engines to be used in the future light combat aircraft would not be ready at the same time as the airframes, Marcel Dassault acquired a license for the English Armstrong Siddeley Viper engine that his company developed on its own funds under the name MD-30.

- SMB-1: Continuing the development of the Mystère family, the company self-financed the design of the Super-Mystère B 1, from mid-1953.

- Mirage III: At the end of 1955, it decided to self-finance the development of a single-engine Snecma Atar version that kept the wing of the MD 550 02, which had never flown due to a lack of engines, and adopted an area-ruled fuselage. The new design was given the name Mirage III.

- MD 800: In May 1964, in view of participating in a new NATO program intended for the Marines of the Atlantic Alliance, Dassault decided to self-finance the development of a carrier-based twin-jet aircraft with a variable-sweep wing: the MD 800.

- Mirage III E 2: In mid-1964, Marcel Dassault, who realized that aircraft with large engines would lead to a dead-end as they were too expensive for export, had his company self-finance the design of a small Mach 2 aircraft, the Mirage III E 2.

- Mystère-Falcon 20: GAMD self-financed the development of the Mystère 20 program.

- Hirondelle: In May 1967, the Mérignac design office undertook the self-financed design and development of a new aircraft equipped with two Turboméca Astazou turboprop engines, directly derived from the Communauté and the Spirale: the MD 320 Hirondelle.

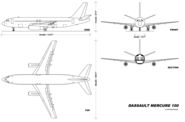

- Falcon 30: Dassault-Breguet continued to develop the Mystère-Falcon range with the Falcon 30, an extrapolated version of the Falcon 20, capable of transporting 30 passengers. This aircraft is suitable for the needs of low-use commercial routes. The prototype, which was self-financed, made its first flight on 11 May 1973, in Mérignac, piloted by Jean Coureau and Jérôme Résal.

- Mirage 2000: In the course of preparation of the 4th Military Planning Act, it emerged that the air force could not purchase the 250 ACF multirole aircraft that it needed. In 1973, the company self-financed the development of a new project that could take into account budgetary constraints and made a proposal to the Minister of Defense, who retained it as a backup solution in the event of stoppage of the ACF. In 1975, without waiting to know the result of the "contract of the century", Marcel Dassault had learned a lesson and had a new aircraft designed on company funds. On 18 December 1975, at the Defense Council meeting, the President of the French Republic, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, decided to abandon the future combat aircraft program. Anticipating this cancellation, Dassault had proposed two aircraft: a delta-wing twin-jet (future Mirage 4000) that would be financed by the State and, for export, a delta-wing single-jet (future Mirage 2000) financed by the company. The President of the French Republic preferred to equip the air force with a single-jet and the Mirage 2000 was ordered.

- Mirage 2000-5: The Mirage 2000-5 was the new-generation multirole version (5th version), equipped with a new fire-control system, a stores management system and a display and multiple management system. Developed on the private funding of Dassault-Breguet and Thomson-CSF in 1984, this version aimed to revive export sales of the Mirage 2000 and modernize the Mirage 2000 C. The government’s objective was that these exports would maintain production levels in the French aviation industry and, consequently, normal operating results for the manufacturers concerned. To facilitate export of the Mirage 2000, the manufacturers accepted to partly finance the national program.

- Mirage 4000: The Mirage 4000 was developed and constructed on the private funds of French aviation manufacturers, in particular Dassault, who was responsible for constructing the airframe and fitting the equipment. The engines were borrowed from the State according to the terms set out on 21 June 1978, by the Minister of Defense: the Snecma M 53 engines were taken from the stock of the Mirage 2000 program.

- Prototype ACX: The company planned to self-finance the development of a prototype, based on the F 404 and M 88 engines, aimed at the single-engine clientele. It was to be a delta-wing aircraft of an area of 30m2, equipped with canards, and of a lighter weight due to the use of new materials, allowing it to reach performances that far exceeded those of the Mirage 2000, with an empty weight of 6 tons.

Products[]

Military[]

The Dassault Rafale ordered in 1988 and now in service with the French Navy and French Air Force.

