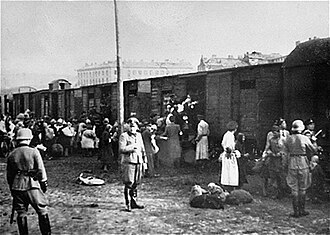

Polish Jews being loaded onto trains at Umschlagplatz in Warsaw Ghetto. The site today is preserved as a Polish national monument.

The Holocaust trains were railway transports run by German Nazis and their collaborators to forcibly deport interned Jews and other victims of the Holocaust to the German Nazi concentration and extermination camps.

Modern historians suggest that without the mass transportation of the railways, the scale of the Final Solution would not have been possible.[1]

Pre-war[]

Following the unsuccessful Évian Conference, in late 1938 at the invitation of a friend in the British Embassy in Prague, Czechoslovakia, 30-year-old clerk to the London Stock Exchange Nicholas Winton visited one of the rapidly expanding refugee camps for those fleeing the Nazis. At the Embassy's request, he set up an office at a dining room table in his hotel in Wenceslas Square, where he arranged train transport for children to Britain. On return to London, the British Government agreed to the shipment of the children on the conditions were that Winton had to pay the cost of the transport (arranged via Czech travel agency Cedok), pay a £50 bond, and arrange a foster family—at the time when few of the affected families could afford the cost.

In 18 months, Winton managed to arrange for 669 children to get out on eight trains, Prague to London (a small group of 15 were flown out via Sweden). The ninth and biggest train was to leave Prague on 3 September 1939 — the day Britain entered World War II. The train never left the station, and none of the 250 children on board were seen again. During the war, 15,000 Czech children were killed.[2]

The role of the railway in the Final Solution[]

Entrance, or so-called "death gate", to Auschwitz II-Birkenau, the extermination camp, in 2006

Within various phases of the Holocaust, the trains were used differently:

- After economic discrimination and separation, trains were used to concentrate the populations, either in ghettos, or—more often—to transport them to or concentration camps

- After concentration within ghettos, to transport the inmates to death camps

The scale of the extermination of members of groups targeted in the Final Solution was therefore only dependent on two factors:

- The capacity of the death camps to murder victims and process bodies

- The capacity of the railways to transport the condemned from the ghettos to the death camps

The most modern accurate numbers on the scale of the Final Solution still rely today partly on shipping records of the German railways.[3]

The advantage of using trains[]

To implement the Final Solution, the Nazis needed an efficient system for mass extermination. Although trains took valuable track space away, they sped up the scale and duration over which the extermination needed to take place. The enclosed nature of the railway wagons used also reduced the number and skill of troops required to transport the Jews, and allowed the Nazis to build and operate more efficient death camps to a larger scale, rather than wasting valuable production resources on bullets. Many of the Jews killed were from Eastern Europe where there were many trains that had already transported military goods to the Russian front, and would have been empty on their return to Germany were it not for the human cargo bound for the Holocaust.

There is "no word about those who committed the crimes", Hans-Rüdiger Minow, a spokesman for the Train of Commemoration, told The Jerusalem Post. He said 200,000 train employees were involved in the deportations and "10,000 to 20,000 were responsible for mass murders", but were never prosecuted.

Scale of the need for mass transportation[]

General map of deportation routes and camps

On 20 January 1942, after the Wannsee conference, the Nazis began to murder the Jews in large numbers. The mobile extermination squads were already conducting mass shootings of Jews in the areas of the occupied Soviet territories since 1941, and now Jews were either deported to then-empty ghettos including Riga, or to the death camps of Operation Reinhard: Treblinka, Belzec and Sobibór.

At Wannsee, the SS estimated that the "Final Solution" would ultimately annihilate 11 million European Jews; Nazi planners envisioned the inclusion of Jews living in neutral or non-occupied countries such as Ireland, Sweden, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. Deportations on this scale required the coordination of numerous German government ministries and state organisations, including the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), the Transport Ministry, and the Foreign Office. The RSHA coordinated and directed the deportations; the Transport Ministry organized train schedules; and the Foreign Office negotiated with German-allied states about handing over their Jews.[4]

Jews from Germany and German-occupied Europe were deported by rail to the extermination camps in occupied Poland, where they were systematically murdered. The Nazis disguised the Final Solution by referring to these deportations as "resettlement to the east". The victims were told they were being taken to labour camps, but in reality, from 1942, deportation for most Jews meant transit to extermination camps. During a telephone conversation in late 1942, Hitler's private secretary Martin Bormann admonished Heinrich Himmler, who was informing him that 50,000 Jews were already exterminated in a concentration camp in Poland. Bormann screamed: "They were not exterminated, only evacuated, evacuated, evacuated!", and slammed down the phone.

The journey[]

"Selection" on the Judenrampe, May–June 1944. To be sent to the right meant assignment to a work detail; to the left, the gas chambers. This image shows the arrival of Hungarian Jews from Carpatho-Ruthenia, many of them from the Berehov ghetto; the image was taken by Ernst Hofmann or Bernhard Walter of the SS. The main entrance, or "death gate", is visible in the background. Courtesy of Yad Vashem.[5]

The first trains operated on 16 October 1941, transporting Jews from central Germany to ghettos in the east.[6] Subsequently called "Sonderzüge" (special trains),[7] the trains had low priority for movement, and would proceed to the mainline after all other transport, inevitably extending shipping time scales.[7]

The trains consisted of formations of either third class passenger carriages,[8] but mainly freight cars or cattle cars—the latter were packed, according to SS regulations, with 50, but sometimes up to 150 occupants.[9] No food or water was provided, while the freight cars were only provided with a bucket latrine. A small barred window provided irregular ventilation, which sometimes resulted in deaths from either suffocation or the exposure to the elements.

