EO-1 Satellite Image of Enewetak Atoll. The crater formed by the Ivy Mike nuclear test can be seen on the northeast cape of the atoll. | |

|

Enewetak Atoll (Marshall islands) | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | North Pacific |

| Coordinates | 11°30′N 162°20′E / 11.5°N 162.333°ECoordinates: 11°30′N 162°20′E / 11.5°N 162.333°E |

| Archipelago | Ralik |

| Total islands | 40 |

| Highest elevation | 5 m (16 ft) |

| Country | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 853 (as of 1998) |

| Ethnic groups | Marshallese |

Map of Enewetak Atoll

Aerial view of Enewetak and Parry

Enewetak Atoll (or Eniwetok Atoll, sometimes also spelled Eniewetok; Marshallese language: Ānewetak, [æ̯ænʲee̯ɔ̯ɔ͡ɛɛ̯dˠɑk], or Āne-wātak, [æ̯ænʲee̯-ɒ̯ɒ͡ææ̯dˠɑk][1]) is a large coral atoll of 40 islands in the Pacific Ocean, and with its 850 people forms a legislative district of the Ralik Chain of the Marshall Islands. Its land area totals less than 5.85 square kilometres (2.26 sq mi), not higher than 5 metres and surrounding a deep central lagoon, 80 kilometres (50 mi) in circumference. It is the second-westernmost atoll of the Ralik Chain, and is located 305 kilometres (190 mi) west from Bikini Atoll. The U.S. government referred to the atoll as "Eniwetok" until 1974, when it changed its official spelling to "Enewetak" (along with many other Marshall Islands place names, to more properly reflect their pronunciation by the Marshall Islanders[2]). In 1977–1980, a concrete dome was built on Runit Island to deposit radioactive soil and debris.[3]

Geography

Enewetak Atoll formed atop a seamount. The seamount was formed in the late Cretaceous (about 75.8 million years ago).[4] This seamount is now about 4,600 feet (1,400 m) below sea level.[5] The seamount is made of basalt, and its depth is due to a general subsidence of the entire region and not because of erosion.[6]

Enewetak has a mean elevation above sea level of 10 feet (3.0 m).[7]

History

Humans have inhabited the atoll since about 1,000 BCE.[8] The first European visitor to Enewetak, Spanish explorer Alvaro de Saavedra, arrived on 10 October 1529.[9][10] In 1794 sailors aboard the British merchant sloop Walpole called the islands "Brown's Range" (thus the Japanese name "Brown Atoll"). It was visited by about a dozen ships before the establishment of the German colony of the Marshall Islands in 1885. Along with the rest of the Marshalls, Enewetak was captured by the Imperial Japanese Navy in 1914 during World War I and mandated to the Empire of Japan by the League of Nations in 1920. The Japanese administered the island under the South Pacific Mandate, but mostly left local affairs in hands of traditional local leaders until the start of World War II.

In November 1942, the Japanese built an airfield on Engebi Island; because they used it only for refueling planes between Truk and islands to the east, no flying personnel were stationed there and the island had only token defenses. When the Gilberts fell to the United States, the Imperial Japanese Army assigned the 1st Amphibious Brigade, a unit formed from the 3rd Independent Garrison unit previously stationed in Manchukuo, to defend the atoll. The 1st Amphibious arrived on January 4, 1944. Of the 3,940 men in the brigade, 2,586 were left to defend Eniwetok Atoll, supplemented by aviation personnel, civilian employees, and laborers, but were unable to finish fortifying the island before the American assault. During the Battle of Eniwetok in February 1944, the United States captured Enewetak in a five-day amphibious operation, with major combat on Engebi Islet, the most important Japanese installation on the atoll. Combat also occurred on the main islet of Enewetak itself and on Parry Island, site of a Japanese seaplane base.