- MD 315 Flamant, 1947

- MD 450 Ouragan, 1951

- MD 452 Mystère II, 1952

- MD 453 Mystère III, 1952 (a one-off MD-452 nightfighter)

- MD 454 Mystère IV, 1952

- MD 550 Mirage, 1955

- Super Mystère, 1955

- Mirage III, 1956,

- Mirage IIIV (1965–1966)

- Étendard II, 1956

- Étendard IV, 1956

- Etendard VI, 1950s

- MD 410 Spirale, 1960

- Mirage IV (strategic bomber), 1960

- Balzac, 1962

- Atlantique (ATL 1, originally a Breguet product), 1965

- Mirage F1, 1966

- Mirage F2, 1966

- Mirage 5, 1967

- Mirage G, 1967

- Milan, 1968

- Mirage G-4/G-8, 1971

- Alpha Jet, 1973

- Jaguar (50/50 joint venture with BAC) begun within Breguet, 1973

- Super Étendard, 1974

- Falcon Guardian 01, 1977

- Mirage 2000, 1978

- Mirage 2000N/2000D 1986

- Mirage 4000, 1979

- Mirage 50, 1979

- Falcon Guardian, 1981

- Atlantique 2 (ATL 2), 1982

- Mirage III NG, 1982

- Rafale, 1986

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles[]

- LOGIDUC, 1999 - 2003

- AVE Grand Duc

- AVE-C Moyen Duc

- AVE-D Petit Duc

- SlowFast, 2004

- Telemos, 2009

- nEUROn, 2012

Civilian[]

Dassault Falcon (Mystère) 20F-5

Dassault Falcon 2000

- Dassault M.D.320 Hirondelle

- Dassault Mystere 30 – 30/40 passenger regional jet not brought into production

- Mercure

- Dassault Communauté

- Falcon family

First flights[]

| Worldwide first | European first | French first | Company first |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1962: Prototype of the only vertical takeoff aircraft to have reached Mach 2, Dassault Mirage III V – Balzac V001 | 1955: First aircraft to reach Mach 2, Mirage III | 1949: First production jet fighter to be exported, MD 450 Ouragan | 1916: This first airplane product developed by Marcel Dassault was used on the Spad VII flown by French ace Georges Guynemer, Hélice Eclair |

| 1970: First business jet fitted with a wing designed using 3D computer modeling, Mystère-Falcon 10 | 1956: First production supersonic aircraft with afterburner, Super Mystère B2 | 1951: First aircraft to break the sound barrier in a dive, MD 452 Mystère II | 1918: First production aircraft by Marcel Dassault, SEA IV C2 – SEA IV |

| 1976: First business jet with a supercritical wing, Mystère-Falcon 50 | 1967: First ballistic missile, MD 620 | 1952: First production supersonic aircraft for the French Air Force, Mystère IV | 1932: First all-metal ambulance aircraft, MB 80–81 |

| 1979: First jet fighter with composite fin with built-in fuel tank, Mirage 4000 | 1968: "Swing wing" aircraft prototype whose G8 version reached Mach 2.34, Mirage G-4/G-8 | 1956: First French carrier-based jet fighter, Étendard IV | 1932: First commercial airliner, MB 120 |

| 1983: First jet fighter with automatic terrain following, Mirage 2000 N | 1971: First jointly-built jet airliner, Dassault Mercure 100 | 1959: First bomber for the French Strategic Air Force arm, Mirage IV | 1933: First bomber ordered and produced in large series, MB 200 |

| 1986: First technological demonstrator of a multipurpose jet fighter fulfilling the joint specifications of the French Air Force and Navy, Rafale A | 1978: First operational jet fighter with artificial stability, Mirage 2000 | 1974: First carrier-based jet fighter with modern weapons system, Dassault Super-Etendard | 1936: First production airliner, used by Air France, MB 220 |

