DAR Constitution Hall, Washington, DC

The organization Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) is a lineage-based membership service organization for women who are directly descended from a person involved in United States' independence.[1] A non-profit group, they work to promote historic preservation, education and patriotism. The DAR has chapters in all 50 U.S. states as well as in the District of Columbia. DAR chapters have been founded in Australia, Austria, the Bahamas, Bermuda, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Spain, and the United Kingdom. As of 2012, over 850,000 women have been able to trace their lineage to join this organization. Although it is referred to as the DAR, the official name of this organization is the National Society of Daughters of the American Revolution (NSDAR). National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution patriotic society organized October 11, 1890, and chartered by Congress December 2, 1896. Membership is limited to direct lineal descendants of soldiers or others of the Revolutionary period who aided the cause of independence; applicants must have reached 18 years of age and must be “personally acceptable” to the society. In the late 20th century the society's membership totaled approximately 180,000, with some 3,000 local chapters throughout the United States and in several other countries.[2] In 1889 the centennial of President George Washington's inauguration was celebrated, and Americans looked for additional ways to recognize their past. Out of the renewed interest in United States history, numerous patriotic and preservation societies were founded. One of the society's four co-founders was Eugenia Washington, a great-grandneice of George Washington. The First Lady, Caroline Lavina Scott Harrison, wife of the United States President Benjamin Harrison, lent her prestige to the founding of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (NSDAR). She served as its first President General. She had initiated a renovation of the White House to update its infrastructure and was interested in historic preservation. She helped establish the goals of NSDAR. Four Washington, DC women founded the first chapter on October 11, 1890. The National Society of the DAR was incorporated by congressional charter in 1896.

DAR's motto is "God, Home, and Country."

In this same period, such organizations as the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR), the Colonial Dames of America, the Mary Washington Memorial Society, Preservation of the Virginia Antiquities, United Daughters of the Confederacy, and Sons of Confederate Veterans were also founded. This was in addition to numerous fraternal and civic organizations.

Historic programs[]

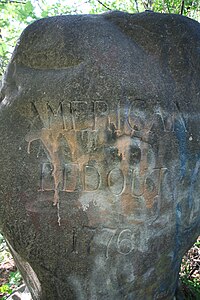

The DAR chapters raised funds to initiate a number of historic preservation and patriotic endeavors. They began a practice of installing small markers at the graves of Revolutionary War veterans to indicate their service, and adding small flags at their gravesites on Memorial Day.

Other activities included commissioning and installing monuments to battles and other sites related to the War. The DAR women's contributions as well as those of soldiers. For instance, they installed a monument at the site of a spring where Polly Hawkins Craig and other women got water to use against flaming arrows, in the defense of Bryan Station (present-day Lexington, Kentucky).

In addition to installing markers and monuments, DAR chapters have purchased, preserved and operated historic houses and other sites associated with the war. See "DAR Historic Sites and Database" for a map and database of DAR sites.

Current membership and programs[]

Eligibility[]

Membership in the DAR today is open to all women, regardless of race or religion, who can prove lineal bloodline descent from an ancestor who aided in achieving United States independence.[1] The National Society of DAR is the final arbiter of the acceptability of the documentation of all applications for membership.

Qualifying participation in achieving independence includes the following:

- Signatories of the United States Declaration of Independence;

- Military veterans of the American Revolutionary War, including State navies and militias, local militias, privateers, and French or Spanish soldiers and sailors who fought in the American theater of war;

- Civil servants of provisional or State governments, Continental Congress and State conventions and assemblies;

- Signers of Oath of Allegiance or Oath of Fidelity and Support;

- Participants in the Boston Tea Party;

- Prisoners of war, refugees, and defenders of fortresses and frontiers; doctors and nurses who aided Revolutionary casualties; ministers; petitioners; and

- Others who gave material or patriotic support to the Revolutionary cause.[1]

Educational outreach[]