Following its capture, the anchorage at Enewetak became a major forward naval base for the U.S. Navy. The daily average of ships present during the first half of July 1944 was 488; during the second half of July the daily average number of ships at Enewetak was 283.[11]

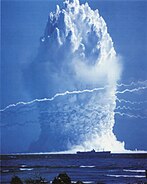

Following the end of World War II, Enewetak came under the control of the United States as part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands until the independence of the Marshall Islands in 1986. During its tenure, the United States evacuated the local residents many times, often involuntarily,[citation needed] and the atoll was used for nuclear testing as part of the Pacific Proving Grounds. Before testing commenced, the U.S. exhumed the bodies of United States servicemen killed in the Battle of Enewetak and buried there and returned them to the United States to be re-buried by their families. Forty-three nuclear tests were fired at Enewetak from 1948 to 1958.[12] The first hydrogen bomb test, code-named Ivy Mike, occurred in late 1952 as part of Operation Ivy; it vaporized the islet of Elugelab. This test included the use of B-17 Flying Fortress drones to fly through the radioactive cloud for the purpose of testing onboard samples. B-17 mother ships controlled the drones while flying within visual distance of them. In all 16 to 20 B-17s took part in this operation, of which half were controlling aircraft and half were drones. For examination of the explosion clouds of the nuclear bombs in 1957/58 several rockets (mostly from rockoons) were launched.

Aerial view of the Cactus dome.

A radiological survey of Enewetak was conducted in from 1972 to 1973.[13] In 1977, the United States military began decontamination of Enewetak and other islands. During the three-year, $100 million cleanup process, the military mixed more than 111,000 cubic yards (85,000 m3) of contaminated soil and debris[14] from the various islands with Portland cement and buried it in an atomic blast crater on the northern end of the atoll's Runit Island.[15][16] The material was placed in the 30-foot (9.1 m) deep, 350-foot (110 m) wide crater created by the May 5, 1958, "Cactus" nuclear weapons test. A dome composed of 358 concrete panels, each 18 inches (46 cm) thick, was constructed over the material. The final cost of the cleanup project was $239 million.[14] The United States government declared the southern and western islands in the atoll safe for habitation in 1980,[17] and residents of Enewetak returned that same year.[18]

Section 177 of the 1983 Compact of Free Association between the Government of the United States and the Government of the Marshall Islands[19] establishes a process for Marshallese to make a claim against the United States government as a result of damage and injury caused by nuclear testing. That same year, an agreement was signed to implement Section 177 which established a $150 million trust fund. The fund was intended to generate $18 million a year, which would be payable to claimants on an agreed-upon schedule. In the event the $18 million a year generated by the fund was not enough to cover claims, the principal of the fund could be used.[20][21] A Marshall Islands Nuclear Claims Tribunal was established to adjudicate claims. In 2000, the tribunal made a compensation award to the people of Enewetak consisting of $107.8 million for environmental restoration; $244 million in damages to cover economic losses caused by loss of access and use of the atoll; and $34 million for hardship and suffering.[21] In addition, as of the end of 2008, another $96.658 million in individual damage awards were made. Only $73.526 million of the individual claims award has been paid, however, and no new awards were made between the end of 2008 and May 2010.[21] Due to stock market losses, payments rates which have outstripped fund income, and other issues, the fund was nearly exhausted as of May 2010 and unable to make any additional awards or payments.[21] A lawsuit by Marshallese arguing that "changed circumstances" made Nuclear Claims Tribunal unable to make just compensation was dismissed by the Supreme Court of the United States in April 2010.[22]

The 2000 environmental restoration award included funds for additional cleanup of radioactivity on Enewetak. Rather than scrape the topsoil off the island, replace it with clean topsoil, and create another radioactive waste repository dome at some site on the atoll (a project estimated to cost $947 million), most areas still contaminated on Enewetak itself were treated with potassium.[23] Soil which could not be effectively treated for human use was removed and used as fill for a causeway connecting the two main islands of the atoll (Enewetak and Parry). The cost of the potassium decontamination project was $103.3 million.[21]

List of nuclear tests at Eniwetok

Summary

| Series | Start Date | End Date | Count | Yield Range | Total Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandstone | 14 April 1948 | 14 May 1948 | 3 | 18 - 49 kilotons | 104 kilotons |

| Greenhouse | 7 April 1951 | 4 May 1951 | 4 | 45.5-225 kilotons | 399 kilotons |

| Ivy | 31 October 1952 | 15 November 1952 | 2 | 500 kilotons - 15 megatons | 15.5 megatons |

| Redwing | 4 May 1956 | 21 July 1956 | 11 | 190 tons - 1.89 megatons | 2.555 megatons |

| Hardtack I | 28 April 1958 | 18 August 1958 | 26 | Zero - 9.3 megatons | 16.005 megatons |