| 1991: Single-seat development model of an omnirole jet fighter, Rafale C 01 | 2012: First European stealth UCAV (Unmanned Combat Air Vehicle) technology demonstrator, nEUROn | 1991: First multirole jet fighter, Mirage 2000-5 | 1938: First mass-production fighter, Bloch MB.150 |

| 1992: Single-seat development model of an omnirole jet fighter, Rafale M 01 | 2000: First jet fighter with avionics comprising a modular data processing suite, Mirage 2000-9 | 1939: First reconnaissance aircraft Aircraft piloted by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Bloch MB 174 | |

| 1993: Two-seat development model of an omnirole jet fighter, Rafale B 01 | 2012: First European combat aircraft in service equipped with an Active Electronically Scanned Array technology, Rafale F3.3 | 1947: First production aircraft after World War II, MD 315 Flamant | |

| 1993: First business jet built without a physical model, Falcon 2000 | 1963: First business jet, selected by Charles Lindbergh for Pan Am, Dassault Mystère-Falcon 20 | ||

| 2002: First business jet with enhanced avionics and intuitive cockpit, Falcon 900EX EASy | 1966 : First jet fighter with integrated digital weapons suite, Mirage F1 | ||

| 2005: First business jet equipped with a fully digital control system, Falcon 7X | 1973: First trainer aircraft built as a cooperative venture, Alpha Jet |

Space activities[]

| Aerospace vehicles | Pyrotechnics | Télemetry |

|---|---|---|

| 1962 : Two-solid-propellant-stage missile developed in the Company, MD620 | 1962 : Start of pyrotechnic business | 1992 : Dassault Aviation realizes telemetry ground system for Ariane 5 in Kourou, Ariane 5 |

| 1964 : First reusable launcher studies by Dassault Aviation, Two-stage aerospace transportation system | 1979 : First pyrotechnic equipment manufactured for a launcher, Ariane 1,2,3 & 4 | 2008 : National Centre for Space Studies renewed its confidence to Dassault aviation by granting it the contract of SCET Multi lanceurs development, SCET-M |

| 1983 : Dassault Aviation is deputy prime contractor in charge of aeronautic activities for Hermes space plane, Hermes | 1997 : Equipements pyrotechniques pour le lanceur Ariane 5, Ariane 5 | 2011 : First use of dedicated telemetry ground system with Ethernet network in Kourou, Soyuz |

| 1986 : Horizontal take-off and landing space reusable transportation system studied for National Centre for Space Studies, STAR-H | 2003 : Payload fairing separation system for one version of Atlas V americain launcher, Atlas V | 2012 : Adaptation of telemetry ground system in Kourou, Vega |

| 1997 : Modification of X-38 shapes for NASA, Crew Return Vehicle X-38 | 2008 : Development of a cutter to separate ATV freighter from Ariane 5, Ariane 5 | |

| 1998 : Study of a family of airbone reusable hypersonic vehicles for suborbital transport, Dassault VEHRA | 2012 : Development of vertical separation system for the payload fairing, Vega | |

| 2002 : Study of a manned suborbital vehicle carrying six people, VSH | ||

| 2005 : Participation to IXV atmospheric reentry demonstrator program, IXV | ||

| 2005 : Study of airbone micro launcher under Rafale to launch small payloads in low earth orbit, MLA |

Dassault Aviation Group Management[]

History of Chief Executive Officers[]

- Marcel Dassault: 1929–1950

- Auguste Le Révérend: 1950–1955

- Benno-Claude Vallières: 1955–1986

- Serge Dassault: 1986–2000

- Charles Edelstenne: 2000–2013

- Eric Trappier: since 9 January 2013[9]

Board of Directors[]

In 2012, the board of directors was composed of:

- Serge Dassault

- Charles Edelstenne

- Pierre de Bausset

- Nicole Dassault

- Olivier Dassault

- Alain Garcia

- Eric Trappier: replacing Philippe Hustache from 18 December 2012

- Denis Kessler

- Henri Proglio

Attendance fees are 22 000 euro / year per director with a double attendance fee for the chairman.

