| Zheng He | |

|---|---|

Statue from a modern monument to Zheng He at the Stadthuys Museum in Malacca Town, Malaysia | |

| Born |

1371[1] Kunyang, Yunnan, China[1] |

| Died |

1433 (aged 61–62) At sea |

| Other names |

Ma He Sanbao |

| Occupation | Admiral, diplomat, explorer, and palace eunuch |

| Zheng He | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 鄭和 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 郑和 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ma He | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 馬和 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 马和 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sanbao | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 三寶 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 三宝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning |

Three Jewels[2] Three Treasures | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Zheng He (1371–1433), formerly romanized as Cheng Ho, was a Hui-Chinese court eunuch, mariner, explorer, diplomat and fleet admiral, who commanded expeditionary voyages to Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and East Africa from 1405 to 1433. As a favorite of the Yongle Emperor, whose usurpation he assisted, he rose to the top of the imperial hierarchy and served as commander of the southern capital Nanjing. These voyages were long neglected in official Chinese histories but have become well known in China and abroad since the publication of Liang Qihao's "Biography of Our Homeland's Great Navigator, Zheng He"[3] in 1904.[4] A trilingual stele left by the navigator was discovered on Sri Lanka shortly thereafter.

Life[]

Zheng He was the second son of a family from Kunyang,[lower-alpha 1] Yunnan.[5] He was originally born with the name Ma He.[1][6] His family were Hui people. He had four sisters[1][6][7][8] and one older brother.[1][7]

Zheng He's religious beliefs are uncertain. We know that he was born into a Muslim family[6][9][10] and that on his travels he built mosques while also spreading the worship of Mazu/Tianfei. He apparently never found time for a pilgrimage to Mecca but did send sailors there on his last voyage. He played an important part in developing relations between China and Islamic countries.[11][12] His religious beliefs may have become eclectic in his adulthood.[9][10] Zheng He also visited Muslim shrines of Islamic holy men in the Fujian province. In 1985 a Muslim-style tomb was built in Nanjing on the site of an earlier horseshoe-shape grave; it contains his clothes and headgear as his body was buried at sea.[13]

He was the great-great-great-grandson of Sayyid Ajjal Shams al-Din Omar, a Persian who served in the administration of the Mongol Empire and was the Governor of Yunnan during the early Yuan Dynasty.[14][15] His great-grandfather was named Bayan and may have been stationed at a Mongol garrisons in Yunnan.[6] His grandfather carried the title hajji.[1][16] His father had the surname Ma and the title hajji.[1][6][16] The title suggest that they had made the pilgrimage to Mecca.[1][6][16]

In the autumn of 1381, a Ming army invaded and conquered Yunnan, which was then ruled by the Mongol prince Basalawarmi, Prince of Liang.[17] In 1381, Ma Hajji (Zheng He's father) died as a casualty of the hostilities between the Ming armies and Mongol forces.[7] Dreyer (2007) states that Zheng He's father died at age 39 while resisting the Ming conquest.[17] Levathes (1996) states Zheng He's father died at age 37, but it's unclear whether it was due to helping the Mongol army or due to just being caught in the onslaught of battle.[7] Wenming, the oldest son, would bury their father outside of Kunming.[7] In his capacity, Admiral Zheng He had an epitaph engraved in honor of his father, which was composed by the Minister of Rites Li Zhigang on the Duanwu Festival of the 3rd year in the Yongle reign (1 June 1405).[18] After the fall of Kunming in Yunnan, Zheng He, then only eleven years old,[contradiction] was captured by the Ming-allied Muslim troops of Lan Yu and Fu Youde and castrated along with 380 other captives.[19][verification needed] Zheng He was captured by the Ming armies at Yunnan in 1381.[7] General Fu Youde saw Zheng He on a road and approached him to inquire about the location of the Mongol pretender.[20] Zheng He responded defiantly that he had jumped into a lake.[20] Afterwards, the general took him prisoner.[20] The young Zheng He was soon castrated before being placed in servitude of the Prince of Yan.[17] However, Levathes (1996) has stated that he was castrated in 1385.[20]

He was sent to serve in the household of Zhu Di, Prince of Yan (the future Yongle Emperor).[17][20] He was 10 years old when he entered into the service of the Prince of Yan.[21] Zhu Di was eleven years older than Zheng He.[22] Since 1380, the prince had been governing Beiping (the future Beijing),[17] which was located near the northern frontier where the hostile Mongol tribes were situated.[20][22] Zheng He would spend his early life as a soldier on the northern frontier.[20][21] He often participated in Zhu Di's military campaigns against the Mongols.[22][23] On March 2, 1390, Zheng He accompanied Zhu Di when he commanded his first expedition, which was a great victory as the Mongol leader Naghachu surrendered as soon as he realized he had fallen for a deception.[24]

Eventually, he would gain the confidence and trust of the prince.[22] Zheng He was also known as "Sanbao" during the time of service in the household of the Prince of Yan.[2] This name was a reference to the Three Jewels (triratna) in Buddhism.[25] He received a proper education while at Beiping, which he would not have had if he had been placed in the imperial capital Nanjing as the Hongwu Emperor did not trust eunuchs and believed that it was better to keep them illiterate.[2] Meanwhile, the Hongwu Emperor exterminated many of the original Ming leadership and gave his enfeoffed sons more military authority, especially those in the north like the Prince of Yan.[26]

Zheng He's appearance as an adult was recorded: he was seven chi[lower-alpha 2] tall, had a waist that was five chi in circumference, cheeks and a forehead that were high, a small nose, glaring eyes, teeth that were white and well-shaped as shells, and a voice that was as loud as a bell. It is also recorded that he had great knowledge about warfare and was well-accustomed to battle.[7][27]