- DAR schools:

The DAR contributes more than $1 million annually to support six schools that provide for a variety of special student needs.[3] Supported schools include:

- Kate Duncan Smith DAR School, Grant, Alabama

- Tamassee DAR School, Tamassee, South Carolina

- Crossnore School, Crossnore, North Carolina

- Hillside School, Marlborough, Massachusetts

- Hindman Settlement School, Hindman, Kentucky

- Berry College, Mount Berry, Georgia

- Scholarships for American Indian youth:

In addition, the DAR provides $70,000 to $100,000 in scholarships and funds to American Indian youth at Chemawa Indian School, Salem, Oregon; Bacone College, Muskogee, Oklahoma; and the Indian Youth of America Summer Camp Program.[4]

American History Essay contest[]

Each year, the DAR conducts a national American history essay contest among students in grades 5 through 8. A different topic is selected each year. Essays are judged "for historical accuracy, adherence to topic, organization of materials, interest, originality, spelling, grammar, punctuation, and neatness." The contest is conducted locally by the DAR chapters. Chapter winners compete against each other by region and nationally; national winners receive a monetary award.[5]

Scholarships[]

The DAR awards $150,000 per year in scholarships to high school graduates, and music, law, nursing, and medical school students. Only two of the 20 scholarships offered are restricted to DAR members or their descendants.[6]

Literacy promotion[]

In 1989, the DAR established the NSDAR Literacy Promotion Committee, which coordinates the efforts of DAR volunteers to promote child and adult literacy. Volunteers teach English, tutor reading, prepare students for GED examinations, raise funds for literacy programs, and participate in many other ways.[7]

Exhibits and library at DAR Headquarters[]

The DAR maintains an extensive genealogical library at its headquarters in Washington, DC and provides guides for individuals doing family research. Its bookstore presents the latest scholarship on United States and women's history.

Temporary exhibits in the galleries have featured women's arts and crafts, including items from the DAR's valuable quilt and embroidery collections. Exhibit curators provide a social and historical context for girls' and women's arts in such exhibits, for instance, explaining practices of mourning reflected in certain kinds of embroidery samplers, as well as ideals expressed about the new republic. Permanent exhibits include American furniture, silver and furnishings.

Racial history[]

Performers at Constitution Hall[]

Although the DAR now forbids discrimination in membership based on race or creed, some members earlier advocated for segregation and discrimination. In 1932, Washington, D.C. still had segregated facilities under laws established by a Southern-dominated Congress, which then administered the city. The DAR adopted a rule excluding African-American musicians from performing at Constitution Hall. This decision had followed complaints by some members against "mixed seating," as both blacks and whites were attracted to concerts of black artists.[8]

In 1936, Sol Hurok, the manager since 1935 of Marian Anderson, an African-American contralto, tried to book her at the DAR Constitution Hall. Owing to the "white performers only" policy, the DAR refused the booking. As the issue became public, Anderson performed at a Washington-area black high school. The First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt invited her to the White House to perform especially for her and President Roosevelt. During this time, Anderson came under considerable pressure from the NAACP not to perform for segregated audiences.[9]

In 1939, Hurok, along with the NAACP and Howard University, petitioned the DAR to make an exception to the "white performers only" policy for a new booking of his renowned singer, which the organization declined. Hurok tried to find a local high school for the performance, but the only suitable venue was an auditorium at a white high school (the public schools were segregated). The school board refused to allow Anderson to perform there.[9]

In response, Eleanor Roosevelt immediately resigned her membership in the DAR.[8] The organization later apologized to Anderson and welcomed her to Constitution Hall on a number of occasions, starting in 1942 with a benefit concert for war relief during World War II.[10] But, the DAR did not officially reverse its "white performers only" policy until 1952.[11]