Management committee[]

- Loïk Segalen, chief operating officer since 9 January 2013

- Benoît Dussaugey, Executive Vice-President, International

- Benoît Berger, Executive Vice-President, Industrial Operations, Procurement and Purchasing

- Alain Bonny, Senior Vice-President, Military Customer Support Division

- Didier Gondoin, Executive Vice-President, Engineering

- Gérald Maria, Executive Vice-President, Total Quality

- Jean Sass, Executive Vice-President, Information Systems

- Olivier Villa, Senior Vice-President, Civil Aircraft

- Claude Defawe, Vice-President, National and Cooperative Military Sales

- Stéphane Fort, Senior Vice-President, Institutional Relations & Corporate Communications

- Jean-Jacques Cara, Senior Vice-President, Human Resources.

Dassault and the United States[]

From Marcel Dassault’s first look at a Wright airplane in 1909, which “brought aviation into my life, into my heart,” to today's Falcon business jets that are completed at Little Rock, Arkansas, Dassault Aviation has enjoyed a close, continuous relationship with the United States. These bonds have changed over time, reflecting the political and economic relations between the two countries.

A passion is born[]

Marcel Bloch, the founder of Dassault Aviation, was able to trace his passion for aviation to a very specific date, namely 18 October 1909. On that day, a Wright airplane piloted by the Comte de Lambert made the first flight over Paris, and even circled the Eiffel Tower. His life was changed forever. From that moment on, Marcel Bloch had a single burning ambition: to build airplanes.

The First World War gave him the opportunity to put his talents as a newly minted aeronautical engineer to the test. In 1916 he designed a new propeller, the “Éclair” (“lightning”), that would be used on Spad XIII fighters, especially those flown by the famous Lafayette Escadrille, a squadron manned by American volunteers, as well as by the country's leading WWI ace, Eddie Rickenbacker.

Conditions in France changed after the war, and Marcel Bloch left the aviation business for nearly a dozen years. But as he says in his autobiography “The Talisman”: “One day, or rather one evening, I was at Le Bourget airport, and I saw Lindbergh arrive in the Spirit of Saint Louis, after flying across the Atlantic. At that moment I understood that something had changed and that a real civil aviation industry was about to be born. Just as the Wright's airplane had awakened my interest in aviation, the Spirit of Saint Louis brought me back to it.”[10]

Marcel Bloch founded a new company in 1929, and within six years it had become the second leading airplane manufacturer in France. After the German invasion of France in World War II, he took refuge in Bordeaux. At the time, he thought about moving his family to the United States, where he knew that he would receive a warm welcome. But because of his patriotism he stayed in France. Returning from Buchenwald in 1945, he changed his name to Marcel Dassault. The new name came from “char d’assaut” (“battle tank”) the nom de guerre of a brother who was a resistance fighter. He added the letter "L" to “d’assaut” in honor of an airplane wing, in French the "aile" (pronounced “L”). At the age of 53, he restarted his career as a major aircraft manufacturer, a career that would culminate in 1976 with the highest distinction for an aeronautical engineer, the Daniel Guggenheim Medal, awarded by Malcolm S. Harned, head of Cessna at the time.[11]

In 1959 Marcel Dassault moved his company's headquarters to the western Paris suburb of Vaucresson. He purchased a building that had initially been built for the Universal Exposition of 1937 – and which is a carbon copy of Mount Vernon, George Washington's estate in Virginia along the banks of the Potomac!

Military Aviation[]

Following the Second World War, France and the United States enjoyed a very close relationship on military matters, in particular via NATO.

American test pilot Marion Davis was the first to break the sound barrier in France, in 1952, flying a Dassault Mystère II. A number of American delegations came to visit Dassault's facilities, including prestigious visitors such as General Richard Boyd and Chuck Yeager. These contacts would lead to an order for 185 MD 450 Ouragan fighters in 1950, then 225 Mystère IV fighters in 1953, deployed by the French air force on behalf of NATO, and financed by an American aid program for Western Europe (Mutual Defense Assistance Program).

