| Schräge Musik | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |||||

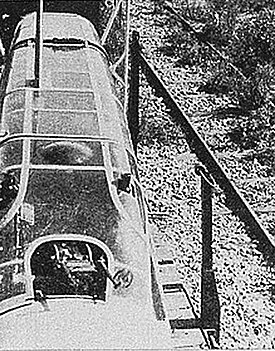

Captured Messerschmitt Bf 110G-4 showing twin-cannon Schräge Musik installation of two cannon with their muzzles just above the rear cockpit, France c. 1944. | |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

|

| ||||

Schräge Musik, derived from the German colloquialism for "Jazz Music"[1](the German word "schräg" literally means "slanted" or "oblique")[N 1] was the name given to installations of upward-firing autocannon mounted in night fighters by the Luftwaffe. A similar armament emplacement scheme, not known by the German name, was also used by both the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service and Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service during World War II for their own twin-engined night fighters, with the first victories for the Luftwaffe and the IJN's air arm occurring in May 1943.

This innovation allowed the night fighters to approach and attack Allied bombers from below, where they would be outside the bomber crew's usual field of view. Few bombers of that era (with the exception of the American heavy bombers fitted with ventral ball turrets) carried defensive guns in the ventral position. The ventral turret fitted to some early Avro Lancasters was sighted by periscope from within the fuselage, as with the first examples of the B-17E Flying Fortress's ventral turret (before the ball turret was adopted), and proved of little use. An attack by a Schräge Musik-equipped fighter was typically a complete surprise to the bomber crew, who would only realize that a fighter was close by when they came under fire. Particularly in the initial stage of operational use until early 1944, the sudden fire from below was often attributed to ground fire rather than a fighter.[2]

Background[]

World War I[]

During World War I, forward firing Lewis Guns were frequently mounted on a Foster mounting on the top wing of a biplane to fire over the revolving propeller, due to the difficulty of synchronizing this type of weapon to fire through the propeller arc. Since the gun had to be tilted-back to change ammunition drums, the gun could also be fired upwards at an angle. The guns of the Nieuport 11 and Nieuport 17 fighters, especially in British service, and the Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5a were often used in this way, to attack enemy bomber or reconnaissance aircraft from the "blind spot" below the tail. The British ace Albert Ball, in particular, was a great exponent of this technique and had developed the tactic of getting under and just behind his adversary, and with his upper-wing mounted machine gun in his SE.5, pulled down on its ratchet tracks at an angle of 45°, was able to shoot down the enemy from below. Ball also mounted another machine gun in the bottom of the cockpit to fire downward.[3] Along with many other RFC and French combat aircraft, the Nieuport 17 utilized a unique arrangement of Le Prieur rockets mounted obliquely to the interplane struts, and designed for "stand off" balloon attacks.[4]

Closeup of the Foster mounting installation of a Lewis machine gun on a SE.5a; the gun can be slid back down the curved rail for upward firing and to reload the gun's circular pan magazine

The concept of off-set or oblique mounted weaponry in night fighting was first used by Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2c night fighters to attack airships from below. RFC/RAF specialized "Comic" Home Defence night fighter variants of the Sopwith 1½ Strutter and Sopwith Camels of No. 151 Squadron RAF in 1918 were produced to combat the German bomber and airship raids over Great Britain. The armament was two Lewis mounted on twin Foster mountings in preference to the synchronized Vickers preferred for day fighting located at the upper center-section or fixed to fire upwards in a position that prevented the pilot from losing his "night vision" when the guns fired.

Sopwith Dolphin with standardized upward-firing gun installation, c. 1918

The Sopwith Dolphin, a "multi-gun" fighter design entering operational service near the end of World War I, featured an armament setup of two forward-firing Vickers machine guns in the usual location just forward of the cockpit, but also had the provision to mount a pair of Lewis machine guns located on the forward cross-tube that comprised part of the cabane strut structure, and intended to be aimed forwards and upwards as an anti-Zeppelin armament scheme, direct from the factories producing them. Similar arrangements were trialled by the Germans in 1917, when Gerhard Fieseler of Jasta 38 fitted two machine guns to an Albatros D.V, pointing upwards and forwards.