In 1945, the African-American jazz singer Hazel Scott (then the wife of Democratic congressmen Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.) was excluded from performing at Constitution Hall. In October 1945, the first lady Bess Truman was invited to a tea by the DAR at the locale. Truman accepted without realizing there would be a controversy. Congressman Powell protested and asked Truman not to attend the tea. She chose to go, but said that she opposed discrimination (as did her husband). Letters of protest sent to the White House asked Bess Truman to resign from the DAR, but she declined to do so. Other letters supported her attendance at the tea.[12][13]

In 1964, Anderson chose Constitution Hall as the place to launch her farewell American tour.[14]

On January 27, 2005, the DAR co-hosted with the U.S. Postal Service the first "day of issue" dedication ceremony of the Marian Anderson commemorative stamp, at which Anderson's family was honored.[15]

First African-American member of DAR[]

In October 1977, Karen Batchelor Farmer (now Karen Batchelor) of Detroit, Michigan was admitted as the first known African-American member of the DAR.[16] Batchelor started her genealogical research in 1976 as a young mother who wanted to commemorate the American bicentennial year in a way that had special meaning for her family. Within 26 months, she had traced her family history back to the American Revolution—a completely unexpected result. Batchelor traced her ancestry to a patriot, William Hood, who served in the colonial militia in Pennsylvania during the Revolution in the defense of Fort Freeland.[17]

With the help of the late James Dent Walker, head of Genealogical Services at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., Batchelor was contacted by the Ezra Parker Chapter in Royal Oak, Michigan, who invited her to join their chapter; she officially became DAR member #623,128. In December 1977, Batchelor's admission as the first known African-American member of DAR sparked international interest after it was featured in a story on page one of the New York Times.[18] She was invited to appear on Good Morning America, where she was interviewed by the regular guest host John Lindsay, former mayor of New York.

Batchelor co-founded the Fred Hart Williams Genealogical Society in 1979, an organization in Detroit for African-American family research. She continues to research her own family history and inspire others to do the same.

Ferguson controversy[]

In March 1984, a controversy arose when Lena Lorraine Santos Ferguson said she had been denied membership in a Washington, D.C. chapter of the DAR because she was black.[19] The reporter Ronald Kessler quoted Ferguson's two white sponsors, Margaret M. Johnston and Elizabeth E. Thompson, as saying that although Ferguson met the lineage requirements and could trace her ancestry to Jonah Gay, fellow DAR members told them that Ferguson was not wanted because she was black.[19]

Sarah M. King, the President General of the DAR, said that the DAR's chapters have autonomy in determining members. Asked if she thought this acceptable, she said, "If you give a dinner party, and someone insisted on coming and you didn't want them, what would you do?" King continued,

"Being black is not the only reason why some people have not been accepted into chapters. There are other reasons: divorce, spite, neighbors' dislike. I would say being black is very far down the line ... There are a lot of people who are troublemakers. You wouldn't want them in there because they could cause some problems."[19]

After her comments were reported, the Council of the District of Columbia|D.C. City Council threatened to revoke the DAR's real estate tax exemption. King said that Ferguson should have been admitted, and her application to join the DAR was handled "inappropriately". Representing Ferguson free of charge, lawyers from the Washington law firm of Hogan & Hartson began working with King to develop positive ways to ensure that blacks would not be discriminated against when applying for membership. The DAR changed its bylaws to bar discrimination "on the basis of race or creed". King announced a resolution to recognize "the heroic contributions of black patriots in the American Revolution".[19]

As a result of the Washington Post story, Ferguson, a retired school secretary, was admitted to the DAR chapter. "I wanted to honor my mother and father as well as my black and white heritage," Ferguson said after being admitted. "And I want to encourage other black women to embrace their own rich history, because we're all Americans."[19] She became chairman and founder of the D.C. DAR Scholarship Committee. She died in March 2004 at the age of 75.