Marcel Dassault kept a close watch on American technical progress through the trade press. Engineers at Dassault began to get acquainted with their counterparts on the other side of the Atlantic. For instance, in 1955 they were in contact with Edward Heinemann of Douglas, creator of the Skyray and Skyhawk, concerning delta wing designs. Dassault's planes drew inspiration from various techniques developed in the U.S., such as the swept wings of the Mystère (F-86), the delta wing, wasp waist and air inlet cones on the Mirage III (F-102 and F-104), the variable geometry wing on the Mirage G (F-111), and even the supercritical wing on the Falcon 50 (an airfoil developed by NACA).

Dassault's longest-standing relationship with a major American plane-maker is with Boeing. In the early 1960s, there was the Mirage III W project (“W” for Wichita, the city in Kansas where Boeing had some of its plants) and work on vertical takeoff models; then the Mirage F 1 in the early 1970s, and from 1991 to 1995 the delivery of about 2,500 servocontrols for the rotors on CH-47 Chinook helicopters. There was also a joint study of advanced fighter aircraft during the maturation phase of the JAST (now the JSF) from 1994 to 1996, etc.

The vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) Mirage is an excellent example.

Boeing wanted to enter the small fighter market by teaming up with the French manufacturer. On 23 December 1961, the two companies signed technical collaboration and licensing agreements, especially for the vertical takeoff stabilization devices and Dassault control systems. Once these agreements were accepted by the two governments, the first objective was a joint proposal to NATO for a vertical takeoff fighter. In early 1963, the U.S. air force considered the purchase of three Mirage III V planes, identical to the twin-seat Mirage III V 03 project, for testing. Boeing was to reassemble the planes in the United States and set up test facilities. The U.S. Air Force planned to acquire two aircraft in May 1964, but was unable to follow through on this plan. Despite this, there were very fruitful exchanges of engineers between Dassault and Boeing. As early as 16 March 1964, Robert Schroers, specialist in Boeing 727 certification, worked on the American certification of the Mystère 20, while Jacques Alberto contributed his expertise in VTOL aircraft to Boeing.

Dassault also worked closely with two other American plane-makers on specific projects: LTV (Ling-Temco-Vought) on the Mirage G variable geometry aircraft (1968–69) and Lockheed on the Alpha Jet VTX trainer for the U.S. Navy (1978).

Marcel Dassault always took a keen interest in American jet engines, and in fact he would have liked to power his aircraft with these engines. Pratt & Whitney turbojets were fitted to Mirage III T, III V, F-2 and G prototypes in the 1960s. But with France leaving NATO's integrated military organization and General de Gaulle fostering a policy of weapon independence, the national champion Snecma became the Mirage engine supplier.

Dassault's success intrigued observers in the United States. In 1973 the U.S. Air Force ordered a study of Dassault by the Rand Corporation,[12] a California based think tank. Rand said that Dassault “was generally held to be one of the most efficient aircraft development and production firms in the western world.”

The study was designed to assess Dassault and identify certain qualities that could be adapted for use in the United States. In conclusion, the report stated: “It seems feasible to adopt several of the basic Dassault policies in the development of aircraft in the United States, with potentially great advantages in cost and with long-term benefits for stability of the aircraft industry in the United States. Such adoption would undoubtedly cause major changes in the structures of the American aerospace complex, government and civil."

In the early 1990s, the carrier-borne Rafale M fighter was successfully tested in the United States, including evaluations of its advanced landing gear system, with catapult and deck landing tests on runways at Patuxent River and Lakehurst.

For many years military aircraft were the core business at Dassault, and established the company’s global reputation. But today, the most successful area of collaboration between Dassault and the United States is undoubtedly business aviation.

Business aviation[]

The business aviation market was still nascent in the early 1960s. Most major corporations still hesitated to deploy these aircraft, which had not yet proven their cost-effectiveness. The United States was by far the dominant market, and without a breakthrough in this market, no new aircraft had the slightest chance of turning a profit.