The most convoluted example of a night fighter designed to fight at high altitudes was the abortive Supermarine/Pemberton-Billing P.B.31E Nighthawk, the first project of the Supermarine Aviation Works Ltd. The prototype anti-Zeppelin fighter had a crew of three to five and an intended endurance of 9–18 hours. For armament, the Nighthawk had a 1½-pounder (37 mm) recoilless Davis gun mounted above the top wing with 20 shells that had a wide arc of fire including upward, and two .303 in (7.7 mm) Lewis guns. A trainable searchlight was nose-mounted.[5] First flown in February 1917, the lumbering fighter could only manage 60 mph (97 km/h) at 6,500 ft (1,981 m) and took an hour to climb to 10,000 ft (3,048 m), which was totally inadequate for intercepting Zeppelins. The project was summarily dropped.[6]

Interwar years[]

Westland C.O.W. Gun Fighter, c. 1930

Vickers Type 161, c. 1931

The Boulton Paul Bittern was a twin-engined night fighter (designed to Specification 27/24) with a planned armament configuration of barbette mounted guns that could be angled upwards for attack against bombers without having to enter a climb. The first of two Bittern prototypes was flown in 1927, although performance was poor and the development stopped.

The Westland C.O.W. Gun Fighter (1930) and Vickers Type 161 (1931) were designed in response to Air Ministry specification F.29/27. This called for an interceptor fighter operating as a stable gun platform for the Coventry Ordnance Works 37 mm autocannon produced by the Coventry Ordnance Works (COW). The COW gun had been developed in 1918 for use in aircraft and had been trialled on the Airco DH.4. The cannon fired 23 oz (0.65 kg) shells and was to be mounted at 45 deg or more above the horizontal. The tactic was to fly below the target bomber or airship, firing upwards into it. The gun firing trials with both types went well, with no detriment to airframe or performance, although the Westland prototype displayed "alarming" handling characteristics. Neither the Type 161 nor its competitor, the Westland C.O.W. Gun Fighter were ordered and no more was heard of this use of the aerial COW gun.[7][8][N 2]

Boulton Paul turret mounted on both the Boulton Paul Defiant and Blackburn Roc

The Boulton Paul Defiant and the naval Blackburn Roc were two late-1930s British fighter aircraft that carried their armament in turrets giving them a wide range of fire including upwards; the fire of several fighters could then be brought to bear on a target together. The Defiant was put into service in 1939 with the intention to be used against bombers despite the bombers' numerous gun positions. After becoming outclassed as a day fighter, the Defiant moved to the night fighter role where it had some success at night, typically attacking from below and slightly ahead of the target bomber, and well out of its field of defensive fire.[9]

In the United States, the twin-engine Bell YFM-1 Airacuda was designed as a "bomber-destroyer", touted to be "a mobile anti-aircraft platform".[10] Its armament included mainly forward-firing M4 37mm cannon with an accompanying gunner mounted in a forward compartment of each of the two engine nacelles. Theoretically, the cannon could be aimed in an oblique fashion. Nonetheless, the flight test and operational evaluation of the type proved troublesome and except for initial flight testing in 1937 where full armament was carried, the nacelle cannon armament and the accompanying gunner/loaders were eliminated in the final development aircraft.[11]

World War II[]

Germany[]

Development[]

Oberleutnant Rudolf Schoenert of 4./NJG 2 decided to experiment with upward firing guns in 1941 and began trying out upward-firing installations amidst scepticism from his superiors and fellow pilots.[12] The first installation was made late in 1942, in a Dornier Do 17Z-10 that was also equipped with the early UHF-band version of the FuG 202 Lichtenstein B/C radar. In July 1942, Schoenert discussed the results of his experiment with General Kammhuber, who authorized the conversion of three Dornier Do 217J-1s to add a vertical armament of four or six MG 151s. Further experimentation was carried out by the Luftwaffe flight testing centre (Erprobungsstelle) at Tarnewitz on the Baltic Sea coast through 1942, and an angle of between 60° and 75° was found to give best results, allowing a target turning at 8°/sec to be kept in the gunsight.[12]

