| Alanson Merwin Randol | |

|---|---|

Brevet Captain Alanson Merwin Randol at Harrison's Landing, July/August 1862 | |

| Born | October 23, 1837 |

| Died | May 7, 1887 (aged 49) |

| Place of birth | Newburgh, New York |

| Place of death | New Almaden, California |

| Place of burial |

San Francisco National Cemetery San Francisco, California Officer's Circle, Plot 37, Grave 5 |

| Allegiance |

Union |

| Service/branch | United States Military Academy |

| Years of service | 1855-1887 |

| Rank |

|

| Unit |

1st U.S. Artillery |

| Commands held |

Battery E, 1st U.S. Artillery |

| Battles/wars |

American Civil War Great Railroad Strike of 1877 |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Beck Guion (1869-1887) |

| Signature |

|

Alanson Merwin Randol (October 23, 1837 – May 7, 1887) was a United States Army officer who served the Union in the Regular Army artillery and the 2nd New York State Volunteer Cavalry Regiment during the American Civil War.

Early life[]

Randol was born Newburgh, New York, the third son born to Alanson and Mary Randol (née Butterworth). He had six siblings. His mother died in 1846 when Randol was eight years old, and his father was remarried to Caroline Perry in 1847. Alanson, Sr. was an overseer at the United States Assay Office in New York (the modern-day Mint) and a prominent member of his local Methodist congregation. The 1850 United States Census listed Randol as living in Redding, Connecticut where he attended the Redding Institute, a private Christian liberal arts boarding school administered by Professor Daniel Sanford. In 1855, Randol secured an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York on the recommendation of New York State Judge Advocate General Elijah Ward.

Randol finished five years of instruction at West Point; his class began with 61 cadets in 1855 and ended with 41 at graduation in 1860. Prominent classmates in his year included Horace Porter, James H. Wilson, John M. Wilson, Stephen D. Ramseur, Alexander C.M. Pennington, Jr., and Wesley Merritt. He also associated with George A. Custer and Morris Schaff. Randol maintained a generally-high academic standing (in the top 15 of his class during four of five years) and graduated 9th of 41 cadets in the Class of 1860.

His father committed suicide in 1859 during Randol's fourth year at West Point.

Pre-war career[]

Randol was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the United States Artillery on July 1, 1860. He was then transferred to the Ordnance Corps to serve at Benicia Arsenal near San Francisco, California from 1860 to 1861 as a full second lieutenant from November 1860. During the period leading up to the Confederate siege of Fort Sumter, Randol and the men of the isolated Benicia Arsenal waited for word of whether or not there would be war. In a letter sent home to his brother James B. Randol in February 1861, he indicated that there were rumors of Secessionist elements considering an attempt to seize the arsenal, but that the forces of the Federal government were prepared to hold the installation. Even before Fort Sumter, he was aware that he would likely be sent east in the event of rebellion.

Civil War Service[]

Return to the Eastern Theater[]

Following the siege of Fort Sumter, Randol was indeed ordered back east to join the fighting in the Eastern Theater. On May 14, 1861, he was promoted to first lieutenant in the artillery service, and on the way to Washington, D.C. he served for a time with General John C. Fremont's Department of the West, commanding a battery of the 1st Missouri Light Artillery from August to December 1861. Arriving in Washington, D.C., Randol was ordered to join the artillery defenses of the capital under Colonel George W. Getty of the Second Brigade, Artillery Reserve. On January 1, 1862, he assumed command of Battery E, 1st U.S. Artillery, then consisting of four 12-pounder cannons and two 6-pounder howitzers. These were soon replaced with six Model 1857 light 12-pounder smoothbore "Napoleon" guns. The battery was understrength, having only recently returned from the South where it had been present for hard duty throughout the siege of Fort Sumter under Captain Abner Doubleday; on February 23, 1862, the unit was merged with Battery G, 1st U.S. Artillery (including two new sections chiefs, Lieutenants Egbert W. Olcott and Edward B. Hill), creating an amalgamated artillery company known thereafter as Battery E & G, 1st U.S. Artillery, or "Randol's Battery."

Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days Battles[]

On March 10, 1862, Battery E & G joined Major General George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac as it embarked upon the Peninsula Campaign on Virginia's York-James Peninsula. It was attached to the Artillery Reserve under Colonel Henry J. Hunt. Arriving by sea and landing at Fortress Monroe, the battery joined the siege of Yorktown, then moved westward with the Army of the Potomac to the Chickahominy River; following the Battle of Fair Oaks, during which time it had stood picket north of the river, the battery was stationed near the Woodbury Bridge near the headquarters of McClellan near Savage's Station until June 29, 1862. When General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia shook McClellan's confidence with a string of heavy blows opening the Seven Days Battles at Beaver Dam Creek/Mechanicsville and Gaines' Mill, the Union commander ordered the V Corps (then north of the Chickahominy) to cross the river and follow the rest of the Army of the Potomac on a retreating movement toward the perceived safety of the James River near Malvern Hill. This massive redeployment was undertaken between June 29–30, 1862.

Battle of Glendale/New Market Road[]

(Main: Battle of Glendale)

In the early morning of June 29, 1862, Battery E & G was ordered to proceed from the Woodbury Bridge to the new camp of the Artillery Reserve in the White Oak Swamp north of Malvern Hill. While the rest of the Artillery Reserve was slated to move with the Army to Malvern Hill, Randol's Battery was tasked with temporary duty attached to Brigadier General George A. McCall's Third Division, V Corps to replace Battery C, 5th U.S. Artillery (commanded by mortally-wounded Captain Henry De Hart) which had been badly mauled at Gaines' Mill. The Third Division itself, consisting mostly of volunteer infantry regiments of the Pennsylvania Reserves, had sustained heavy losses throughout the previous battles north of the Chickahominy and was not fit for a prolonged fight. Randol joined the Third Division in the afternoon of June 29, accompanying elements of Colonel William Averell's 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry and Captain Henry Benson's Battery M, 2nd U.S. Artillery (Horse Artillery Brigade) to join McCall's division as it marched toward its overnight objective: the defense of the critical Glendale junction of the New Market and Quaker Roads, where the Army of the Potomac would be required to pass on its route to Malvern Hill. McClellan knew that Lee's likely objective would be the bisection of the Army of the Potomac in transit while it was most vulnerable—failure to protect its flanks would spell certain disaster. McCall's division, in concert with elements of the divisions of Generals Sedgwick, Hooker, Kearny, Slocum and Smith, would deploy along a north-to-south line from the White Oak Swamp to Malvern Hill, parallel to the road, in order to check against any Confederate advance until the Army was safely past.

Overnight, the division got lost along the road: Randol's Battery, following McCall's three brigades under the commands of Colonel Seneca G. Simmons and Brigadier Generals George G. Meade and Truman Seymour, managed in the darkness to overshoot the junction of the roads at Glendale and end up lost approximately 1.5 miles west of their objective. Meade discovered the error around midnight on June 30, when Averell and Benson's advanced pickets met Confederate skirmishers moving in the opposite direction. Randol's own cannoneers reported encountering Confederate sentries in the dark approximately 100 yards west of their guns, then-deployed in an open field north of the New Market Road.

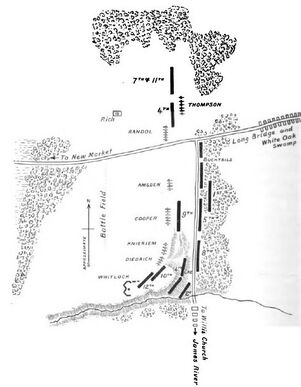

McCall's Line at Glendale/New Market Crossroad, June 30, 1862

At approximately 4:00 AM on June 30, the battery moved east with McCall's column as it retraced its path to Glendale, arriving after dawn and believing they had marched safely beyond Federal lines. McCall's division waited for orders until approximately noon, unaware that they were, in fact, the extreme western flank of the Union Army and that the Confederate main body under Major Generals James Longstreet and Ambrose P. Hill were rapidly approaching to assault the crossroad. It was not until Meade and Seymour reconnoitered the trees west of the open field in which the division was bivouacked that they discovered there was practically nothing standing between the rebels and the Third Division, V Corps. They immediately alerted McCall, who deployed his brigades for battle.