| Total | 46 | 34.5463 megatons (6.6% of total test yield worldwide) |

Operation Sandstone

| Bomb | Date | Location | Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-Ray | 18:17 14 April 1948 (GMT) | Engebi Islet | 37 kt |

| Yoke | 18:09 30 April 1948 (GMT) | Aomon Islet | 49 kt |

| Zebra | 18:04 14 May 1948 (GMT) | Runit Islet | 18 kt |

Operation Greenhouse

| Bomb | Date | Location | Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dog | 18:34 7 April 1951 (GMT) | Runit Islet | 81 kt |

| Easy | 18:26 20 April 1951 (GMT) | Enjebi Islet | 47 kt |

| George | 21:30 8 May 1951 (GMT) | Eberiru Islet | 225 kt |

| Item | 18:17 24 May 1951 (GMT) | Enjebi Islet | 45.5 kt |

Operation Ivy

| Bomb | Date | Location | Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mike | 19:14:59.4 31 October 1952 (GMT) | Elugelab Islet | 10.4 Mt |

| King | 23:30 15 November 1952 (GMT) | Runit Islet | 500 kt |

Operation Redwing

| Bomb | Date | Location | Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lacrosse | 18:25 4 May 1956 (GMT) | Runit Islet | 40 kt |

| Yuma | 19:56 27 May 1956 (GMT) | Aomon Islet | 0.19 kt |

| Erie | 18:15 30 May 1956 (GMT) | Runit Islet | 14.9 kt |

| Seminole | 00:55 6 June 1956 (GMT) | Bogon Islet | 13.7 kt |

| Blackfoot | 18:26 11 June 1956 (GMT) | Runit Islet | 8 kt |

| Kickapoo | 23:26 13 June 1956 (GMT) | Aomon Islet | 1.49 kt |

| Osage | 01:14 16 June 1956 (GMT) | Runit Islet | 1.7 kt |

| Inca | 21:26 21 June 1956 (GMT) | Rujoru Islet | 15.2 kt |

| Mohawk | 18:06 2 July 1956 (GMT) | Eberiru Islet | 360 kt |

| Apache | 18:06 8 July 1956 (GMT) | Crater from Ivy Mike | 1.85 Mt |

| Huron | 18:12 21 July 1956 (GMT) | Off Flora Islet | 250 kt |

Operation Hardtack I

| Bomb | Date | Location | Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yucca | 18:15 28 April 1958 (GMT) | 157 KM N of Eniwetok-Atoll | 1.7 kt |

| Cactus | 18:15 5 May 1958 (GMT) | Runit Islet | 18 kt |

| Fir | 17:50 11 May 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 1360 kt |

| Butternut | 18:15 11 May 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 81 kt |

| Koa | 18:30 12 May 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 1370 kt |

| Wahoo | 01:30 16 May 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 9 kt |

| Holly | 18:30 20 May 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 5.9 kt |

| Nutmeg | 21:20 21 May 1958 (GMT) | Bikini-Atoll | 25.1 kt |

| Yellowwood | 2:00 26 May 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok Lagoon | 330 kt |

| Magnolia | 18:00 26 May 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 57 kt |

| Tobacco | 02:50 30 May 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 11.6 kt |

| Sycamore | 03:00 31 May 1958 (GMT) | Bikini-Atoll 3,5 m underwater | 92 kt (5000 kt) |

| Rose | 18:45 2 June 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 15 kt |

| Umbrella | 23:15 8 June 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok Lagoon | 8 kt |

| Walnut | 18:30 14 June 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 1.45 kt |

| Linden | 03:00 18 June 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 11 kt |

| Elder | 18:30 27 June 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 880 kt |

| Oak | 19:30 28 June 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok Lagoon | 8.9 Mt |

| Sequoia | 18:30 1 July 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 5.2 kt |

| Dogwood | 18:30 5 July 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 397 kt |

| Scaevola | 04:00 14 July 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 0 kt |

| Pisonia | 23:00 17 July 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 255 kt |

| Olive | 18:15 22 July 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 202 kt |

| Pine | 20:30 26 July 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 2000 kt |

| Quince | 02:15 6 August 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 0 kt |

| Fig | 04:00 18 August 1958 (GMT) | Eniwetok-Atoll | 0.02 kt |

Eniwetok Airfield

Men from the 110th Naval Construction Battalion arrived on Eniwetok between 21 and 27 February 1944 and began clearing the island for construction of a bomber airfield. A 6,800-foot (2,100 m) by 400-foot (120 m) runway together with taxiways and supporting facilities was built. The first plane landed on 11 March and by 5 April the first operational bombing mission was conducted.[24] The base was later named for Lieutenant John H. Stickell.[25][26]