Meanwhile, Schönert was made CO of II./NJG 5, and an armourer serving with the Gruppe, Oberfeldwebel Mahle developed a working arrangement with the unit's Bf 110s mounting a pair of MG FF/M 20 mm (0.79 in) cannon in the rear compartment of the upper fuselage, firing through twin holes in the canopy's glazing. Schönert used such a modified Bf 110 to shoot down a bomber in May 1943. From June 1943 on, an official conversion kit was produced for the Junkers Ju 88 and Dornier Do 217N fighters.[12] Between August 1943 and the end of the year, Schönert achieved 18 kills with the new gun installation.[13]

Ju 88 G-6 night fighter, note Schräge Musik installation on rear fuselage

Note completely different, more forward-located mounting of the Schräge Musik cannon on this G-6, possibly MG 151 cannon

Prior to the introduction of Schräge Musik in 1943, the Nachtjagdgeschwadern (NJG, night fighter wings) were simply equipped with heavy fighters fitted with radar in the nose and a combination of front-firing and defensive weapons. The standard interception involved approaching the target from the rear in order to get into a firing position. This presents the night fighter's crew with a much smaller target area, and Royal Air Force bombers (such as the Whitley and Wellington medium bombers), in the years just before the war, had all been fitted with twin-gunned hydraulic tail turrets, and shortly thereafter with multi-gun tail turrets, to help fend off such attacks. The relatively small calibre .303 in (7.7 mm) machine guns used, however, did not provide adequate defensive firepower.[14] The rear-gunners also maintained a watch for fighters and if warned the bomber pilots could pull evasive manouvres such as corkscrews. Night fighter pilots developed a new tactic to avoid the turret guns. Instead of approaching directly from the rear, they would approach about 1,500 ft (460 m) below the bomber. They would then pull up sharply and start firing when the nose of the bomber appeared in the gunsight. As the fighter slowed and the bomber passed over them, its wings were sprayed with cannon or machine gun rounds. This maneuver was effective, but difficult to perform. There was a significant risk of collision and if the bomb load exploded, it could take down the night fighter too.

Systems similar to the original Schräge Musik, such as the Sondergerät 500 or Jägerfaust, were tested on day fighters as well as a variety of other airframes, including the experimental Grosszerstörer (heavy destroyer). The Jägerfaust system, firing 50 mm (2 in) projectiles vertically into the lower sides of bombers, was triggered by an optical device. The pilot's only task was passing underneath the targeted bomber. The Jägerfaust was tested on the Fw 190, and was destined for installation in the Me 163B and the Me 262B. The definitive night fighter version of the Messerschmitt Me 262, the Me 262B-2, was also designed to carry such an installation, but the system did not work successfully, and it was not used operationally. Trials with the Komet, however, showed very promising results with six operational aircraft modified. On 10 April 1945, a Halifax bomber was shot down by Fritz Kelb flying a Jägerfaust-equipped Me 163B, most likely from I. Gruppe/JG 400 operating from Brandis, Germany.[15]

Interior view of Messerschmitt Bf 110G-4 Schräge Musik installation: 1. MG FF/M 2. Main drums 3. Reserve drums 4. Pressurized container with pressure-reducing gear and stop valve 5. Spent cases container 6. FPD and FF (Radio installation) 7. Weapon mount 8. Weapon recoil dampener

As new experimental aircraft were developed for the night fighter role, such as the Horten Ho 229, the Schräge Musik system was incorporated from the outset. The experimental Horten Ho 229 flying wing series had an unusual upward-firing armament proposed for testing on the V4 night fighter prototype, photoelectric fired vertically mounted rockets or recoilless guns instead of cannon armament inspired by the Jagdfaust system's design.[16]

Typical installations[]

- Dornier Do 217N: 4 × 20 mm MG 151/20

- Focke-Wulf Fw 189: 1 × 20 mm MG151/20 (used mainly on Eastern Front)

- Heinkel He 219: 2 × 30 mm MK 108

- Junkers Ju 88C/G: 2 × 20 mm MG 151/20

- Junkers Ju 388J: 2 × 30 mm MK 108

- Messerschmitt Bf 110G-4: 2 × 20 mm MG FF/M

- Messerschmitt Me 262B-2: 2 × 30 mm MK 108

- Focke-Wulf Ta 154: 2 × 30 mm MK 108

Method of sighting guns[]