Becoming more inclusive[]

As noted above in the requirements section, the DAR has recognized that a wide variety of people contributed to the war effort, and has broadened its guidelines to reflect that. As an example of such changes, in 2007 the DAR posthumously honored Mary Hemings Bell, a former slave of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello, as a "Patriot of the Revolution." During the war, Hemings and other household slaves had been taken by Jefferson to Richmond to work for him after he was elected as governor of Virginia. When the British invaded the city, they took Hemings and the other slaves at the governor's house as prisoner. The American government officials had escaped to Monticello and Charlottesville. Hemings and the other slaves were later released. Since Hemings Bell has been honored as a Patriot, all of her female descendants qualify for membership in the DAR.[20]

After the war, Hemings gained informal freedom when her common-law husband, Thomas Bell, a white merchant of Charlottesville, purchased her and their two mixed-race children from Jefferson. She was forced to leave her two older children, Joseph Fossett and Betsy Hemmings (as she spelled it), enslaved at Monticello. After Bell's death, Mary and their two children inherited his estate. She kept in touch with her large extended Hemings family, still enslaved at Monticello, and aided her children there. When Jefferson's slaves were sold after his death in 1826 to settle his debts, Mary Hemings Bell was able to purchase family members to help keep families intact.[21]

First African-American charter chapter[]

In June 2012, Wilhelmena Rhodes Kelly and Dr. Olivia Cousins became the charter members of a chapter with more than one African-American member, in Queens, New York.[22] Five of the 13 charter members are African American. Kelly was installed as the Charter Regent and Dr. Cousins as a chapter officer. Two of Dr. Cousins' sisters, Collette Cousins, who lives in Durham, North Carolina, and Michelle Wherry, who lives in Lewis Center, Ohio, have pledged to travel to Queens for the monthly chapter meetings.

Notable DAR members[]

- Past members

Daughters of the American Revolution monument to the Battle of Fort Washington, erected in 1910. The approach deck of the George Washington Bridge, New York City was built above it.

- Susan B. Anthony, American suffragist[23]

- Clara Barton, American Red Cross founder[23]

- Estelle Skidmore Doremus, supporter of the New York Philharmonic

- Lillian Gish, American actress[23]

- Grandma Moses, American folk artist[23]

- Ginger Rogers, American actress and dancer[23]

- Caroline Scott Harrison, former First Lady of the United States[23]

- Infanta Eulalia of Spain, Spanish princess and author[24]

- Mary Baker Eddy, founder of Christian Science church

- Living members

- Suzanne Bishopric, treasurer of the United Nations

- Dr. Betsy Boze, American academic—Chief Executive Officer and Dean, Kent State University Stark[25]

- Laura Welch Bush, former First Lady of the United States

- Rosalynn Smith Carter, former First Lady of the United States, politician, political and social activist

- Elizabeth Hanford Dole, former U.S. Senator from North Carolina, former Transportation secretary, Labor secretary, American Red Cross president, Federal Trade Commissioner, Presidential candidate, and Presidential advisor

- Janet Reno, former Attorney General of the United States

- Bo Derek, actress, former model, and conservative political activist

- Phyllis Schlafly, conservative political activist and writer

- Honorary members

- Mary Hemings Bell, slave of Thomas Jefferson, was posthumously honored in 2007, as she was held as a British prisoner-of-war during the Revolution.[20] All her female descendants are eligible for the DAR.

References in popular culture[]

- Grant Wood used the DAR as the subject for his 1932 painting Daughters of Revolution. At that time, he thought the group was characterized by elitism and class distinction.

- In the musical The Music Man, the lyrics to "Wells Fargo Wagon" include "The D.A.R. have sent a cannon for the courthouse square."

- In Sinclair Lewis's 1935 novel It Can't Happen Here, the DAR is generally portrayed as "composed of females who spend one half of their waking hours boasting of being descended from the seditious American colonists of 1776, and the other and more ardent half in attacking all contemporaries who believe in precisely the principles for which those ancestors struggled."