Randol's Battery was attached to Meade's Second Brigade, forming the extreme right flank of McCall's line overlooking an open field to the west which sloped downward for 400 yards toward a creek along a line of heavy pine trees opposite the Federal line. To his right, McCall's division met Kearny's, and to his left, two Pennsylvania Volunteer Artillery batteries were deployed at the center, and on the far-left, two New York Volunteer Artillery batteries also on loan from the Artillery Reserve.

Heavy fighting took place as Confederate units emerged from the woods opposite in piecemeal fashion, offering probing attacks along the whole of McCall's line. The difficulty of the terrain prevented a combined assault, which allowed the Federals to focus on repulsing isolated assaults as they occurred. A massive assault emerged on McCall's left flank, made by Brigadier General James L. Kemper's brigade, which caused McCall to shift the majority of his reserves away from the right and center just before an assault was made against the center-right by Colonel Micah Jenkins' brigade, soon supported by Brigadier General Cadmus M. Wilcox's.

Charge of the Confederates upon Randol's Battery (A.C. Redwood, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War)

Randol shifted his battery's arc of fire from west to south in order to rake the advancing units from Jenkins' brigade with murderous crossfire as they advanced against the two Pennsylvania artillery batteries at the center. This was successfully done, but two of Wilcox's brigades broke from the woods along the right of the field and appeared on Randol's present right flank: he immediately ordered his battery traversed back to the west and met the first wave of Wilcox's 8th Alabama Infantry Regiment, repulsing two infantry charges with canister shot and joined by Kearny's artillery under Captain James Thompson (Battery G, 2nd U.S. Artillery) in parallel to the right. The line might have sustained another charge, but at this moment when the second Confederate charge broke, Randol's supporting infantry (either the 4th Pennsylvania Reserve or the 7th Pennsylvania Reserve) rose and charged after the rebels in the front of the battery, obscuring the artillery fire. They advanced for a short distance before encountering a second of Wilcox's regiments, the 11th Alabama Infantry Regiment, which fired a volley of riflery and advanced with bayonets. The Pennsylvanians broke and returned directly toward the battery, masking Battery E & G's fire until it was too late. Pursuing Confederate infantry swamped the battery and overran the guns, driving the gunners from their posts to the line of caissons.

After a struggle, with night approaching, Randol was able to rally a company of infantry with the help of Meade, McCall, and 4th Pennsylvania Reserve commander Colonel Albert Magilton. They stormed the guns and retook them after a brief, intense melee fight, but 38 artillery horses had been killed and the cannoneers were unable to drag the heavy Napoleon guns off the field before Wilcox returned with the help of two additional brigades under Brigadier Generals Lawrence O. Branch and Roger A. Pryor. The party rescued Randol's mortally-wounded section chief Lieutenant Hill, but the six 12-pounder Napoleons were abandoned to the Confederates after dark when Randol could not convince Brigadier General Samuel Heintzelman (commanding the nearby Kearny) to spare men to retrieve them.

At the close of the battle, Battery E & G, 1st U.S. Artillery was no longer a functional artillery company. Arriving at Malvern Hill, Randol reported to Colonel Hunt his losses of two men killed and nine wounded, all six guns and 38 horses, and all but two caissons and four limbers.

Malvern Hill and Glendale Court of Inquiry[]

As morning dawned and the Confederates approached to commence the Battle of Malvern Hill, Randol's enlisted men were temporarily attached to Battery I, 1st U.S. Artillery, while Randol and his remaining commissioned section chief (Olcott) offered their services to Hunt as aides-de-camp during the battle. Hunt mentioned them both in his battle report, including their assistance commanding the six 32-pounder howitzers of Captain Edward Grimm's Battery D, 1st New York Artillery Battalion in the twilight of the battle, assisting to drive away the final main Confederate thrust before Union victory. Randol and Olcott were then temporarily attached to Captain James M. Robertson's Battery B & L, 2nd U.S. Artillery (Horse Brigade).