In the Ju 88 G-6 night fighter, which was both fast and manouevrable, the Revi 16N gunsight was modified to allow the pilot to aim at the target by placing a reflecting mirror above the pilot’s head, parallel to a similar mirror placed behind the actual gunsight (where the eye would normally be) which itself was further to the rear, functioning together in the manner of a periscope. The Ju 88 G-6 was guided into position from sighting and final approach by commands from the radar operator, with the pilot only taking over when visual contact was made just prior to firing.[17]

What a contrast with SCHRÄGE MUSIK! Again the technique was to approach deliberately at a lower level, but this time all the night fighter pilot had to do was slow up a little, rise up below the bomber and hold formation. An NJG experte could follow his observer's directions, acquire the bomber visually, close and destroy it within 60 seconds. The firing position, with the bomber 65° to 70° above the fighter, was an almost ideal one. The fighter could see the bomber clearly, as a darker silhouette either blotting out the stars or against paler sky or high cloud. It presented the biggest possible target and reflected any light from searchlights, ground fires or TIs. With the two aircraft in close formation, there was an ideal no-deflection shot. And the fighter was perfectly safe, because it was well below the Monica beam and could not be seen by any member of the bomber's crew. The only snag was that the Luftwaffe's guns were so effective that the night fighter usually had to get out of the way very fast. It was rather like 1916, except that a Lancaster with one wing blown off tumbled downwards and backwards faster than an ignited airship.[18] [N 3]

Operational use[]

"We had dropped our bombs on a synthetic-oil plant in Gelsenkirchen, Germany the night of June 12/13, 1944 and were headed for base. In the tail gun turret I was searching in the dark for any enemy fighters who might be following us out of the target area. Suddenly I heard cannons barking loudly and saw lights flashing directly below. What the hell was that? I didn’t see the fighter – just the flashing. We took evasive action and that was it.

Schräge Musik (or Schrägwaffen, as it was also called) was first used operationally during Operation Hydra (the first instance of the Allied bombing of Peenemünde) on 17/18 August 1943. [N 4] Three waves of aircraft bombed the area, and a successful diversionary raid on Berlin by RAF Mosquitoes attracted the main Luftwaffe fighter effort and meant that only the last of the three waves was met by any sizable group of night fighters.[20] The two Groups of the third wave, 5 Group and the RCAF 6 Group, lost 29 of their 166 bombers, well over the 10% losses considered "unsustainable".[citation needed] In this raid, a total of 40 aircraft were lost: 23 Lancasters, 15 Halifaxes and two Short Stirlings.

Wide-scale adoption followed in late 1943, and by 1944, a third of all German night fighters carried upward-firing guns. Schräge Musik proved to be most successful in the Jumo 213 powered Ju 88 G-6. An increasing number of these installations used the more powerful 30 mm calibre, short-barreled MK 108 cannon, such as those retroactively fitted to the Heinkel He 219.[21] By mid-1944, however, He 219 aircrew were criticizing the MK 108 installation because its low muzzle velocity and limited range meant that the night fighter had to be positioned relatively close to the bomber being attacked, with damage ensuing from debris. They demanded that either the MK 108s be removed and replaced by MG FF/Ms or the angle of the mounting be changed. Although He 219s continued to be delivered with the twin 30 mm mounted, these were removed by front line units.[22] Using the Schräge Musik required precise timing and swift evasion; a fatally damaged bomber could fall directly upon the night fighter who had just shot it down if the fighter could not quickly turn away. The He 219 was particularly prone to this; its high wing loading at the edge of stalling speed, left it unmanouevrable, and the 61-victory night fighter ace Manfred Meurer lost his life 21/22 January 1944 when, after shooting down a Handley Page Halifax bomber, his He 219 was rammed by a Bf 110.[23]

Schräge Musik allowed German night fighters to attack undetected, using special ammunition with a faint glowing trail replacing the standard tracers, combined with a "lethal mixture of armour-piercing, explosive and incendiary ammunition."[24] Approaching from below provided the night fighter crew with the advantage that the bomber crew could not see the night fighter against the dark ground or sky, yet allowed the German crew to observe and identify the silhouette of the aircraft before they attacked. The optimum target for the night fighter was the wing fuel tanks, not the fuselage or bomb bay, because of the risk that exploding bombs would damage the attacker. “To overcome some of the problems, many NJG pilots closed the range at a lower level, below the Monica zone of coverage, until they could see the bomber above; then they pulled up into a climb with all front guns blazing. This demanded fine judgment, gave only a second or two of firing time and almost immediately brought the fighter up behind the bomber's tail turret.