- In chapter 39 of Thomas Wolfe's novel You Can't Go Home Again (1940), the German character Franz Heilig lumps the DAR in with salon Communists, the Chamber of Commerce, and the American Legion. He said all were like the Nazi Party in repressing dissent.

- Abbey Bartlet, the first lady in the fictional television drama The West Wing, was a member of the DAR. (4×18—Privateers)

- A running joke in the movie The American President (1995) is that President Shepard (Michael Douglas) accidentally skipped a paragraph during a speech to the DAR, causing minor embarrassment to the White House.

- The fictional characters Emily and Rory Gilmore of the TV series Gilmore Girls are members of the DAR.

- The fictional character Lovey Howell of Gilligan's Island is a member of the DAR.

- The fictional character Margaret Houlihan of M*A*S*H is blackballed in the 1950s by her mother-in-law from being admitted as a member of the DAR.

- In the play The Glass Menagerie by Tennessee Williams, the character Amanda, who refers to her cultivate Southern past, is asked by her daughter if she attended the DAR meeting.

- At the end of Stan Freberg Presents The United States of America Volume One The Early Years, a member of the DAR (played by June Foray) attempts to lodge a protest about the recording.

- Phil Ochs's song "Love Me, I'm a Liberal" mentions "put[ting] down the old D.A.R, D.A.R.: that's the Dykes of the American Revolution."

- The Black Crowes have a song, "Goodbye Daughters of the Revolution".

- Walter Matthau's final line in Grumpy Old Men is, "The Daughters of the American Revolution are having a dance at the VFW Hall."

- In Pan Am, a historical TV series, the mother of the characters Kate and Laura Cameron, who are both stewardesses, belongs to the DAR.

- The band Jets to Brazil has the lyric "daughters of the revolution you're freezing in your furs" in the song "Lemon Yellow Black".

- The Chad Mitchell Trio song, "The John Birch Society," features the line: "Do you want Mrs. Khrushchev in there with the DAR?"

- In the novel The Help, Skeeter's mother, Charlotte, reveals to her that she fired Constantine while the DAR chapter was at their house.

See also[]

- Children of the American Revolution (C.A.R.)

- Sons of the American Revolution (SAR)

- Sons of Confederate Veterans

- Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War

- United Daughters of the Confederacy

References[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 preserving historical properties and artifacts and promoting patriotism within their communities. "Become a Member". Daughters of the American Revolution. http://www.dar.org/natsociety/content.cfm?ID=145&hd=n&Fs, preserving historical properties and artifacts and promoting patriotism within their communities..

- ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution. (2013). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from http://library.eb.com/eb/article-9029443

- ↑ "DAR Supported Schools". DAR. http://www.dar.org/natsociety/edoutrech.cfm. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- ↑ "Work of the Society: DAR Schools". DAR. http://dar.org/natsociety/worksociety.cfm. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ "American History Essay". DAR. http://www.dar.org/natsociety/content.cfm?id=319&fo=y&hd=n. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- ↑ "Scholarships". DAR. http://www.dar.org/natsociety/edout_scholar.cfm. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- ↑ "Literacy Promotion". DAR. http://www.dar.org/natsociety/content.cfm?id=265&fo=y&hd=n. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Exhibit: Eleanor Roosevelt Letter". NARA. 1939-02-26. http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/american_originals/eleanor.html. Retrieved 2006-10-08.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Marian Anderson at the MET: The 50th Anniversary, Early Career". The Metropolitan Opera Guild, Inc.. 2005. http://www.marian-anderson.org/early_career.htm. Retrieved 2006-10-08.

- ↑ "D.A.R. NOW INVITES MARIAN ANDERSON; Singer, Barred From Capital Hall in 1939, Is Asked to Give First of War Aid Concerts". New York Times. 1942-09-30. pp. Obits. pp. 25. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F60A14FD385D167B93C2AA1782D85F468485F9. Retrieved 2006-10-08.