The young eunuch eventually became a trusted adviser to the prince and assisted him when the Jianwen Emperor's hostility to his uncle's feudal bases prompted the 1399–1402 Jingnan Campaign which ended with the emperor's apparent death and the ascension of the Zhu Di, Prince of Yan, as the Yongle Emperor. In 1393, the Crown Prince had died, thus the deceased prince's son became the new heir apparent.[26] By the time the emperor died (24 June 1398), the Prince of Qin and the Prince of Jin had perished, which left Zhu Di, the Prince of Yan, as the eldest surviving son of the emperor.[26] However, Zhu Di's nephew succeeded the imperial throne as the Jianwen Emperor.[28] In 1398, he issued a policy known as xiaofan, "reducing the feudatories", which entails eliminating all the princes by stripping their power and military forces.[29] In August 1399, Zhu Di openly rebelled against his nephew.[30] In 1399, Zheng He successfully defended Beiping's city reservoir Zhenglunba against the imperial armies.[31][32] In January 1402, Zhu Di began with his military campaign to capture the imperial capital Nanjing.[33] Zheng He would be one of his commanders during this campaign.[33]

In 1402, Zhu Di's armies defeated the imperial forces and marched into Nanjing on 13 July 1402.[33][34] Zhu Di accepted the elevation to emperor four days later.[34] After ascending the throne as the Yongle Emperor, he promoted Zheng He as the Grand Director (Taijian) of the Directorate of Palace Servants.[34] During the New Year's day on 11 February 1404,[31] the Yongle Emperor conferred the surname "Zheng" to him (his original name was still Ma He), because he had distinguished himself defending the city reservoir Zhenglunba against imperial forces in the Siege of Beiping of 1399,[31][35] Another reason was that the eunuch commander also distinguished himself during the 1402 campaign to capture the capital Nanjing.[35] It is believed that his choice to confer the surname "Zheng" was because the eunuch's horse had been killed during the battle at Zhenglunba near Beiping at the onset of his rebellion.[36]

He was initially[when?] called Ma Sanbao: either 三寶 (s 三宝, lit. "Three Gifts") or 三保 (lit. "Three Protections", both pronounced sān bǎo).[37]

In the new administration, Zheng He served in the highest posts, as Grand Director[6][8][38] and later as Chief Envoy (正使, zhèngshǐ) during his sea voyages.

In 1424, Admiral Zheng He traveled to Palembang to confer an official seal[lower-alpha 3] and letter of appointment upon Shi Jisun, who was placed in the office of Pacification Commissioner.[39] The Taizong Shilu 27 Februari 1424 entry reports that Shi Jisun had sent Qiu Yancheng as envoy to petition the approval of the succession from his father Shi Jinqing, who was the Pacification Commissioner of Palembang, and was given permission from the Yongle Emperor.[40] On 7 September 1424, Zhu Gaozhi had inherited the throne as the Hongxi Emperor after the death of the Yongle Emperor on 12 August 1424.[41][42] When Zheng He returned from Palembang, he found that the Yongle Emperor had died during his absence.[43][44]

After the ascension of Zhu Di's son as the Hongxi Emperor, the ocean voyages were discontinued and Zheng He was instead appointed as Defender of Nanjing, the empire's southern capital. In that post, he was largely responsible for the completion of the Porcelain Tower of Nanjing, an enormous pagoda still described as a wonder of the world as late as the 19th century.

On 15 May 1426, the Xuande Emperor ordered the Directorate of Ceremonial to sent a letter to Zheng He to reprimand him for a transgression.[45] Earlier, an official[lower-alpha 4] petitioned the emperor to reward workmen who had built temples in Nanjing.[45] The Xuande Emperor responded negatively to the official for placing the costs to the court instead of the monks themselves, but he realized that Zheng He and his associates had instigated the official.[45] Dreyer (2007) noted that the nature of the emperor's words indicated that Zheng He's behaviour in this situation was the last straw, but that there's too little information about what had transpired beforehand.[45] Nevertheless, the Xuande Emperor would eventually come to trust Zheng He.[45]

In 1430, the new Xuande Emperor appointed Zheng He to command over a seventh and final expedition into the "Western Ocean" (Indian Ocean).[46] In 1431, Zheng He was bestowed with the title "Sanbao Taijian".[47]

It is generally believed that Zheng He died two years later after the return trip following the fleet's visit to Hormuz in 1433.

Expeditions[]

The route of the voyages of Zheng He's fleet.

Early 17th-century Chinese woodblock print, thought to represent Zheng He's ships.[citation needed]

The Yuan Dynasty and expanding Sino-Arab trade during the 14th century had gradually expanded Chinese knowledge of the world: "universal" maps previously only displaying China and its surrounding seas began to expand further and further into the southwest with much more accurate depictions of the extent of Arabia and Africa.[48] Between 1405 and 1433, the Ming government sponsored seven naval expeditions. The Yongle Emperor – disregarding the Hongwu Emperor's expressed wishes[49] – designed them to establish a Chinese presence and impose imperial control over the Indian Ocean trade, impress foreign peoples in the Indian Ocean basin, and extend the empire's tributary system.[citation needed] It has also been inferred from passages in the History of Ming that the initial voyages were launched as part of the emperor's attempt to capture his escaped predecessor,[48] which would have made the first voyage the "largest-scale manhunt on water in the history of China".[50]

Zheng He was placed as the admiral in control of the huge fleet and armed forces that undertook these expeditions. Wang Jinghong was appointed his second in command. Preparations were thorough and wide-ranging, including the use of such numerous linguists that a foreign language institute was established at Nanjing.[48] Zheng He's first voyage departed July 11, 1405, from Suzhou[51]:203 and consisted of a fleet of 317[52][53][54] ships holding almost 28,000 crewmen.[52]

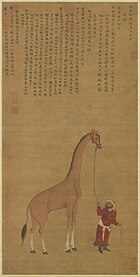

Zheng He's fleets visited Brunei, Thailand and Southeast Asia, India, the Horn of Africa, and Arabia, dispensing and receiving goods along the way.[54] Zheng He presented gifts of gold, silver, porcelain, and silk; in return, China received such novelties as ostriches, zebras, camels, and ivory from the Swahili.[51]:206[54][55][56][57] The giraffe he returned from Malindi was considered to be a qilin and taken as proof of the favor of heaven upon the administration.[58]