After the Army of the Potomac settled into the new camp at Harrison's Landing, Randol was breveted to the rank of captain for "gallant and meritorious services in action" at Glendale, effective June 30, 1862. On July 6, Battery E & G, 1st U.S. was re-equipped with four light 12-pounder Napoleons from the 1st Connecticut Artillery, formed under his two section chiefs Olcott and First Sergeant James Chester.

Randol requested that a Court of Inquiry be convened to investigate the circumstances surrounding the loss of his battery at Glendale, clearly desiring that the stigma and blame associated with the lost guns be expunged from his record. He wrote Meade (then recuperating in Philadelphia from his Glendale wounds) who provided a glowing letter of reference absolving Randol from blame, instead placing the fault squarely upon his Pennsylvania Reserve infantry supports:

You may rest assured that if I do make a report I shall do full justice to the coolness and good conduct exhibited by yourself and the Staff Officers and men under your command on that unfortunate day. I am aware, and shall so state, that everything was done that could be done by yourself and command to repel the enemy and save your battery. I am also aware, and shall so state, that the loss of your battery was due to the failure of the Infantry supports to maintain that firm and determined front which I should have expected from my men had not their morale been impaired by the fatigues incident to previous battles, constant marches, loss of rest and want of food, exhausting their physical energies to such a degree that they were not able to withstand the desperate and determined onslaught of overwhelming numbers causing them to give way sooner than under other circumstances I should have expected them to have done. (George Meade to Alanson Randol, July 12, 1862)

The Court of Inquiry, comprised of two infantry and two artillery officers, met in late-July and considered all testimony and evidence. Their conclusion on July 22 was as follows:

That the supports of the battery, composed of the 4th and 7th regiments Pennsylvania reserves, failed to support the battery, but having advanced in front of the battery suddenly broke and fell back upon the battery, without unmasking it, thereby preventing its fire until the enemy were nearly in the battery; That the infantry, whose duty was to support, shamefully ran and abandoned the battery, affording it no support; That so many of the horses were either killed or wounded as to render the moving of the guns from the field utterly impracticable. That Lieut. Randol, the officers and men of the battery used their utmost exertions to save the guns, not abandoning them until the supports had retreated and the enemy had seized the guns, and they therefore faithfully performed their whole duty. (Special Orders, No. 86 - July 22, 1862)

Post-Seven Days and Second Bull Run/Manassas[]

Battery E & G, 1st U.S. was attached to Major General Joseph Hooker's Second Division of Heintzelman's III Corps for most of the time the Army of the Potomac was present at Harrison's Landing, returning to the V Corps with General George Sykes' Second Division in August 1862.

When the Army of the Potomac moved across the Peninsula toward Aquia Creek to terminate the Peninsula Campaign, V Corps continued north to join Major General John Pope's Army of Virginia beyond the Rappahannock River as it engaged Confederate forces near the old Bull Run battlefield, an action which would become the Second Battle of Bull Run/Manassas on August 29.

Throughout both days of the battle the battery was ordered to remain in place near the front, drawing constant fire though inactive. Conflicting orders and confusion nearly resulted in the loss of the battery when the enemy repulsed the Union line on the 30th. The battle was a Union defeat, and both Pope and Major General Fitz John Porter (commanding V Corps) were subject to heavy criticism for the result. Porter was court-martialed and spent years attempting to clear his name: in 1878, Randol would offer sworn testimony before a commission convened to investigate the circumstances of the battle, which eventually resulted in the overturning of Porter's court-martial and restoration of his commission.

Maryland Campaign to Fredericksburg[]

Captain Alanson Merwin Randol - 1863

Following the defeat at Second Bull Run, Battery E & G returned to Washington, D.C. and onward to Hyattstown, Maryland, where Randol attempted to re-equip his depleted battery. (Battery equipment not lost at Bull Run was in a worn state, and all unnecessary baggage and possessions not needed along the march from Harrison's Landing to the Rappahannock River which had been left behind was discovered to have been lost or stolen.)