In mid-September 1944 operations at Wrigley Airield on Engebi Island were transferred to Eniwetok.[27]

US Navy and Marine units based at Eniwetok included:

- VB-102 operating PB4Y-1s from 12–27 August 1944[28]

- VB-108 operating PB4Y-1s from 11 April-10 July 1944[29]

- VB-109 operating PB4Y-1s from 5 April-14 August 1944[30]

- VB-116 operating PB4Y-1s from 7 July-27 August 1944[31]

- VPB-121 operating PB4Y-1s from 1 March-3 July 1945[32]

- VPB-144 operating PV-2s from 27 June 1945 until September 1946[33]

The airstrip is now abandoned and its surface partially covered by sand.

Parry Island seaplane base

The Imperial Japanese Navy had developed a seaplane base on Parry Island and following its capture on 22 February Seebees from the 110th Naval Construction Battalion expanded the existing base building a coral-surfaced parking area and shops for minor aircraft and engine overhaul. A marine railway was installed on an existing Japanese pier and boat-repair shops were also erected.[34]

US Navy and Marine units based at Parry Island included:

- VP-13 operating PB2Y-3s from 26 February-22 June 1944[35]

- VP-16 operating PBM-3Ds from 7 June-1 August 1944[35]

- VP-21 operating PBM-3Ds from 19 August-17 October 1944 and from 15 July-11 September 1945[36]

- VP-23 operating PBY-5As from 20 August 1944-9 April 1945[37]

- VP-MS-6 operating PBM-5Es from 1 February 1948 in support of Operation Sandstone[38]

- VP-102 operating PB2Y-3s from 3 February-30 August 1944[39]

- VP-202 operating PBM-3Ds from 24 February-1 March 1944[40]

- VPB-19 operating PBM-3Ds from 2 November 1944-12 February 1945 and 6 March 1945-January 1946[41]

- VPB-22 operating PBM-3Ds from 10 October-30 November 1944 and from 25 June-7 August 1945[42]

Gallery

Notes

- ↑ Marshallese-English Dictionary – Place Name Index

- ↑ Hacker, Barton C. (1994). Elements of controversy : the Atomic Energy Commission and radiation safety in nuclear weapons testing, 1947–1974. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 14. ISBN 0520083237.

- ↑ the-nuclear-trash-can

- ↑ Clouard, Valerie; Bonneville, Alain (2005). "Ages of Seamounts, Islands and Plateaus on the Pacific Plate". In Foulger, Gillian R.; Natland, James H.; Presnall, Dean C. et al.. Plates, Plumes, and Paradigms. Boulder, Colo.: Geological Society of America. pp. 71–90 [p. 80]. ISBN 0813723884.

- ↑ Ludwig, K. R.; Halley, R. B.; Simmons, K. R.; Peterman, Z. E. (1988). "Strontium-Isotope Stratigraphy of Enewetak Atoll". pp. 173–177 [p. 173–174]. Digital object identifier:10.1130/0091-7613(1988)016<0173:SISOEA>2.3.CO;2.

- ↑ Schlanger, S. O.; Campbell, J. F.; Jackson, M. W. (1987). "Post-Eocene subsidence of the Marshall Islands Recorded By Drowned Atolls on Harrie and Sylvania Guyots". In Keating, B. H.; et al.. Seamounts, Islands, and Atolls. Geophysical Monograph Series. 43. Washington, D.C.: American Geophysical Union. pp. 165–174 [p. 173]. ISBN 0875900682.

- ↑ Munk, Walter; Day, Deborah (2004). "Ivy-Mike". pp. 97–105 [p. 98]. Digital object identifier:10.5670/oceanog.2004.53.

- ↑ Hezel, Francis X. (1983). The First Taint of Civilization: A History of the Caroline and Marshall Islands in Pre-Colonial Days, 1521–1885. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 3. ISBN 058526712X.