While Zheng He's fleet was unprecedented, the routes were not. Zheng He's fleet was following long-established, well-mapped routes of trade between China and the Arabian peninsula employed since at least the Han Dynasty. This fact, along with the use of a more than abundant amount of crew members that were regular military personnel, leads some to speculate that these expeditions may have been geared at least partially at spreading China's power through expansion.[59] During the Three Kingdoms Period, the king of Wu sent a diplomatic mission along the coast of Asia, which reached as far as the Eastern Roman Empire.[citation needed] After centuries of disruption, the Song Dynasty restored large-scale maritime trade from China in the South Pacific and Indian Oceans, reaching as far as the Arabian peninsula and East Africa.[60] When his fleet first arrived in Malacca, there was already a sizable Chinese community. The General Survey of the Ocean Shores (瀛涯勝覽, Yíngyá Shènglǎn) composed by the translator Ma Huan in 1416 gave very detailed accounts of his observations of people's customs and lives in the ports they visited.[61] He referred to the expatriate Chinese as "Tang" (唐人, Tángrén).

The Kangnido map (1402) predates Zheng's voyages and suggests that he had quite detailed geographical information on much of the Old World.

Zheng He generally sought to attain his goals through diplomacy, and his large army awed most would-be enemies into submission. But a contemporary reported that Zheng He "walked like a tiger" and did not shrink from violence when he considered it necessary to impress foreign peoples with China's military might.[62] He ruthlessly suppressed pirates who had long plagued Chinese and southeast Asian waters. For example, he defeated Chen Zuyi, one of the most feared and respected pirate captains, and returned him back to China for execution.[63] He also waged a land war against the Kingdom of Kotte on Ceylon, and he made displays of military force when local officials threatened his fleet in Arabia and East Africa.[citation needed] From his fourth voyage, he brought envoys from thirty states who traveled to China and paid their respects at the Ming court.[citation needed]

In 1424, the Yongle Emperor died. His successor, the Hongxi Emperor (r. 1424–1425), stopped the voyages during his short reign. Zheng He made one more voyage during the reign of Hongxi's son, the Xuande Emperor (r. 1426–1435) but, after that, the voyages of the Chinese treasure ship fleets were ended. Xuande believed his father's decision to halt the voyages had been meritorious and thus "there would be no need to make a detailed description of his grandfather’s sending Zheng He to the Western Ocean."[49] The voyages "were contrary to the rules stipulated in the Huang Ming Zuxun" (皇明祖訓), the dynastic foundation documents laid down by the Hongwu Emperor:[49]

Some far-off countries pay their tribute to me at much expense and through great difficulties, all of which are by no means my own wish. Messages should be forwarded to them to reduce their tribute so as to avoid high and unnecessary expenses on both sides.[64]

They further violated longstanding Confucian principles. They were only made possible by (and therefore continued to represent) a triumph of the Ming's eunuch faction over the administration's scholar-bureaucrats.[48] Upon Zheng He's death and his faction's fall from power, his successors sought to minimize him in official accounts, along with continuing attempts to destroy all records related to the Jianwen Emperor or the manhunt to find him.[49]

Although unmentioned in the official dynastic histories, Zheng He probably died during the treasure fleet's last voyage.[48] Although he has a tomb in China, it is empty: he was buried at sea.[65]

Detail of the Fra Mauro map relating the travels of a junk into the Atlantic Ocean in 1420. The ship also is illustrated above the text.

| Order | Time | Regions along the way |

|---|---|---|

| 1st voyage | 1405–1407[66] | Champa,[66] Java,[66] Palembang, Malacca,[66] Aru, Samudera,[66] Lambri,[66] Ceylon,[66] Qiulon,[66] Kollam, Cochin, Calicut[66] |

| 2nd voyage | 1407–1409[66] | Champa, Java,[66] Siam,[66] Cochin,[66] Ceylon, Calicut[66] |

| 3rd voyage | 1409–1411[66] | Champa,[66] Java,[66] Malacca,[66] Semudera,[66] Ceylon,[66] Quilon,[66] Cochin,[66] Calicut,[66] Siam,[66] Lambri, Kayal, Coimbatore[citation needed], Puttanpur |

| 4th voyage | 1413–1415[66] | Champa,[66] Kelantan,[66] Pahang,[66] Java,[66] Palembang,[66] Malacca,[66] Semudera,[66] Lambri,[66] Ceylon,[66] Cochin,[66] Calicut,[66] Kayal, Hormuz,[66] Maldives,[66] Mogadishu, Barawa, Malindi, Aden,[66] Muscat, Dhofar |

| 5th voyage | 1417–1419[66] | Champa, Pahang, Java, Malacca, Samudera, Lambri, Bengal, Ceylon, Sharwayn, Cochin, Calicut, Hormuz, Maldives, Mogadishu, Barawa, Malindi, Aden |

| 6th voyage | 1421–1422 | Champa, Bengal,[66][67][68] Ceylon,[66] Calicut,[66] Cochin,[66] Maldives,[66] Hormuz,[66] Djofar,[66] Aden,[66] Mogadishu,[66] Brava[66] |

| 7th voyage | 1430–1433 | Champa,[69] Java,[69] Palembang,[69] Malacca,[69] Semudera,[69] Andaman and Nicobar Islands,[69] Bengal,[69] Ceylon,[69] Calicut,[69] Hormuz,[69] Aden,[69] Ganbali (possibly Coimbatore),[69] Bengal,[69] Laccadive and Maldive Islands,[69] Djofar,[69] Lasa,[69] Aden,[69] Mecca,[69] Mogadishu,[69] Brava[69] |

Zheng He led seven expeditions to the "Western" or Indian Ocean. Zheng He brought back to China many trophies and envoys from more than thirty kingdoms – including King Vira Alakeshwara of Ceylon, who came to China as a captive to apologize to the Emperor for offenses against his mission.