In early September, Lee's Army of Northern Virginia invaded Maryland, and McClellan mobilized to meet him.

On September 14, Randol's Battery was held in reserve during the Battle of South Mountain.

On September 17 during the Battle of Antietam, the battery was attached to General Alfred Pleasonton's cavalry and units of the U.S. Horse Artillery Brigade. Advancing with the Army along the Boonsboro Pike, Randol relieved Robertson's Battery B & L, 2nd U.S. and engaged rebel artillery west of the Middle Bridge on Antietam Creek along the way to Sharpsburg. The rebel artillery was driven back, but Randol's battery remained in reserve for the rest of the engagement; the majority of the fighting that day took place to the northwest and southwest of their position.

On September 19, one gun of the battery was briefly engaged, and on the 20th the whole battery repulsed Confederate cavalry during the Battle of Shepherdstown. On October 11, 1862, Randol was promoted to captain. The battery remained in camp near Shepherdstown until October 30, refitting and resupplying following the campaign.

In early November, the V Corps moved with the Army of the Potomac to join newly appointed commander Major General Ambrose Burnside's campaign against Lee at Fredericksburg, engaged along the way at Snicker's Gap. Now attached to General Andrew A. Humphreys' Third Division, V Corps, Randol was appointed Humphreys' chief of artillery.

At the Battle of Fredericksburg, Battery E & G was placed near Marye's Heights on December 13. Randol was in such close proximity to the stone wall from which the Confederates fired effectively upon waves of unsuccessful infantry assaults that he was able to advise Humphreys and others the following morning of the strength of the defensive position:

Early the next morning [December 14] I was called in consultation as to the feasibility of battering down the stone wall behind which it was supposed the enemy was concealed. I reported against it, as I had by accident been near the wall the night before, and knew that what was supposed to be a stone wall bordering the field over which our troops had charged, was in reality a stone retaining wall to Marye's heights, along the base of which ran a long sunken road, in which the enemy was placed, and from which, and the rifle pits in prolongation of the road, he delivered such a deadly fire on our charging columns; that we might batter it down by a concentrated fire, but it would do no good unless the road was filled. A visit to the locality afterward confirmed me in the belief then formed and the opinion given to the council. (Alanson Randol, 1875)

At the close of the five-day battle, a decisive Confederate victory, the Army of the Potomac was so demoralized that Randol wrote to his uncle, Samuel F. Butterworth, that he was contemplating resigning his commission in the Army:

I have long contemplated asking your opinion about my resigning… the war has become distasteful to me; I can see no hope of success under our present rulers. What have we gained? I have been in nearly every battle fought in the East and, excepting Malvern and the doubtful victory of Antietam, we have been beaten in every battle! When is this to end? (Alanson Randol to Samuel Butterworth, December 20, 1862)

Mud March and Chancellorsville[]

Randol and his battery joined Burnside's infamous Mud March of January 1863, finally entering winter camp until April 28, 1863, when the battery started out for Chancellorsville: it arrived on May 1. The battery was on the move when the Confederates attacked the Army of the Potomac. Returning to the main body of the Army, Randol was ordered to support Sykes' division of V Corps near the Chancellor House until dark on May 1, when it moved north with Humphreys toward the river approximately one mile south of U.S. Ford, where it remained for the remainder of the battle mostly in reserve.

Horse Artillery Brigade and Gettysburg Campaign[]

On May 14, Battery E & G was transferred to the Captain John C. Tidball's Second Brigade of the Horse Artillery Brigade. Its four light 12-pounder Napoleons were traded-in for four 3-inch Ordnance Rifles. The battery re-trained as a "flying artillery" horse battery until June 13, when it joined Brigadier General David M. Gregg's Second Division of the Cavalry Corps. Attached to Federal cavalry in pursuit of the Confederates moving northward (eventually to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania), Randol's Battery was constantly in battle and learned to fight like horse artillerymen, utilizing rifled guns on the line of battle rather than to the rear and supported as they had been previously: "We were frequently on the skirmish line, and sometimes in advance of it, and drove the enemy's batteries and cavalry from all their positions as fast as selected, dismounting some of his guns, blowing up limbers and caissons, and killing many men and horses. The accuracy of fire of the rifles, their long range, and the ease with which they could be handled, gave us a confidence in them which was not shaken during the remainder of the war."