Schräge Musik produced devastating results with its most successful deployment in the winter of 1943–1944. This was a time when losses became unacceptable: the RAF lost 78 of 823 bombers that attacked Leipzig on 19 February, and 96 of the 795 bombers that attacked Nuremburg on 30/31 March 1944. RAF Bomber Command was slow to react to the threat from Schräge Musik, with no reports from downed crews confirming the new menace in the skies. The sudden increase in bomber losses had often been attributed to flak. Initial reports from air gunners of German night fighters stalking their prey from below had appeared as early as 1943, but had been discounted. An urban myth developed around reports, made by RAF Bomber Command crews, who claimed "scarecrow shells" were encountered over Germany. The phenomenon was thought to be "AA shells simulating an exploding four-engined bomber and designed to damage morale. Sadly, in many cases these were actual 'kills' by Luftwaffe night fighters... It was not for many months that evidence of these deadly attacks was accepted." [25]

A detailed analysis of the damage done to returning bombers clearly indicated that the night fighters were firing from below. Defense against the attacks included mixing de Havilland Mosquito night fighters into the bomber stream, attempting to pick up radar emissions from the German night fighters.[18] Wing Commander J.D. Pattinson of 429 "Bison" Squadron, recognized an unseen danger but to him, it "was all presumption, not fact." He ordered that the mid-upper turrets be removed and the "displaced gunner would lie on a mattress on the floor as an observer, looking through a perspex blister for night fighters coming up from below."[13] While many Lancaster B. IIs had retained the FN64 ventral turret, a small number of Halifax and Lancaster bombers were unofficially fitted with a single machine gun[N 5] installation in either a ventral turret or a makeshift port directly under the mid-upper gunner station.

Even in the last year of the war, 18 months after the Peenemunde Raid, Schräge Musik night fighters were still taking a fearful toll, for example on the Mitteland-Ems Canal Raid, 21 February 1945:

On this particular night the night fighters were to score heavily. The ground radar stations responsible for initial guidance to the vicinity of the bombers did their job well, as did the airborne radar operators to whom fell the task of final location of individual targets. The path of the returning bomber stream was clearly marked by the pyres of numerous downed victims. NJG-4 was operating from Gutersloh (later an RAF base) and in the space of 20 minutes, between 20.43 and 21.03, Schnaufer and his crew, using their upward firing cannons [from a Bf 110G night fighter], shot down seven Lancasters. As it was, on that black night, four night fighter crews accounted for 28 of the 62 bombers lost out of the 800 despatched.[26]

Japan[]

Nakajima J1N at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center; note the staggered barrels of its Schräge Musik-style configuration

In 1943, Commander Yasuna Kozono of the 251st Kokutai, Imperial Japanese Navy in Rabaul came up with the idea of converting the Nakajima J1N (J1N1-C) into a night fighter. On 21 May 1943, at about the same time as the Luftwaffe's Oberleutnant Schoenert had his first victory with Schräge Musik in Europe, the field-modified J1N1-C KAI shot down two B-17s of 43rd Bomb Group attacking air bases around Rabaul. The Navy took immediate notice and placed orders with Nakajima for the newly designated J1N1-S night fighter design. This model was christened the Model 11 Gekko (月光, "Moonlight"). It required only two crew and like the KAI, had a twin 20 mm pair of Type 99 Model 1 cannon firing upward and a second pair firing downward at a forward 30° angle, placed in the fuselage behind the cabin,[27] the model of 20mm calibre Japanese aircraft autocannon based on the Oerlikon FF, a close twin to the similarly-derived German MG FF weapon use to pioneer Schräge Musik for the Luftwaffe. The Japanese Army Air Force's Mitsubishi Ki-46 "Dinah" twin engined fighter was used to test the Schräge Musik armament format in its Ki-46 III KAI version in June 1943, using a 37 mm Ho-203 cannon with 200 rounds of ammunition, the largest known calibre autocannon ordnance ever used for such an operational fitment. It was mounted in virtually the same position in the fuselage as in the Luftwaffe's own night fighters. Operational deployment began in October 1944.[28]