One of a set of maps of Zheng He's missions (郑和航海图), also known as the Mao Kun maps, 1628

Zheng himself wrote of his travels:

We have traversed more than 100,000 li of immense water spaces and have beheld in the ocean huge waves like mountains rising in the sky, and we have set eyes on barbarian regions far away hidden in a blue transparency of light vapors, while our sails, loftily unfurled like clouds day and night, continued their course [as rapidly] as a star, traversing those savage waves as if we were treading a public thoroughfare…[70]

Sailing charts[]

A section of the Wubei Zhi oriented east: India in the upper left, Sri Lanka upper right, and Africa along the bottom.

Zheng He's sailing charts were published in a book entitled the Wubei Zhi (A Treatise on Armament Technology) written in 1621 and published in 1628 but traced back to Zheng He's and earlier voyages.[71] It was originally a strip map 20.5 cm by 560 cm that could be rolled up, but was divided into 40 pages which vary in scale from 7 miles/inch in the Nanjing area to 215 miles/inch in parts of the African coast.[72]

There is little attempt to provide an accurate 3-D representation; instead the sailing instructions are given using a 24-point compass system with a Chinese symbol for each point, together with a sailing time or distance, which takes account of the local currents and winds. Sometimes depth soundings are also provided. It also shows bays, estuaries, capes and islands, ports and mountains along the coast, important landmarks such as pagodas and temples, and shoal rocks. Of 300 named places outside China, more than 80% can be confidently located. There are also fifty observations of stellar altitude

Size of the ships[]

Traditional and popular accounts of Zheng He's voyages have described a great fleet of gigantic ships, far larger than any other wooden ships in history. Some modern scholars consider these descriptions to be exaggerated.[citation needed]

Chinese records[73] state that Zheng He's fleet sailed as far as East Africa. According to medieval Chinese sources, Zheng He commanded seven expeditions. The 1405 expedition consisted of 27,800 men and a fleet of 62 treasure ships supported by approximately 190 smaller ships.[74][75] The fleet included:

- "Chinese treasure ships" (宝船, Bǎo Chuán), used by the commander of the fleet and his deputies (nine-masted, about 127 metres (416 ft) long and 52 metres (170 ft) wide), according to later writers.[citation needed]

- Equine ships (馬船, Mǎ Chuán), carrying horses and tribute goods and repair material for the fleet (eight-masted, about 103 m (339 ft) long and 42 m (138 ft) wide).

- Supply ships (粮船, Liáng Chuán), containing staple for the crew (seven-masted, about 78 m (257 ft) long and 35 m (115 ft) wide).

- Troop transports (兵船, Bīng Chuán), six-masted, about 67 m (220 ft) long and 25 m (83 ft) wide.

- Fuchuan warships (福船, Fú Chuán), five-masted, about 50 m (165 ft) long.

- Patrol boats (坐船, Zuò Chuán), eight-oared, about 37 m (120 ft) long.

- Water tankers (水船, Shuǐ Chuán), with 1 month's supply of fresh water.

Six more expeditions took place, from 1407 to 1433, with fleets of comparable size.[76]

If the accounts can be taken as factual Zheng He's treasure ships were mammoth ships with nine masts, four decks, and were capable of accommodating more than 500 passengers, as well as a massive amount of cargo. Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta both described multi-masted ships carrying 500 to 1,000 passengers in their translated accounts.[77] Niccolò Da Conti, a contemporary of Zheng He, was also an eyewitness of ships in Southeast Asia, claiming to have seen 5 masted junks weighing about 2,000 tons.[78] There are even some sources that claim some of the treasure ships might have been as long as 600 feet.[79][80] On the ships were navigators, explorers, sailors, doctors, workers, and soldiers along with the translator and diarist Gong Zhen.

The largest ships in the fleet, the Chinese treasure ships described in Chinese chronicles, would have been several times larger than any other wooden ship ever recorded in history, surpassing l'Orient, 65 metres (213.3 ft) long, which was built in the late 18th century. The first ships to attain 126 m (413.4 ft) long were 19th century steamers with iron hulls. Some scholars argue that it is highly unlikely that Zheng He's ship was 450 feet (137.2 m) in length, some estimating that they were 390–408 feet (118.9–124.4 m) long and 160–166 feet (48.8–50.6 m) wide instead[81] while others put them as small as 200–250 feet (61.0–76.2 m) in length, which would make them smaller than the equine, supply, and troop ships in the fleet.[82]

One explanation for the seemingly inefficient size of these colossal ships was that the largest 44 Zhang treasure ships were merely used by the Emperor and imperial bureaucrats to travel along the Yangtze for court business, including reviewing Zheng He's expedition fleet. The Yangtze river, with its calmer waters, may have been navigable by these treasure ships. Zheng He, a court eunuch, would not have had the privilege in rank to command the largest of these ships, seaworthy or not. The main ships of Zheng He's fleet were instead 6 masted 2000-liao ships.[83][84]

Legacy[]

The pet giraffe of the Sultan of Bengal, brought from Medieval Somalia, and later taken to China[85][86][87][88] in the twelfth year of Yongle (1415).