Dassault’s Export department, headed by Serge Dassault, launched a marketing campaign that primarily targeted the United States, which harbored the most promising market. Building on relations established since their agreements on military aircraft in October 1961, Dassault and Boeing sought to reach an accord on smaller civilian aircraft, with 4–6, 21 or 40 seats. Dassault presented its plans for the Mystère 20 business twinjet to Boeing, but the discussions were ultimately unsuccessful, as Boeing finally decided not to invest in the business aviation segment.

In October 1962 Serge Dassault traveled to the United States to take a closer look at the market potential for the Mystère 20. He was convinced that the aircraft met the needs of the American market and insisted that the program be launched quickly.

At about that time, Pan American World Airways was thinking of diversifying its business by creating a department for the distribution of business aircraft. Several members of corporate management, including Charles Lindbergh, came to Mérignac (the main plant near Bordeaux) to see the prototype before its maiden flight. They were immediately taken with this new aircraft, and started negotiations, culminating on 2 August 1963, with a firm order for 40 of these aircraft, powered by General Electric CF 700 turbofan engines, along with options on 120 more. This exceptional contract launched the Mystère 20 bizjet on the international market, and also allowed Dassault to diversify its business away from its traditional exclusively military stance. The Fan Jet Falcon, as it was named in the United States, hit the American market in the summer of 1965. It quickly acquired a solid reputation for comfort and safety under the Falcon 20 designation – the first model in a large family that now has 1,800 aircraft in service worldwide (2007).[13]

However, nearly all Falcons in the United States were bought as single units, and they were operating thousands of kilometers away from the manufacturer, all of which complicated support services. In November 1972 Dassault created a French-American company in charge of sales and aftersales services. Based in Teterboro, New Jersey, this company was a joint venture between Dassault and Pan Am, in charge of Falcon business jet sales in North America. Falcon Jet Corporation was responsible for new plane sales and MRO services throughout the Americas, as well as in Asian countries on the Pacific rim (Western hemisphere). In 1974 Falcon Jet Corp. acquired Little Rock Airmotive Company, an Arkansas company specialized in business aircraft cabin outfitting. Starting in April 1975, the Falcons built in Dassault's facilities in Bordeaux-Mérignac, and sold to customers in the West, were flown to Little Rock for interiors, livery and instruments, before being delivered. This plant also handled maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) services for Falcon jets operating in this zone. The company grew rapidly, taking responsibility for the sale and support of nearly two-thirds of Falcon production. Dassault bought out Pan Am's share in 1980, turning Falcon Jet Corporation into a wholly owned subsidiary. On 1 January 1995, Falcon Jet Corporation became Dassault Falcon Jet, the American subsidiary of Dassault Aviation.

Two major contracts would establish Dassault's presence in the United States once and for all.

- In 1971 Frederick W. Smith studied the possibility of delivering packages overnight by air, with final delivery to customers by a fleet of small trucks. After comparing several different aircraft, he bought 33 Falcon 20s and in 1972 created Federal Express Corporation, the only airline in the world with an all-French fleet. FedEx's Falcon 20s were fitted with an extra cargo door and a special floor 20 feet long – making this the world's first Minifreighter Cargo Jet. Service kicked off on 17 April 1973, between 25 cities. Growth was so outstanding that in 1982 Federal Express replaced this original fleet with larger Boeing 727 and McDonnell Douglas DC-10 aircraft.

- On 5 January 1977, the United States Coast Guard was authorized to order 41 airplanes meeting the MRS (Medium Range Surveillance) program requirements. It chose the Falcon Jet Corporation HU 25A Guardian, a derivative of the Mystère-Falcon 20 F, powered by Garrett ATF 3–6 engines. All 41 aircraft were delivered from 1981 to 1983. Subsequently, several of these models were outfitted with special equipment for either maritime pollution monitoring (HU 25B) or illegal drug interdiction (HU 25C).

Dassault worked closely with its American customers before launching any of these special models.

In 1969 Garrett Corporation launched a new, smaller jet engine, the TRE 731, which matched the power needs of the Falcon 10. On 31 December 1969, a year before first flight of the new aircraft, Pan Am placed an order for 40 Falcon 10s, along with 120 options.