A Ki-45 fuselage with a Schräge Musik fitment, at the Udvar-Hazy Center museum

One of the main Japanese fighters using this device was the Kawasaki Ki-45 "Nick". The Japanese Navy air forces also used the Schräge Musik installation with the Nakajima J1N1-S "Gekko" (two or three 20mm cannons firing upwards, some had two firing downwards),[29] and a pair of 20 mm Type 99 cannons in the Nakajima C6N1-S "Myrt".[30]

United Kingdom[]

The single surviving complete example of the type is a Defiant I, N1671, on display as a night fighter at the Royal Air Force Museum.[31]

The Boulton Paul Defiant "turret fighter" was originally conceived under the F.9/35 specification for a "two-seat day and night fighter" to defend Great Britain against massed formations[32] of unescorted enemy bombers. Regardless of the requirement, the use of its dorsal turret was predicated on the "broadside" fighter interception and combined fighter attack tactic in bomber interception. The circumstances that caused the woeful Defiant to take on single-seat fighters led to catastrophic results in 1940 over France and during the Battle of Britain.[33] With untenable losses in day operations, the Defiant was transferred to night fighting and there the type achieved some success. Defiant night fighters typically attacked enemy bombers from below in a similar manoeuvre to the later successful German Schräge Musik attacks, more often from slightly ahead or to one side, rather than from directly under the tail. During the winter Blitz on London of 1940–41, the Defiant equipped four squadrons, shooting down more enemy aircraft than any other type.[34] The Defiant Mk II was fitted with AI.IV radar and a Merlin XX engine. A total of 207 Defiant Mk IIs were built, but the use of the turret fighter as a night fighter was short-lived as radar-equipped Beaufighter and Mosquito night fighters entered service in 1941 and 1942, respectively.[35] Turret fighters with four 20mm cannon were specified under F.11/37, but got no further than a scaled prototype.[36] A Douglas Havoc BD126 was fitted with six upward firing machine guns in the fuselage behind the cockpit. The guns could be controlled in elevation from 30 to 50 degrees and 15 degrees in the azimuth by the gunner in the nose. The aircraft was tested at the A&AEE in 1941 and thereafter, by the GRU and Fighter Interception Unit.[37]

United States[]

Northrop P-61C

The American Northrop P-61 Black Widow night fighter could deliver a Schräge Musik–like surprise of its own, from below an enemy aircraft, because of the design of its remote dorsal turret carrying a quartet of .50 Caliber Browning M2 machine guns, designed to be elevatable to a full 90º position.

Postwar[]

F-80A experimental installation of machine guns, mounted in a Schräge Musik configuration

The Northrop F-89 Scorpion was originally designed to meet the 1945 United States Army Air Forces Army Air Technical Service Command specification ("Military Characteristics for All-Weather Fighting Aircraft") for a jet-powered night fighter to replace the P-61 Black Widow. The N-24 company proposal was armed with four 20 mm (.79 in) cannon in a unique trainable nose turret that could rotate 360˚ with the guns able to elevate to 105˚.[38] Ultimately, the F-89 design abandoned the swiveling nose turret in favor of a more standard front-firing cannon arrangement.[39]

In 1947, the United States Air Force tested a Schräge Musik gun installation on a Lockheed F-80A Shooting Star standard "day fighter" aircraft (s/n 44-85044) to study the ability to attack Soviet bombers from below. Twin 0.5 in (12.7 mm) machine guns were fixed in an oblique mount.[40]

A final attempt to exploit a fully traversing turret was found in the original 1948 design of the Curtiss-Wright XF-87 Blackhawk all-weather jet fighter interceptor. Armament was to be a nose-mounted, powered turret containing four 20 mm (.79 in) cannon, but this installation was only fitted to the mock-up and never incorporated in the two prototypes.[41]