Imperial China[]

In the decades after the last voyage, Imperial officials minimized the importance of Zheng He and his expeditions throughout the many regnal and dynastic histories they compiled. The information in the Yongle and Xuande Emperors' official annals was incomplete and even erroneous; other official publications omitted them completely.[4] Although some have seen this as a conspiracy seeking to eliminate memories of the voyages,[89] it is likely that the records were dispersed throughout several departments and the expeditions – unauthorized by (and in fact, counter to) the injunctions of the dynastic founder – presented a kind of embarrassment to the dynasty.[4]

State-sponsored Ming naval efforts declined dramatically after Zheng's voyages. Starting in the early 15th century, China experienced increasing pressure from the surviving Yuan Mongols from the north. The relocation of the capital north to Beijing exacerbated this threat dramatically. At considerable expense, China launched annual military expeditions from Beijing to weaken the Mongolians. The expenditures necessary for these land campaigns directly competed with the funds necessary to continue naval expeditions. Further, in 1449, Mongolian cavalry ambushed a land expedition personally led by the Zhengtong Emperor at Tumu Fortress, less than a day's march from the walls of the capital. The Mongolians wiped out the Chinese army and captured the emperor. This battle had two salient effects. First, it demonstrated the clear threat posed by the northern nomads. Second, the Mongols caused a political crisis in China when they released the emperor after his half-brother had already ascended and declared the new Jingtai era. Not until 1457 and the restoration of the former emperor did political stability return. Upon his return to power, China abandoned the strategy of annual land expeditions and instead embarked upon a massive and expensive expansion of the Great Wall of China. In this environment, funding for naval expeditions simply did not happen.

However, missions from Southeast Asia continued to arrive for decades. Depending on local conditions, they could reach such frequency that the court found it necessary to restrict them: the History of Ming records imperial edicts forbidding Java, Champa, and Siam from sending their envoys more often than once every three years.[90]

Southeast Asia[]

The Cakra Donya Bell, a gift from Zheng He to Pasai, now located at the Museum Aceh in Banda Aceh.

- Cult of Zheng He

Among the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia, Zheng He became the object of cult veneration.[91] Even some of his crew members who happened to stay in this or that port sometimes did as well, such as "Poontaokong" on Sulu.[90] The temples of this cult – called after either of his names, Cheng Hoon or Sam Po – are peculiar to overseas Chinese except for a single temple in Hongjian originally constructed by a returned Filipino Chinese in the Ming dynasty and rebuilt by another Filipino Chinese after the original was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution.[90] (The same village of Hongjian, in Fujian's Jiaomei township, is also the ancestral home of Corazon Aquino.)

The San Bao Temple in Malacca.

- Malacca

The oldest and most important Chinese temple in Malacca is the 17th-century Cheng Hoon Teng, dedicated to Guanyin. During Dutch colonial rule, the head of the Cheng Hoon Temple was appointed chief over the community's Chinese inhabitants.[90]

Following Zheng He's arrival, the sultan and sultana of Malacca visited China at the head of over 540 of their subjects, bearing ample tribute. Sultan Mansur Shah (r. 1459–1477) later dispatched Tun Perpatih Putih as his envoy to China, carrying a letter from the sultan to the Ming emperor. The letter requested the hand of an imperial daughter in marriage. Malay (but not Chinese) annals record that, in the year 1459, a princess named Hang Li Po or Hang Liu was sent from China to marry the sultan. The princess came with 500 high-ranking young men and a few hundred handmaidens as her entourage. They eventually settled in Bukit Cina. It is believed that a significant number of them married into the local populace, creating the descendants now known as the Peranakan.[92] Owing to this supposed lineage, the Peranakan still use special honorifics: Baba for the men and Nyonya for the women.

- Indonesia

The Zheng Hoo Mosque in Surabaya.

Indonesian Chinese have established temples to Zheng He in Jakarta, Cirebon, Surabaya, and Semarang.[90]

In 1961, the Indonesian Islamic leader and scholar Hamka credited Zheng He with an important role in the development of Islam in Indonesia.[93] The Brunei Times credits Zheng He with building Chinese Muslim communities in Palembang and along the shores of Java, the Malay Peninsula, and the Philippines. These Muslims allegedly followed the Hanafi school in the Chinese language.[94] This Chinese Muslim community was led by Hajji Yan Ying Yu, who urged his followers to assimilate and take local names. The Chinese trader Sun Long even supposedly adopted the son of the king of Majapahit and his Chinese wife, a son who went on to become Raden Patah.[95] Amid this assimilation (and loss of contact with China itself), the Hanafi Islam became absorbed by the local Shafi'i school and the presence of distinctly ethnic Chinese Muslims dwindled to almost nothing.[96] The Malay Annals also record a number of Hanafi mosques – in Semarang and Ancol, for instance – were converted directly into temples of the Zheng He cult during the 1460s and '70s.[90]

Modern scholarship[]

In the 1950s, historians such as John Fairbank and Joseph Needham popularized the idea that after Zheng He's voyages China turned away from the seas due to the Haijin edict and was isolated from European technological advancements. Modern historians point out that Chinese maritime commerce did not totally stop after Zheng He, that Chinese ships continued to participate in Southeast Asian commerce until the 19th century, and that active Chinese trading with India and East Africa continued long after the time of Zheng. Moreover revisionist historians such as Jack Goldstone argue that the Zheng He voyages ended for practical reasons that did not reflect the technological level of China.[97] Although the Ming Dynasty did ban shipping with the Haijin edict, this was a policy of the Hongwu Emperor that long preceded Zheng He and the ban – so obviously disregarded by the Yongle Emperor – was eventually lifted entirely. However, the ban on maritime shipping did force countless numbers of people into smuggling and piracy. Neglect of the imperial navy and Nanjing dockyards after Zheng He's voyages left the coast highly vulnerable both to Japanese Wokou during the 16th century.[citation needed]

Richard von Glahn, a UCLA professor of Chinese history, commented that most treatments of Zheng He present him wrongly: they "offer counterfactual arguments" and "emphasize China's missed opportunity." This "narrative emphasizes the failure" instead of the accomplishments, despite his assertion that "Zheng He reshaped Asia." Glahn argues maritime history in the 15th century was essentially the Zheng He story and the effects of his voyages.[98]

Cultural influence[]

Despite the official neglect, the adventures of the fleet captured the imagination of some Chinese and novelizations of the voyages occurred, such as the Romance of the Three-Jeweled Eunuch in 1597.[89]

In modern times, interest in Zheng He revived substantially. In Vernor Vinge's 1999 science-fiction novel A Deepness in the Sky, a race of commercial traders in human space are named the Qeng Ho after the admiral. The expeditions featured prominently in Heather Terrell's 2005 novel The Map Thief. For the 600th anniversary of Zheng He's voyages in 2005, the China's CCTV produced a special television series Zheng He Xia Xiyang, starring Gallen Lo as Zheng He.