- ↑ Kennedy Center, "Biography of Marian Anderson".

- ↑ "D.A.R. Refuses Auditorium to Hazel Scott; Constitution Hall for 'White Artists Only'", New York Times, 12 October 1945, accessed 5 August 2012

- ↑ Sale, Sara L. Bess Wallace Truman: Harry's White House "Boss", University Press of Kansas, 2010. ISBN 9780700617418

- ↑ "Marian Anderson at the MET: The 50th Anniversary, Late Life". The Metropolitan Opera Guild, Inc.. 2005. http://www.marian-anderson.org/late_life.htm. Retrieved 2006-10-08.

- ↑ "Legendary Singer Marian Anderson Returns to Constitution Hall On U.S. Postage Stamp". United States Postal Service. 2005-01-04. http://www.usps.com/communications/news/stamps/2005/sr05_001.htm. Retrieved 2006-10-08.

- ↑ "Karen Farmer", American Libraries 39 (February 1978), p. 70; Negro Almanac, pp. 73,1431; Who's Who among Africans, 14th ed., p. 405.

- ↑ Northumberland County in the American Revolution, 1976, pp. 156, 171.

- ↑ Stevens, William K. (1977-12-28). "A Detroit Black Woman's Roots Lead to a Welcome in the D.A.R.; Black Woman's Roots Lead to a Welcome in D.A.R". The New York Times. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F40B11FA3D5A167493CAAB1789D95F438785F9.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Kessler, Ronald (1984-03-12). "Black Unable to Join Local DAR". Washington Post. p. 1. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/washingtonpost_historical/access/170896782.html?dids=170896782:170896782&FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT&date=MAR+12%2C+1984&author=By+Ronald+Kessler+Washington+Post+Staff+Writer&pub=The+Washington+Post&desc=Black+Unable+to+Join+Local+DAR&pqatl=google.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 American Spirit Magazine, Daughters of the American Revolution, January–February 2009, p. 4

- ↑ Annette Gordon-Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family, New York: W. W. Norton & Co., pp. 410, 484

- ↑ Maslin Nir, Sarah (2012-07-03). "For Daughters of the American Revolution, a New Chapter". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/04/nyregion/for-daughters-of-the-american-revolution-more-black-members.html?emc=eta1. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 "Dazzling Daughters, 1890–2004". Americana Collection exhibit. DAR. http://www.dar.org/americana/currexhib.cfm. Retrieved 2006-10-08.

- ↑ Hunter, Ann Arnold, A Century of Service: The Story of the DAR, p. 63

- ↑ Meet Our Deans

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Archives and Records Administration website http://www.archives.gov/.

Further reading[]

- Bailey, Diana L. American Treasure: The Enduring Spirit of the DAR. 2007. Walsworth Publishing Company.

- Hunter, Ann Arnold. A Century of Service: The Story of the DAR. 1991, Washington, DC. National Society Daughters of the American Revolution.

- Strayer, Martha. The D.A.R.: An Informal History. 1958, Washington, DC. Public Affairs Press. (critically reviewed by Gilbert Steiner as covering personalities but not politics, Review, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, v.320, "Highway Safety and Traffic Control" (Nov. 1958), pp. 148–49.)

External links[]

- National Society of Daughters of the American Revolution, Official website

- "DAR Historic Sites and Database", includes national map

- Daughters of the American Revolution at DMOZ

- Daughters of the American Revolution (David Reese Chapter) Collection (MUM00098), University of Mississippi

- "Daughters of the American Revolution Library", FamilySearch Research Wiki, for genealogists

- Madonna of the Trail Monument, Website

- "Daughters of the American Revolution", image by Grant Wood

- [1] James Madison University's Massanutten Chapter, National Society of Daughters of the American Revolution Collection, 1885-2005

The original article can be found at Daughters of the American Revolution and the edit history here.