Some Soviet jet fighter prototypes of the late-1940s/early-1950s era included cannon mounted in the nose that were capable of being trained in elevation, however none achieved production status.[citation needed]

Analysis[]

Freeman Dyson, who was an analyst for Operations research of RAF Bomber Command in World War II, commented on the effectiveness of Schräge Musik:

The cause of losses... killed novice and expert crews impartially. This result contradicted the official dogma... I blame the ORS and I blame myself in particular, for not taking this result seriously enough... If we had taken the evidence more seriously, we might have discovered Schräge Musik in time to respond with effective countermeasures.

—Freeman Dyson[42]

See also[]

References[]

- Notes

- ↑ As a colloquialism, schräge can also be translated as "weird", "strange", "off-key" or "abnormal" as in the English "queer".

- ↑ The COW 37 mm was also trialled on flying boats for use against naval vessels.

- ↑ Monica, developed at the Bomber Support Development Unit in Worcestershire, was a range-only tail warning radar for bombers, introduced by the RAF in the spring of 1942. Officially known as ARI 5664, it operated at frequencies of around 300 MHz. German night fighters equipped with special detectors could home in on Monica and after July 1944, the units were removed from RAF bombers.

- ↑ Peenemünde is a village in the northwest of the German island of Usedom on the Peene river, on the easternmost part of the German Baltic coast.

- ↑ Predominately .303 calibre machine guns were fitted but the Canadian units tended to use 0.5 in (12.7 mm) machine guns.

- Citations

- ↑ Gustin, Emmanuel. "Upward firing guns." The WWII Fighter Gun Debate, 1999. Retrieved: 18 June 2012.

- ↑ Wilson 2008, p. 3.

- ↑ Mason 1997, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ "Le Prieur Rockets". First World War.com. Retrieved: 1 October 2010.

- ↑ Mason 1992, p. 60.

- ↑ Bruce 1969, p. 69.

- ↑ Andrews and Morgan 1988, pp. 242–246.

- ↑ James 1991, pp. 198–199.

- ↑ Mondey 2002, p. 41.

- ↑ Winchester 2005, p. 74.

- ↑ Norton 2008, p. 123.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Aders 1979, p. 67.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Schräge Musik & The Wesseling Raid: 21/22 June 1944." 207 Squadron Royal Air Force Association. Retrieved: 30 September 2010.

- ↑ Hastings 1999, p. 45.

- ↑ de Bie, Rob. "Komet weapons: SG500 Jägerfaust." xs4all.nl. Retrieved: 30 September 2010.

- ↑ "Hitler's Stealth Fighter Re-created." National Geographic, 25 June 2009. Retrieved: 30 September 2010.

- ↑ Bowers 1982, p. 20.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Gunston 2004, p. 98.

- ↑ "Leonard Isaacson." Ex Air Gunners, July 2001. Retrieved: 1 October 2010.

- ↑ 'The Peenemünde Raid', Martin Middlebrook (Phoenix 2000)

- ↑ Mondey 2006, p. 97.

- ↑ Aders 1979, pp. 137, 190.

- ↑ Aders 1979, pp. 153, 191.

- ↑ Hincliffe 1996, p. 138.

- ↑ "Blundering to victory... aviation technology vs the Allied establishment in WW2." BBC, 23 June 2001. Retrieved: 1 October 2010.

- ↑ Mason 1989, p. 157.

- ↑ Mondey 2006, p. 219.

- ↑ Mondey 2006, p. 209.

- ↑ Mondey 2006, pp. 219–220.

- ↑ Mondey 2006, p. 218.

- ↑ Bowyer 1970, p. 270.

- ↑ Buttler 2004, p. 51.

- ↑ Mondey 2002, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Taylor 1969, p. 326.

- ↑ Scutts 1993, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Buttler (2004) pp56-59

- ↑ Mason 1998, p. 56.

- ↑ Davis and Menard 1990, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Air International, July 1988, p. 46.

- ↑ "Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star." aviationspectator.com. Retrieved: 28 September 2010.

