| Bessas | |

|---|---|

| Native name | Βέσσας |

| Born | 470s |

| Died | after 554 |

| Allegiance | Byzantine Empire |

| Years of service | ca. 500–554 |

| Rank | magister militum |

| Wars | Anastasian War, Iberian War, Gothic War, Lazic War |

Bessas (Greek: Βέσσας, before 480 – after 554) was an East Roman (Byzantine) general of Gothic origin from Thrace, primarily active under Justinian I (reigned 527–565). He distinguished himself against the Sassanid Persians in the Iberian War and under the command of Belisarius in the Gothic War, but after Belisarius' departure from Italy he failed to confront the resurgent Goths and was largely responsible for the loss of Rome in 546. Returning east in disgrace, despite his advanced age he was appointed as commander in the Lazic War. There he redeemed himself with the recapture of Petra, but his subsequent idleness led Justinian to dismiss him and exile him in Abasgia.

Origin[]

According to Procopius of Caesarea, Bessas was born in the 470s and hailed from a noble Gothic family long established in Thrace, from among those Goths who had not followed Theodoric the Great when he left to invade Italy, then held by Odoacer, in 488.[1][2] Procopius remarks on his fluency in Gothic,[1][3] but another contemporary writer, Jordanes, claims that he hailed from the settlement of Castra Martis, comprising Sarmatians, Cemandrians and certain of the Huns (Getica 265).[1] This evidence has been variously interpreted, with most modern commentators leaning towards a Gothic identity.[4] Nevertheless, according to Patrick Amory, it is impossible from the sources at hand to draw any definite conclusion about his ethnicity. Amory maintains that Bessas was a typical example of the "blurry ethnographic identity" evidenced in 6th-century Balkan populations, especially among the military.[5]

Career in the East[]

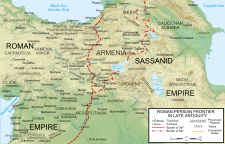

Map of the Byzantine-Persian frontier area.

Very little is known of Bessas' early life and career: he joined the East Roman army in his youth and according to Procopius was already "experienced in war" by 503, when the Anastasian War with the Sassanid Persians broke out. He took part in the war as an officer, but nothing is known of his exploits there. He is probably to be identified with a comes of the same name who was addressed in a letter of the bishop Jacob of Serugh (d. 521).[1] If this identification is valid, then Bessas was a (probably moderate) Monophysite.[6]

He reappears in 531, during the Iberian War against Persia, when he was appointed dux Mesopotamiae, with Martyropolis as his base. In this capacity, Bessas led 500 cavalry against the Persian force guarding the same frontier sector, comprising 700 Persian infantry and cavalry under the generals Gadar and Yazdgerd. The Byzantines engaged the Persians in battle on the banks of the Tigris and routed them, killing Gadar and taking Yazdgerd captive. Bessas then raided the province of Arzanene and returned to Martyropolis.[1][7] In retaliation for this success, the Persian shah Kavadh I sent against Martyropolis a large army commanded by three senior generals, Aspebedes, Mihr-Mihroe and Chanaranges. The Persians besieged the city through the autumn, digging trenches and mines, but the garrison, under Bessas and Bouzes, held firm. Finally, the approach of winter, the arrival of large East Roman forces at nearby Amida, and the news of the death of Kavadh forced the Persian commanders to raise the siege (in November or December).[1][8] Soon after their withdrawal, a force of Sabir Huns, who the Persians had hired as mercenaries, invaded Roman territory and raided as far as Antioch, but Bessas caught one of their raiding parties and destroyed it, capturing 500 horses and much booty.[1][9]

Actions in Italy[]

In 535, Bessas was appointed as one of Belisarius' lieutenants (along with Constantine and Peranius) in the expedition against the Ostrogothic kingdom of Italy.[10][11] He accompanied Belisarius in the early stages of the campaign, from Sicily to the siege of Naples in 536, and was present at the latter's fall in November.[12][13] From there the Byzantine army advanced on Rome. Belisarius sent Constantine and Bessas to capture various outlying towns, but when he learned that the new Gothic king, Witiges, was marching on Rome, he recalled them. Bessas tarried for a while near the town of Narni, which controlled the direct route from the Gothic capital, Ravenna, over the Apennines to Rome, and there met and defeated the Gothic vanguard in a skirmish.[13][14]

During the subsequent year-long siege of Rome, Bessas commanded the troops at the Porta Praenestina gate and distinguished himself in a number of skirmishes.[13] Nothing is known of his role in the subsequent events until 540, except that it was probably at about this time that he was raised to the rank of patricius.[13] In early 538, he had shielded Belisarius when the general Constantine tried to kill him during a dispute,[13][15] but by 540, when Belisarius was preparing to enter Ravenna under pretense of accepting the Gothic offer to become Emperor of the West, he clearly felt that Bessas could not be trusted, as he was sent along with other trouble-making generals such as John and Narses to occupy remote locations in Italy.[13][16] Bessas remained in Italy following the departure of Belisarius in mid-540. Justinian did not appoint an overall commander over the various generals who remained behind, and as a result they retreated to various cities and neglected to subdue the last remnants of the Ostrogoths in northern Italy, who now gathered around Ildibad. Ildibad marched on Treviso and routed a Byzantine force under Vitalius, whereupon Bessas advanced with his troops to Piacenza.[13][17] In late 541, after Totila had become king of the Goths, Bessas and the other Byzantine commanders assembled in Ravenna to co-ordinate their efforts, but the Byzantine troops were repulsed from Verona and defeated at Faventia by Totila's Goths, who then invaded Tuscany, threatening Florence, held by the general Justin. Bessas, along with John and Cyprian, marched to Justin's aid. The Goths retreated before them, but as the Byzantines pursued, the Goths fell upon them and drove them to flight, after which the Byzantine commanders dispersed again to various cities and abandoned each other to his fate. Bessas withdrew with his forces to Spoleto.[13][18]