Relics[]

- Nanjing Temple of Mazu

Zheng He built the Tianfei Palace (天妃宫, Tiānfēigōng, lit. "Palace of the Celestial Wife"), a temple in honor of the goddess Mazu, in Nanjing after the fleet returned from its first western voyage in 1407.

- Taicang Stele

The "Deed of Foreign Connection and Exchange" (通番事跡) or "Tongfan Deed Stele" is located in the Tianfei Palace in Taicang, whence the expeditions first departed. The stele was submerged and lost, but has been rebuilt.

- Nanshan Stele

In order to thank the Celestial Wife for her blessings, Zheng He and his colleagues rebuilt the Tianfei Palace in Nanshan, Changle County, in Fujian province as well prior to departing on their last voyage. At the renovated temple, they raised a stele entitled "A Record of Tianfei Showing Her Presence and Power" (天妃靈應之記, Tiānfēi Líng Yīng zhī Jì), discussing their earlier voyages.[99]

- Sri Lankan Stele

The Galle Trilingual Inscription in Sri Lanka was discovered in the city of Galle in 1911 and is preserved at the National Museum of Colombo. The three languages used in the inscription were Chinese, Tamil and Persian. The inscription praises Buddha and describes the fleet's donations to the famous Buddhist Tenavarai Nayanar temple of Tondeswaram.[100][101]

- Tomb and Museum

Zheng He's tomb in Nanjing has been repaired and a small museum built next to it, although his body was buried at sea off the Malabar Coast near Calicut in western India.[102] However, his sword and other personal possessions were interred in a Muslim tomb inscribed in Arabic.

The tomb of Zheng He's assistant Hong Bao was recently unearthed in Nanjing, as well.

Commemoration[]

In the People's Republic of China, July 11 is Maritime Day (中国航海日, Zhōngguó Hánghǎi Rì) and is devoted to the memory of Zheng He's first voyage.

Gallery[]

See also[]

Notes[]

- ↑ It is located south of Kunming (Levathes 1996, 61).

- ↑ A chi is thought to vary between 10.5 to 12 inches (Dreyer 2007, 19).

- ↑ The Taizong Shilu 27 February 1424 entry reports that Zheng He was sent to deliver the seal, because the old seal was destroyed in a fire. The Xuanzong Shilu 17 September 1425 entry reports that Zhang Funama delivered a seal, because the old seal was destroyed in a fire. The later Mingshi compilers seem to have combined these accounts, remarking that Shi Jisun's succession was approved in 1424 and that a new seal was delivered in 1425, suggesting that only one seal was destroyed by fire. (Dreyer 2007, 96)

- ↑ Unnamed official who served as a Department Director under the Ministry of Works, who earlier had departed for Nanjing to supervise the renovation of government buildings and to reward the skilled workers (Dreyer 2007, 141).

References[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Dreyer 2007, 11.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Levathes 1996, 63.

- ↑ Liang Qihao. "Zuguo Da Hanghaijia Zheng He Zhuan". 1904. (Chinese)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Hui Chun Hing. "Huangming Zuxun and Zheng He’s Voyages to the Western Oceans". Journal of Chinese Studies, No. 51 (July, 2010). Accessed 17 Oct 2012.

- ↑ Levathes 1996, 61.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Mills 1970, 5.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Levathes 1996, 62.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Encyclopedia of China: The Essential Reference to China, Its History and Culture, p. 621. (2000) Dorothy Perkins. Roundtable Press, New York. ISBN 0-8160-2693-9 (hc); ISBN 0-8160-4374-4 (pbk).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ray 1987, 66.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Dreyer 2007, 148.

- ↑ Tan Ta Sen (2009). Cheng Ho and Islam in Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 171. ISBN 978-9812308375. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=vIUmU2ytmIIC&pg=PA171#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ↑ Gunn, Geoffrey C. (2011). History Without Borders: The Making of an Asian World Region, 1000-1800. Hong Kong University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-9888083343. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=E10tnvapZt0C&pg=PA117&dq=%22Zheng+he%22++mosques&hl=en&sa=X&ei=TUFIUtKzBPGv4QTrt4DIDw&ved=0CDkQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=%22Zheng%20he%22%20%20mosques&f=false.

- ↑ Lin (Chief Editor). Compiled by the Information Office of the People's Government of Fujian Province, ed. Zheng He's Voyages Down the Western Seas. China Intercontinental Press. p. 45.

- ↑ Shih-Shan Henry Tsai: Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle. University of Washington Press 2002, ISBN 978-0-295-98124-6, p. 38 (restricted online copy, p. 38, at Google Books)

- ↑ Chunjiang Fu, Choo Yen Foo, Yaw Hoong Siew: The great explorer Cheng Ho. Ambassador of peace. Asiapac Books Pte Ltd 2005, ISBN 978-981-229-410-4, p. 7-8 (restricted online copy, p. 8, at Google Books)

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Levathes 1996, 61–62.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Dreyer 2007, 12

- ↑ Levathes 1996, 62–63.

- ↑ Journal of Asian history, Volume 25. O. Harrassowitz.. 1991. p. 127. http://books.google.com/books?ei=MtPrTYuxL8Tk0QH-iNyrAQ&ct=result&id=CC5tAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 Levathes 1996, 58.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Dreyer 2007, 16.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Dreyer 2007, 18.

- ↑ Levathes 1996, 64.

- ↑ Levathes 1996, 64–66.

- ↑ Dreyer 2007, 12.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Dreyer 2007, 19.

- ↑ Dreyer 2007, 18–19.

- ↑ Dreyer 2007, 20

- ↑ Levathes 1996, 67.

- ↑ Dreyer 2007, 21.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Dreyer 2007, 22–23.

- ↑ Levathes 1996, 72–73.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Levathes 1996, 70.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Dreyer 2007, 21–22.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Levathes 1997, 72–73.