They were engaged in battle at Aldie, Middleburgh, and Upperville.

Battery E & G was moving with the cavalry to pursue Confederate Cavalry Major General J.E.B. Stuart when the Battle of Gettysburg began. It received orders to proceed directly to the battlefield, where it arrived on July 2 and occupied a position to the right of the Union line. On July 3, while the main action at Gettysburg was focused along the Union center at Cemetery Ridge, Randol's battery was engaged with the Cavalry Corps against Stuart's rebel cavalry several miles to the east.

Randol was breveted to the rank of major for "gallant and meritorious services" at Gettysburg, effective July 3, 1863.

Following the battle, Randol's Battery pursued the fleeing Confederate Army with the Cavalry Corps. They remained attached to the cavalry through August 1863, finally sent to Harper's Ferry and Amissville until relieved by Battery A, 4th U.S. Artillery (recently re-equipped as a horse artillery battery) and detached to the Artillery Reserve mid-month.

Captain Alanson Merwin Randol - September 1863.

Bristoe and Mine Run Campaigns[]

Randol was transferred to the command of Battery H, 1st U.S. Artillery on September 1, 1863, assuming command of the First Brigade of the Artillery Reserve. He commanded this brigade through the Bristoe Campaign, then transferred soon after to Battery I, 1st U.S. Artillery to refit the company as a horse artillery battery; Randol commanded Battery I through the Mine Run Campaign and throughout the winter of 1863–64, attached to Gregg's Second Division, Cavalry Corps.

Overland Campaign[]

In April 1864, Battery I was merged with Battery H, 1st U.S., creating the combined Battery H & I, 1st U.S. under Randol's command. In May 1864, Battery H & I joined Major General Ulysses S. Grant's Overland Campaign, present at the battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Courthouse with the Artillery Reserve, and later attached to the Second Division of the Cavalry Corps in June, present from the battles at Cold Harbor through St. Mary's Church. In July, the battery was mostly in camp refitting following heavy materiel losses during the previous campaign, rejoining Gregg's division on July 25 at First Deep Bottom, then present near the Battle of the Crater (referred to by Randol as the "mine fiasco") and Lee's Mill through July 30.

West Point[]

On August 8, 1864, Randol was detailed temporarily to the United States Military Academy as an assistant professor of mathematics and artillery tactics. His tenure as an instructor lasted from August 27 to December 12, 1864.

2nd New York Volunteer Cavalry[]

In December 1864, Randol accepted colonelcy of the 2nd New York Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, and in March 1865 that unit joined the Appomattox Campaign in the First Brigade, Third Division of the Major General Philip Sheridan's Army of the Shenandoah.

Randol was breveted to colonel for "gallant and meritorious service" on March 13, 1865, following the Battle of Five Forks.

At the Battle of Appomattox Station, the 2nd New York was preparing to make one final charge against a fortified Confederate position, an action which Randol himself described as suicidal, when the enemy raised the white flag of surrender.

Randol was present at Appomattox Court House when Robert E. Lee met Ulysses S. Grant to discuss the terms of Confederate surrender on April 9, 1865:

After we had halted, we were informed that preliminaries were being arranged for the surrender of Lee’s whole army. At this news, cheer after cheer rent the air for a few moments, when soon all became as quiet as if nothing unusual had occurred. I rode forward between the lines with Custer and Pennington, and met several old friends among the rebels, who came out to see us. Among them, I remember [Colonel John W. "Gimlet" Lea – Johnston's Brigade], of Virginia, and [Colonel Robert V. Cowan – 33rd North Carolina], of North Carolina. I saw General Cadmus Wilcox just across the creek, walking to and fro with his eyes on the ground, just as was his wont when he was instructor at West Point. I called to him, but he paid no attention, except to glance at me in a hostile manner. While we were thus discussing the probable terms of the surrender, General Lee, in full uniform, accompanied by one of his staff, and General Babcock, of General Grant’s staff, rode from the Court House towards our lines. As he passed us, we all raised our caps in salute, which he gracefully returned.