Nothing is known of his activities from then until early 545, when he is mentioned as the garrison commander of Rome. Along with the general Conon he was responsible for the city's defence during the siege by Totila in 546.[19][20] During the siege he restricted himself to passive defence, refusing to sally forth from the walls even when Belisarius, who had landed with reinforcements at the Portus Romanus, ordered him to do so. As a result, Belisarius' attempts to succour the beleaguered city failed.[21][22] Procopius heavily criticizes Bessas for his neglect of the citizens of Rome and accuses him of enriching himself by selling the starving populace the grain he had hoarded at exorbitant prices. The civilian population were so exhausted by famine that when he finally allowed those who wanted to leave the city to do so, many simply died on the wayside, while others were killed by the Goths.[22][23] Finally, he proved negligent in the conduct of the defence, and allowed security measures to grow lax: guards slept at their posts, and patrols were discontinued. This allowed four Isaurian soldiers to contact Totila, and on 17 December, the city was betrayed to the Goths. Bessas managed to escape the city with the greater part of the garrison, but the treasure that he had amassed was left behind for the Goths to enjoy.[22][24] Following his dismal performance in Italy, Bessas was apparently recalled to Constantinople.[22]

Return to the East and command in Lazica[]

Map of Lazica and surrounding regions in Late Antiquity

In 549, a large Byzantine army under the magister militum per Armeniam Dagisthaeus had failed to capture the strategic fortress of Petra in Lazica, held by the Persians. Consequently, in 550, to general surprise—and considerable criticism, in view of his advanced age and failure at Rome—Justinian named Bessas as Dagisthaeus' successor and entrusted him with the conduct of the war in Lazica.[22][25] Bessas first sent an expeditionary force to suppress a rebellion among the Abasgians, who neighboured Lazica to the north. The expedition, under John Guzes, was successful, and the Abasgian leader Opsites was forced to flee across the Caucasus to the Sabir Huns.[26][27] In spring 551, after a long siege and thanks largely to his own perseverance and bravery, the Byzantines and their Sabir allies (some 6,000 troops) captured Petra. A few Persians continued to resist from the citadel, but Bessas ordered it torched. Following his victory, he ordered the city walls razed to the ground.[22][28][29]

If the capture of Petra redeemed Bessas in the eyes of his contemporaries, his subsequent actions tarnished it again: instead of following up his success and capture the mountain passes connecting Lazica with the Persian province of Iberia, he retired west to the Roman provinces of Pontica and busied himself with its administration.[30] This inactivity allowed the Persians under Mihr-Mihroe to consolidate Persian control over the eastern part of Lazica. The Byzantine forces in Lazica withdrew west to the mouth of the Phasis, while the Lazi, including their king Gubazes and his family, sought refuge in the mountains. Despite enduring harsh conditions in the winter of 551–552, Gubazes rejected the peace offers conveyed by envoys from Mihr-Mihroe. In 552, the Persians received substantial reinforcements, but their attacks on the fortresses held by the Byzantines and the Lazi were repulsed.[31] Bessas reappears in the campaign of 554, when he was appointed joint commander in Lazica with Martin, Bouzes and Justin. Gubazes, though, soon protested to Justinian about the incompetence of the Byzantine generals. Bessas was dismissed, his property was confiscated, and he was sent in exile among the Abasgians. Nothing more is known about him thereafter.[32][33][34]

References[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Martindale, Jones & Morris (1980), p. 226

- ↑ Amory (1997), pp. 98–99, 179

- ↑ Amory (1997), p. 105

- ↑ cf. Amory (1997), pp. 364–365

- ↑ Amory (1997), pp. 277ff.

- ↑ Amory (1997), p. 274

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu (2002), p. 94

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu (2002), pp. 95–96

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu (2002), p. 95

- ↑ Martindale, Jones & Morris (1980), pp. 226–227

- ↑ Bury (1958), p. 170

- ↑ Bury (1958), pp. 171–177

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Martindale, Jones & Morris (1980), p. 227

- ↑ Bury (1958), p. 181

- ↑ Bury (1958), pp. 191–192

- ↑ Bury (1958), pp. 212–213

- ↑ Bury (1958), pp. 227–228

- ↑ Bury (1958), pp. 230–231

- ↑ Bury (1958), pp. 235–236

- ↑ Martindale, Jones & Morris (1980), pp. 227–228

- ↑ Bury (1958), pp. 239–242

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 Martindale, Jones & Morris (1980), p. 228

- ↑ Bury (1958), pp. 238–239

- ↑ Bury (1958), p. 242

- ↑ Bury (1958), pp. 113–114

- ↑ Bury (1958), pp. 114–116

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu (2002), p. 118

- ↑ Bury (1958), p. 116

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu (2002), pp. 118–119

- ↑ Martindale, Jones & Morris (1980), pp. 228–229

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu (2002), pp. 119–120

- ↑ Bury (1958), p. 118

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu (2002), p. 120

- ↑ Martindale, Jones & Morris (1980), p. 229

Sources[]

- Amory, Patrick (1997). People and Identity in Ostrogothic Italy, 489–554. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57151-0.

- Bury, John Bagnell (1958). History of the Later Roman Empire: From the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian, Volume 2. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-20399-9. http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/secondary/BURLAT/home.html.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14687-9.

- Martindale, John Robert; Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin; Morris, J., eds (1980). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Volume II: A.D. 395–527. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20159-9.

The original article can be found at Bessas (general) and the edit history here.