Having added a smaller aircraft to its range, Dassault now designed a new business jet that was larger than the Falcon 20. This new aircraft had to meet customer demand for a significant increase in range, allowing it to make non-stop flights across the United States, or across the North Atlantic. In 1973, this gave rise to the Falcon 50 – the first aircraft in the Falcon family with transoceanic range. Prior to the Falcon 50, no business jet offered transatlantic range plus compliance with public transport standards.

However, in the early 1980s the American business jet market experienced a sharp downturn, with only the high-end segment proving resilient. Customers wanted widebody bizjets – so Dassault started design studies to meet this new demand, resulting in the Falcon 900.

Subsequently, Falcon Jet Corporation launched a market survey of its North American customers in 1987 and 1988. The most important factors cited by customers were: the cabin (height, width and length), then range, speed, operating cost and runway length. These studies resulted in the design of the Falcon 2000, primarily intended for the premium “coast to coast” market in the United States.

By 2012 business aviation was a core business at Dassault Aviation, accounting for 86% of orders and 71% of sales. The United States represents 39% of the international Falcon market. And the Little Rock plant, with nearly 1,700 people, is one of the largest employers in the state of Arkansas.

See also[]

- Dassault Group

- Dassault Falcon

- Dassault Rafale

- Mirage 2000

- nEUROn

References[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 GAMA : General Aviation Airplane Shipment Report – 2012 Year end, 9 May 2013

- ↑ "Dassault Names Eric Trappier as Chief to Succeed Edelstenne". Bloomberg Businessweek. http://www.businessweek.com/news/2012-12-18/dassault-aviation-names-trappier-as-chief-to-succeed-edelstenne. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ↑ "History of Groupe Dassault Aviation S". http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/groupe-dassault-aviation-sa-history/. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ↑ Dassault Aviation History, 1916 to this day: During the War. Accessed 5 January 2006.

- ↑ Claude Carlier, "Marcel Dassault, la légende du siècle", Page 91, Éditions Perrin, 1992.

- ↑ Dassault Aviation History, 1916 to this day: The company's successive reorganizations. Accessed 5 January 2006.

- ↑ "History of Dassault Systems". http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/dassault-syst%C3%A8mes-s-a-history/. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ↑ Dassault Aviation 2010 Annual Report.

- ↑ "Eric Trappier Named New Head of Dassault Aviation". Aviation Office. http://dev.aviation-office.com/office-new/aviation-accident-reports/1560504.html. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ↑ Dassault Stories.. Luc Berger, Editions Timée.

- ↑ "Marcel Dassault Award citation: For notable achievement in development, production and marketing of many types of aircraft of high performance and outstanding leadership in world aviation.". Daniel Guggenheim Medal. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guggenheim_Medal#cite_note-50. Retrieved 1976-01-01.

- ↑ A Dassault Dossier: Aircraft Acquisition in France. Robert Perry R-1148-PR.

- ↑ Dassault Falcon Story.. Luc Berger, Editions Le Cherche-Midi.

- Dassault Aviation History, 1916 to this day. Accessed 5 Jan 2006.

Further reading[]

- Claude Carlier and Luc Berger, Dassault, 1945 – 1995, 50 years of aeronautical adventure, Editions du Chêne, 1996.

- Claude Carlier, Marcel Dassault, La légende d'un siècle, éditions Perrin, 1992 – revised in May 2002.

- Claude Carlier, Serge Dassault, 50 ans de défis, éditions Perrin, August 2002.

- Luc Berger, Dassault Stories, Editions Timée, 2006.

- Luc Berger, Dassault Falcon story, Editions Le Cherche-Midi, February 2004.

- Henri Deplante, À la conquête du ciel, éditions Édisud, January 1985

- Emmanuel Chadeau, L'Industrie aéronautique française, 1900–1950. De Blériot à Dassault, éditions Fayard, 1987.

- Emmanuel Chadeau, L'Économie du risque, Paris, éd. O. Orban, 1988.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dassault Aviation. |

The original article can be found at Dassault Aviation and the edit history here.