It was here, as well, that Randol encountered another famous participant of the Civil War:

After the surrender, I rode over to the Court House with Colonel Pennington and others and visited the house in which the surrender had taken place, in search of some memento of the occasion. We found that everything had been appropriated before our arrival. Mr. Wilmer McLean, in whose house the surrender took place, informed us that on his farm at Manassas the first battle of Bull Run was fought. I asked him to write his name in my diary, for which, much to his surprise. I gave him a dollar. Others did the same, and I was told that he thus received quite a golden harvest.

Post-Civil War[]

Captain Alanson Merwin Randol, ca. 1865

In June 1865, Randol ended his Civil War service as a Brevet Brigadier General before returning to Battery I, 1st U.S. Artillery and resuming his permanent rank of captain.

After the Civil War ended, the United States Army mustered out most of its temporary wartime units and the regular units resumed their pre-war operations. The 1st U.S. Artillery was posted to various East Coast installations in the following years.

Randol remained in the 1st U.S. Artillery and served in numerous locations nationwide in the years following the Civil War:

Posted at Fort Brown in Brownsville, Texas from 1865 to 1869; Fort Trumbull, Connecticut from 1869 to 1870; Fort Delaware, Delaware in 1870; Fort Wood, New York from 1870 to 1872; Fort Hamilton, New York in 1872; The Citadel in Charleston, South Carolina 1872 to 1873; Fort Barrancas, Florida 1873 to 1875; Fort Independence, Massachusetts 1875 to 1879; and Fort Warren, Massachusetts 1879 to 1881.

Randol was commander of Battery K, 1st U.S. Artillery in 1872, until transferred to Battery L, 1st U.S. Artillery on July 25, 1873.

During the election of 1874 and again in 1876, following a contentious presidential election, the 1st U.S. Artillery was sent to the Southern States to maintain order after concerns of public violence. Randol's battery was detached to New Orleans, Louisiana during the election of 1874, and to Florida and South Carolina in 1876.

In July 1877, Randol's Battery L was deployed with a battalion of Federal troops under Major John Hamilton, 1st U.S. Artillery, to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. While in transit to the city by rail near Johnstown, Pennsylvania, the train carrying the battalion was pelted with rocks thrown by rioters and derailed when struck by a freight car full of bricks rolled from a siding into the train as it passed. The soldiers established a perimeter around the wrecked train and held off the rock-throwing rioters until a second train of reinforcements arrived.

In November 1881, Randol was transferred with Battery L to the West Coast of the United States posted at the Presidio (Fort Winfield Scott) in San Francisco, California. He served for a month as Aide-de-Camp to Major General Irvin McDowell, Commander of the Department of California, until he was promoted to major, 3rd U.S. Artillery in April 1882.

In May 1882, Randol returned to the 1st U.S. Artillery, posted at the Presidio until October 1883; he was commanding officer of Fort Winfield Scott until December 1884, Fort Alcatraz in San Francisco Bay until October 1886, and Fort Canby at the mouth of the Columbia River in November 1886.

Randol wrote an essay describing his experience commanding the 2nd New York Cavalry Regiment under Custer during the Battle of Appomattox Station, as well as its role in forcing the subsequent surrender of Lee's Confederate forces at Appomattox Court House in April 1865, published while he was posted in San Francisco in 1886.

Illness and Death[]

Captain Alanson Merwin Randol, 1879. Boston, Massachusetts.