- ↑ Levathes 1996, 72.

- ↑ Historical documents have both spelling. See e.g. Xiang Da (向达), 《关于三宝太监下西洋的几种资料》("Regarding several kinds of historical materials on the expeditions of Eunuch Grand Director Sanbao to the Western Ocean"), in 《郑和研究百年论文选》(100 Years of Zheng He Studies: Selected Writings, ISBN 7-301-07154-X, p.10).

- ↑ Levathes 1996. 61-63.

- ↑ Dreyer 2007, 95 & 136.

- ↑ Dreyer 2007, 95.

- ↑ Dreyer 2007, 136–137.

- ↑ Duyvendak 1938, 388.

- ↑ Dreyer 2007, 95 & 136–137.

- ↑ Duyvendak 1938, 387.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 Dreyer 2007, 141–142.

- ↑ Mills 1970, 6.

- ↑ Mills 1970, 7.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 48.4 Chang, Kuei-Sheng. "The Maritime Scene in China at the Dawn of Great European Discoveries". Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 94, No. 3 (July–Sept., 1974), pp. 347-359. Retrieved 8 Oct 2012.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 Hui Chun Hing (2010). "Huangming zuxun and Zheng He’s Voyages to the Western Oceans (A Summary)". Institute of Chinese Studies. p. 85. http://web.ebscohost.com.library.esc.edu/ehost/detail?vid=3&hid=15&sid=687b5ea4-cc23-448c-87df-43a8d06508c6%40sessionmgr15&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=hia&AN=54558019. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ↑ Deng 2005, pg 13.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Shih-Shan Henry Tsai (2002). Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98124-6. http://books.google.com/?id=aU5hBMxNgWQC.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 "The Archaeological Researches into Zheng He's Treasure Ships". Travel-silkroad.com. http://www.travel-silkroad.com/english/marine/ZhengHe.htm. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ↑ Richard Gunde. "Zheng He's Voyages of Discovery". UCLA Asia Institute. http://www.international.ucla.edu/asia/news/article.asp?parentid=10387. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Tamura, Eileen H.; Linda K. Mention, Noren W. Lush, Francis K. C. Tsui, Warren Cohen (1997). China: Understanding Its Past. University of Hawaii Press. p. 70. ISBN 0-8248-1923-3. http://books.google.com/?id=O0TQ_Puz-w8C&pg=PA70&dq=Zheng+He+voyages.

- ↑ East Africa and its Invaders pg.37

- ↑ Cromer, Alan (1995). Uncommon Sense: The Heretical Nature of Science. Oxford University Press US. p. 117. ISBN 0-19-509636-3. http://books.google.com/?id=8cT2C87tb-sC&pg=PA117&dq=Zheng+He+voyages.

- ↑ Evan Hadingham is NOVA's Senior Science Editor. (1999-06-06). "NOVA | Ancient Chinese Explorers". Pbs.org. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ancient/ancient-chinese-explorers.html. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ↑ Duyvendak, J. J. L. (1939). "The True Dates of the Chinese Maritime Expeditions in the Early Fifteenth Century The True Dates of the Chinese Maritime Expeditions in the Early Fifteenth Century". p. 402. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4527170.

- ↑ Graffe, David A.. "Book Review of Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433". Journal of Military History. http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=6e77ebc7-6b4e-4827-bf59-1136f1b39b63%40sessionmgr14&vid=4&hid=10. Retrieved November 14, 2012.

- ↑ Deng 2005

- ↑ Ma Huan. Ying-yai Sheng-lan: The Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores.

- ↑ Bentley, Jerry H.; Ziegler, Herbert (2007). Traditions and Encounters: A Global Perspective on the Past. McGraw-Hill. p. 586. ISBN 0-07-340693-7.

- ↑ "Shipping News: Zheng He's Sexcentary". China Heritage Newsletter. http://www.chinaheritagenewsletter.org/articles.php?searchterm=002_zhenghe.inc&issue=002. Retrieved 4/12/2011.

- ↑ Yen Ch'ung-chien. Ch'u-yü chou-chih lu, Vol. III, ch. 8, 25. National Palace Museum (Peiping), 1930. Op. cit. in Chang, 1974.

- ↑ "The Seventh and Final Grand Voyage of the Treasure Fleet". Mariner.org. http://www.mariner.org/exploration/index.php?type=explorersection&id=57. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ↑ 66.00 66.01 66.02 66.03 66.04 66.05 66.06 66.07 66.08 66.09 66.10 66.11 66.12 66.13 66.14 66.15 66.16 66.17 66.18 66.19 66.20 66.21 66.22 66.23 66.24 66.25 66.26 66.27 66.28 66.29 66.30 66.31 66.32 66.33 66.34 66.35 66.36 66.37 66.38 66.39 66.40 66.41 66.42 66.43 66.44 66.45 66.46 66.47 66.48 66.49 Chan 1998, 233–236.

- ↑ Chinese accounts of Bengal, Banglapedia

- ↑ History of Sino-Bengal contacts

- ↑ 69.00 69.01 69.02 69.03 69.04 69.05 69.06 69.07 69.08 69.09 69.10 69.11 69.12 69.13 69.14 69.15 69.16 69.17 69.18 69.19 Dreyer 2007, 150–163.

- ↑ Tablet erected by Zheng He in Changle, Fujian Province, in 1432. Louise Levathes.

- ↑ Mei-Ling Hsu (1988). Chinese Marine Cartography: Sea Charts of Pre-Modern China. 40, pp96-112 (Imago Mundi ed.).