- ↑ Boyne 1975, p. 36.

- ↑ Dyson, F. "A Failure of Intelligence." Technology Review, Nov-Dec 2006. Retrieved: 28 September 2010.

- Bibliography

- Aders, Gebhard. History of the German Night Fighter Force 1917–45. London: Jane's Publishing Company, 1979. ISBN 978-0-354-01247-8.

- Andrews, C.F. and E.B. Morgan'. Vickers Aircraft since 1908. London: Putnam, 2nd ed., 1988. ISBN 0-85177-815-1.

- Boyne, Walt. "A Fighter for All Weather... Curtiss XP-87 Blackhawk." Wings, Vol. 5, No. 1, February 1975.

- Bowers, Peter W. "Junkers Ju 88: Demon in the Dark." Wings, Vol. 12, No. 2, August 1982.

- Bruce, J.M. Warplanes of the First World War, Volume Three: Fighters. London: Macdonald, 1969. ISBN 356-01490-8.

- Buttler, Tony. British Secret Projects: Fighters & Bombers 1935-1950. Hinckley, UK: Midland Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-85780-179-2.

- Bowyer, Michael J.F. "The Boulton Paul Defiant." Aircraft in Profile, Vol. 5. London, Profile Publications Ltd., 1966.

- Davis, Larry and Dave Menard. F-89 Scorpion in action (Aircraft Number 104). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications Inc., 1990. ISBN 0-89747-246-2.

- Gunston, Bill. Night Fighters: A Development and Combat History. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2004, First edition 1976. ISBN 978-0-7509-3410-7.

- Hastings, Sir Max. Bomber Command (Pan Grand Strategy Series). London: Pan Books, 1999. ISBN 978-0-330-39204-4.

- Hinchliffe, Peter. Other Battle: Luftwaffe Night Aces vs. Bomber Command. Minneapolis, MN: Zenith Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-7603-0265-1.

- James, Derek N. Westland Aircraft since 1915. London: Putnam, 1991. ISBN 0-85177-847-X.

- Mason, Francis K. The Avro Lancaster. Bucks, UK: Ashton Publications Ltd., First edition 1989. ISBN 978-0-946627-30-1

- Mason, Francis K. The British Fighter Since 1912. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1977. ISBN 1-55750-082-7.

- Mason, Tim. The Secret Years: Flight Testing at Boscombe Down 1939-1945. Crowborough, UK: Hikoki Publications, 2010, First edition 1998. ISBN 978-1-90210-914-5.

- Mondey, David. The Hamlyn Concise Guide to Axis Aircraft of World War II. London: Bounty Books, 2006. ISBN 0-7537-1460-4.

- Mondey, David. The Hamlyn Concise Guide to British Aircraft of World War II. London: Chancellor Press, 2002. ISBN 1-85152-668-4.

- Norton, Bill. U.S. Experimental & Prototype Aircraft Projects: Fighters 1939-1945. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-58007-109-3.

- "Scorpion with a Nuclear Sting: Northrop F-89". Air International, July 1988, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp. 44–50. Bromley, UK: Fine Scroll. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Scutts, Jerry. Mosquito in Action, Part 1. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications Inc., 1993. ISBN 0-89747-285-3.

- Taylor, James and Martin Davidson. Bomber Crew. London: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd, 2004. ISBN 978-0-340-83871-6.

- Taylor, John W.R. "Boulton Paul Defiant." Combat Aircraft of the World from 1909 to the present. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1969. ISBN 0-425-03633-2.

- Thompson, Warren. P-61 Black Widow Units of World War 2 (Osprey Combat Aircraft 8). Oxford, UK: Osprey, 1998. ISBN 978-1-85532-725-2.

- Wilson, Kevin. Men Of Air: The Doomed Youth Of Bomber Command (Bomber War Trilogy 2). London: Phoenix, 2008. ISBN 978-0-7538-2398-9.

- Winchester, Jim. "Bell YFM-1 Airacuda". The World's Worst Aircraft. London: Amber Books, 2005. ISBN 1-904687-34-2.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Schräge Musik. |

| Look up schräge in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

The original article can be found at Schräge Musik and the edit history here.