In 1886, Randol's health declined, attributed to Bright's disease. This was possibly a result of his history of exposure to yellow fever while serving in the Southern United States during the Civil War and while posted in Texas and Florida post-war. On November 22, 1886, he went on sick leave from Fort Canby to the warmer climate of San Francisco; he died of his illness on May 7, 1887, in New Almaden, California.

Randol's funeral took place at the Presidio on May 9, 1887:

All the troops at the Presidio were in the funeral procession, together with Major General Howard and staff. The body of the dead officer was borne on a caisson drawn by six horses, followed by the deceased's horse carrying his rider's saddle and boots, the latter reversed in the stirrups . . . the dead officer was interred in the Military Cemetery, and three volleys were fired over his grave.

Personal life[]

Randol was married to Elizabeth Beck Guion on January 23, 1869, at Brownsville, Texas, the daughter of United States Army chaplain Elijah Guion, Jr. They had nine children, five of whom died in infancy or childhood. Four survived to adulthood, including (later-Brigadier General) Marshall Guion Randol (1882–1965).

Randol's brother, James B. Randol, was manager of the New Almaden Quicksilver Mine. Alanson Randol died at his brother's home in New Almaden, California.

Legacy[]

Randol was a member of the Military Order or the Loyal Legion of the United States, Companion of the First Class, Insignia No. 2535.

An Endicott Era coast artillery battery at Fort Worden was named after Randol in 1904.

References[]

- Chester, James. “Statement of James Chester” in Powell, William H. The History of the Fifth Army Corps. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1896.

- Cullum, George W. Biographical Registers of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy. Vols. 1 & 2. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1891.

- Haskin, William L. “The First Regiment of Artillery,” in The Army of the United States, eds. William Haskin and Theodore Rodenbough. New York: Maynard, Merrill & Co., 1896.

- Hunt, Henry J. “Report of Henry J. Hunt, July 7, 1862“. War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series 1, Vol. 11, Part 2. Washington, D.C.: G.P.O., 1884.

- Meade, George Gordon, Jr., ed. The Life and Letters of George Gordon Meade, vol 1. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913.

- Powell, William H. The Fifth Army Corps: Army of the Potomac. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1896.

- Randol, Alanson M. “From January, 1862, to August, 1864” in Haskin, William, ed. The History of the First Regiment of Artillery. Portland, ME: B. Thurston and Company, 1879.

- Randol, Alanson M. Last Days of the Rebellion: The Second New York Cavalry (Harris' Light) at Appomattox Station and Appomattox Court House, April 8 and 9, 1865. Alcatraz Island, CA: 1886.

- "Stirring the Blood of Friend and Foe to Admiration: Lieutenant Alanson Randol's Battery E & G, 1st U.S. Artillery at the Battle of Glendale, June 30, 1862" https://historyradar.wordpress.com/blog/stirring-the-blood-of-friend-and-foe-to-admiration/

- "Testimony of Alanson M. Randol." Proceedings and Report of the Board of Army Officers, Convened by Special Orders No. 78, Headquarters of the Army, Adjutant General's Office, Washington, April 12, 1878, in the Case of Fitz John Porter, vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: G.P.O., 1879.https://www.google.com/books/edition/Proceedings_and_Report_of_the_Board_of_A/wQAgkkLR1IEC?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA89&printsec=frontcover

- United States Military Academy. Official Register of the Officers and Cadets of the United States Military Academy, West Point, New York: June 1860. West Point, NY: 1860.

- War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series 1, Vol. 11, Part 2 (Washington, D.C.: G.P.O., 1884)

Further reading[]

- American Memory: Selected Civil War Photographs. Library of Congress. Prints and Photographs Division. Washington, D.C.. Internet: http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/cwphtml/cwphome.html

- Generals and Brevets: Photographs of General Officers of the Civil War. Internet: http://web.archive.org/web/20080208215607/http://www.generalsandbrevets.com/

- Heitman, Francis B. Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army, From its Organization, September 29, 1789, to March 2, 1903. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1903.

- Register of Graduates and Former Cadets of the United States Military Academy. West Point, NY: West Point Alumni Foundation, Inc., 1970.

The original article can be found at Alanson M. Randol and the edit history here.