- ↑ Mills, J.V. (1970). Ma Huan Ying Yai Sheng Lan: The overall survey of the ocean shores. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Dreyer (2007): 82–95

- ↑ Dreyer (2007): 122–124

- ↑ "Briton charts Zheng He's course across globe". Chinaculture.org. http://www.chinaculture.org/gb/en_focus/2005-07/05/content_70352.htm. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ↑ Dreyer (2007)

- ↑ Science and Civilization in China, Joseph Needham, Volume 4, Section 3, pp.460-470

- ↑ Science and Civilization in China, Joseph Needham, Volume 4, Section 3, p.452

- ↑ Taiwan: A New History, Murray A. Rubinstein, page 49, M. E. Sharp, 1999, ISBN 1-56324-815-8

- ↑ Chinese discoverers dwarfed European travels, Tony Weaver, IOL, 11 November 2002.

- ↑ When China Ruled the Seas, Louise Levathes, p.80

- ↑ Church, Sally K. (2005). "Zheng He : An investigation into the plausibility of 450-ft treasure ships". pp. 1–43. http://www.chengho.org/downloads/SallyChurch.pdf

- ↑ Xin Yuanou: Guanyu Zheng He baochuan chidu de jishu fenxi (A Technical Analysis of the Size of Zheng He's Ships). Shanghai 2002, p.8

- ↑ The Archeological Researches into Zheng He's Treasure Ships, SilkRoad webpage.

- ↑ Wilson, Samuel M. "The Emperor's Giraffe", Natural History Vol. 101, No. 12, December 1992 [1]

- ↑ Rice, Xan (25 July 2010). "Chinese archaeologists' African quest for sunken ship of Ming admiral". The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/jul/25/kenya-china.

- ↑ "Could a rusty coin re-write Chinese-African history?". BBC News. 18 October 2010. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-11531398.

- ↑ "Zheng He'S Voyages To The Western Oceans 郑和下西洋". People.chinese.cn. http://people.chinese.cn/whcs/zhenghe/article/p2-5en.html. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 Blacks in Pre-Modern China, p. 121–122.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 90.3 90.4 90.5 Tan Ta Sen & al. Cheng Ho and Islam in Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2009. ISBN 9812308377, 9789812308375.

- ↑ Geoffery Wade lecture Nov, 2012

- ↑ Jin, Shaoqing (2005). Office of the People's Goverernment of Fujian Province. ed. Zheng He's Voyages down the Western Seas. Fujian, China: China Intercontinental Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-7-5085-0708-8. http://books.google.com/?id=QmpkR6l5MaMC&pg=PA58. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- ↑ Wang, Rosey Ma. "Chinese Muslims in Malaysia, History and Development".

- ↑ AQSHA, DARUL (July 13, 2010). "Zheng He and Islam in Southeast Asia". http://www.bt.com.bn/art-culture/2010/07/13/zheng-he-and-islam-southeast-asia. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ↑ Li Tong Cai. Indonesia – Legends and Facts. Op. Cit. "Wali Songo: The Nine Walis".

- ↑ Suryadinata Leo (2005). Admiral Zheng He & Southeast Asia. Singapore Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 981-230-329-4.[verification needed]

- ↑ Goldstone, Jack. "The Rise of the West - or Not? A Revision to Socio-economic History". http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/10/114.html.

- ↑ "Zheng He's Voyages of Discovery|UCLA center for Chinese Study|". International.ucla.edu. 20 April 2004. http://www.international.ucla.edu/china/article.asp?parentid=10387. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ↑ Fish, Robert J. "Primary Source: Zheng He Inscription". Univ. of Minnesota. Accessed 23 July 2009.

- ↑ Xinhua News Agency. "A Peaceful Mariner and Diplomat". 12 July 2005.

- ↑ Association for Asian Studies. Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368–1644, Vol. I. Columbia Univ. Press (New York), 1976.

- ↑ Levathes, Louise. When China Ruled The Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne 1405-1433, p. 172. Oxford Univ. Press (New York), 1996.

Bibliography[]

- Chan, Hok-lam (1998). "The Chien-wen, Yung-lo, Hung-hsi, and Hsüan-te reigns, 1399–1435". The Cambridge History of China, Volume 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521243322.

- Deng, Gang (2005). Chinese Maritime Activities and Socioeconomic Development, c. 2100 BC - 1900 AD. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29212-4.

- Dreyer, Edward L. (2007). Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming, 1405–1433 (Library of World Biography Series). Longman. ISBN 0-321-08443-8.

- Duyvendak, J.J.L. (1938). "The True Dates of the Chinese Maritime Expeditions in the Early Fifteenth Century". pp. 341–413. Digital object identifier:10.1163/156853238X00171. JSTOR 4527170.

- Levathes, Louise (1996). When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne, 1405–1433. Oxford University Press, trade paperback. ISBN 0-19-511207-5.

- Mills, J. V. G. (1970). Ying-yai Sheng-lan, The Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores (1433), translated from the Chinese text edited by Feng Ch'eng Chun with introduction, notes and appendices by J. V. G. Mills. White Lotus Press. Reprinted 1970, 1997. ISBN 974-8496-78-3.

- Ming-Yang, Dr Su. 2004 Seven Epic Voyages of Zheng He in Ming China (1405–1433)

- Ray, Haraprasad (1987). "An Analysis of the Chinese Maritime Voyages Into the Indian Ocean During Early Ming Dynasty and Their Raison d'Etre". pp. 65–87. Digital object identifier:10.1177/000944558702300107.

- Viviano, Frank (2005). "China's Great Armada." National Geographic, 208(1):28–53, July.

- Shipping News: Zheng He's Sexcentenary - China Heritage Newsletter, June 2005, ISSN 1833-8461. Published by the China Heritage Project of The Australian National University.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zheng He. |

- Zheng He - The Chinese Muslim Admiral

- Zheng He Journey to Arabia

- Zheng He 600th Anniversary

- BBC radio programme "Swimming Dragons".

- TIME magazine special feature on Zheng He (August 2001)

- Virtual exhibition from elibraryhub.com

- Ship imitates ancient vessel navigated by Zheng He at peopledaily.com (25 September 2006)

- Kahn, Joseph (2005). China Has an Ancient Mariner to Tell You About. The New York Times.

- Newsletter, in Chinese, on academic research on the Zheng He voyages

The original article can be found at Zheng He and the edit history here.