- ↑ Hezel, p. 16-17.

- ↑ Brand, Donald D. The Pacific Basin: A History of its Geographical Explorations The American Geographical Society, New York, 1967, p.122

- ↑ Carter, Worrall Reed. Beans, Bullets, and Black Oil: The Story of Fleet Logistics Afloat in the Pacific During World War II. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Navy, 1953, p. 163.

- ↑ Diehl, Sarah and Moltz, James Clay. Nuclear Weapons and Nonproliferation: A Reference Book. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO, 2002, p. 208.

- ↑ Johnson, Giff. "Paradise Lost." Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. December 1980, p. 27.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Schwartz, Stephen I. Atomic Audit: The Costs and Consequences of U.S. Nuclear Weapons Since 1940. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 1998, p. 380.

- ↑ Johnson, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, p. 24.

- ↑ A 15 kiloton nuclear weapon exploded but did not undergo nuclear fission on Runit, scattering plutonium over the island. Runit Island is not habitable for the next 24,000 years, which is why it was chosen for the nuclear waste repository. See: Wargo, John. Green Intelligence: Creating Environments That Protect Human Health. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009, p. 15.

- ↑ The government said that the northern islands would not be safe for inhabitation until 2010. See: Johnson, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, p. 25.

- ↑ Linsley, Gordon. "Site Restoration and Cleanup of Contaminated Areas." In Current Trends in Radiation Protection: On the Occasion of the 11th International Congress of the International Radiation Protection Association, 23–28 May 2004, Madrid, Spain. Henri Métivier, Leopoldo Arranz, Eduardo Gallego, and Annie Sugier, eds. Les Ulis: EDP Sciences, 2004, p. 142.

- ↑ The Compact was ratified by both nations in 1986.

- ↑ Louka, Elli. Nuclear Weapons, Justice and the Law. Northampton, Mass.: Edward Elgar, 2011, p. 161-162.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Graham, Bill. "Written Testimony of Bill Graham, Public Advocate (retired), Marshall Islands Nuclear Claims Tribunal." Subcommittee on Asia, the Pacific, and the Global Environment. Committee on Foreign Affairs. United States House of Representatives. May 20, 2010. Accessed 2012-11-01.

- ↑ Richey, Warren. "Supreme Court: No Review of Award for US Nuclear Weapons Tests." Christian Science Monitor. April 5, 2010.

- ↑ Cesium, which is highly radioactive, is chemically similar to potassium. Since the atoll is deficient in potassium, plants absorb cesium from the ground instead. This makes the plants inedible. Cesium also is deposited in the muscles of the human body, just as potassium is. See: Firth, Stewart (1987). Nuclear Playground. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 36. ISBN 0824811445.

- ↑ Building the Navy's Bases in World War II History of the Bureau of Yards and Docks and the Civil Engineer Corps 1940-1946. US Government Printing Office. 1947. p. 325.

- ↑ Carey, Alan (1999). The Reluctant Raiders: The Story of United States Navy Bombing Squadron VB/VPB-109 During World War II. Schiffer Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 9780764307577.

- ↑ Morison, Samuel (1975). History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Volume VI: Aleutians, Gilberts and Marshalls, June 1942-April 1944. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 306.

- ↑ Bases, p.326

- ↑ Dictionary of American Naval Aviation Squadrons - Volume 2. Naval Historical Center. p. 135.

- ↑ Squadrons, p.186

- ↑ Squadrons, p.522-3

- ↑ Squadrons, p.623

- ↑ Squadrons, p.544

- ↑ Squadrons, p.35

- ↑ Bases, p.325

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Squadrons, p.410

- ↑ Squadrons, p.233-4

- ↑ Squadrons, p.431

- ↑ Squadrons, p.267

- ↑ Squadrons, p.392

- ↑ Squadrons, p.591

- ↑ Squadrons, p.295

- ↑ Squadrons, p.236

External links

This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency website http://www.afhra.af.mil/.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Enewetak. |

- Marshall Islands site

- Entry at Oceandots.com at the Wayback Machine (archived December 23, 2010)

- Annotated bibliography for Eniwetok Atoll from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Information on legal judgements to the people of Enewetak

- Nursing a nuclear test hangover (www.watoday.com.au report on Runit Dome, August 18, 2008)

Template:Marshall Islands