Sometimes the Germans did not have enough cars to make it worth their while to do a major shipment of Jews to the camps, so the victims were stuck in a switching yard—"standing room only"—sometimes for days. At other times, the trains had to wait for more important military trains to pass.[9] An average transport took about four and a half days. The longest transport of the war, from Corfu, took 18 days. When the train got to the camps and the doors were opened, everyone was already dead.[1] The armed guards shot anyone trying to escape.

Due to cramped conditions, many deportees died in transit. On 18 August 1940, Waffen SS officer Kurt Gerstein later wrote in the Gerstein Report, that he had witnessed at Belzec: (the arrival of) "45 wagons with 6,700 people of whom 1,450 were already dead on arrival."[10] To avoid contamination between loads, at times the floor of the freight cars had a layer of quick lime, which burned the feet of the human cargo.

Once alighted, the remaining passengers were split into two groups. The old, the young, the sick, and the infirm were sent immediately to be killed, initially in gassing vans and later in the gas chambers. The Gerstein Report states:[10]

| “ | After the doors are closed... the diesel starts. Until this moment the people live in these 4 chambers, four times 750 people in 4 times 45 cubic metres! Again 25 minutes pass. Right, many are dead now. One can see that through the small window in which the electric light illuminates the chambers for a moment. After 28 minutes only a few are still alive. Finally, after 32 minutes, everyone is dead! | ” |

The rest were to put to work, frequently in the harshest conditions, which included the burial of victims in mass graves.[6]

The calculations[]

Typical freight steam locomotive used by the Deutsche Reichsbahn

Powered mainly by efficient freight steam locomotives, the trains were kept to a maximum of 55 freight cars.

The standard accommodation was a 10 metre long cattle freight wagon, although third class passenger carriages were also used where the SS wanted to keep up the "resettlement to work in the East" myth, particularly in the Netherlands and Belgium.

The standard SS manual covered such trains, suggesting a resultant loading ration per train of:

- 50 people in a freight car × 50 cars = 2,500 people in each train.

Since normally the trains were loaded to 150 to 200% capacity, this results in the following:

- 100 people in a freight car × 50 cars = 5,000 people in each train

Interior of a boxcar used to transport Jews and other victims during World War II. The boxcar is located inside the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

Of the estimated 6 million Jews exterminated during the Second World War, 2 million were murdered immediately by the second-rank military and political police, and mobile death squadrons of the Einsatzgruppen.

In total, over 1,600 trains were organised by the German Transport Ministry, and logged mainly by the Polish state railway company due to the majority of death camps being located in Poland.[11] Between 1941 and December 1944, the official date of closing of the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex, the transport/arrival timetable was of 1.5 trains per day:

- 50 freight cars × 50 prisoners per freight car × 1.5 trains/day × 1,066 days = 4,000,000 prisoners

On 20 January 1943, Himmler sent a letter to Reich Minister of Transport, Julius Dorpmüller: "need your help and support. If I am to wind things up quickly, I MUST HAVE MORE TRAINS."[12]

Payment[]

Most of the Jews were forced to pay for their own transportation, particularly where passenger carriages were used. This payment came in the form of direct money paid to the SS, in light of the "resettlement to work in the East" myth. Charged in the ghettos for accommodation, the Jews paid for a full one-way ticket,[13] while children under 10–12 years of age paid half price. Those who were running out of money in the ghetto were shipped to the East first, while those with some supplies of gold and cash were shipped last.

The SS also paid the German Transport Authority to pay the German Railways to transport Jews. The Reichsbahn was paid the equivalent of a third class railway ticket for every prisoner transported to the final destination:[7]

- 0.5 Pfennig × 8,000,000 prisoners × 600 km (pro media of voyage length) = 240 million Reichsmark

The Reichsbahn pocketed both this money and their share, after the SS fees, of the money paid by the transported.

Variations: Germany[]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The German State Railway (the Deutsche Reichsbahn)'s participation was crucial to the effective implementation of the "Final Solution of the Jewish Question". The DRB was paid to transport Jews and other victims of the Holocaust from thousands of towns and cities throughout Europe to meet their death in the Nazi concentration camp system. As well as transporting German Jews, DRB was responsible for co-ordinating transports on the rail networks of occupied territories and Germany's allies.

Variations across the rest of Europe[]

The characteristics of organized concentration and transportation of victims of the Holocaust varied by country.

Belgium[]

The Belgian response to the Final Solution effectively came in three parts: pre-war; occupation; and retreat. But at the end of the war, while many of the expatriate Jews who had sought refuge in Belgium before the war had been deported, only 6% of the native Belgian Jews had been taken from their country as part of the Final Solution.[14]

When Germany annexed Austria in the Anschluss in March 1938, and following the unsuccessful Évian Conference of June 1938, Belgium had in excess of 43,000 refugees within its borders, out of a total of 85,000 Jews within the whole country. The government ordered the Belgian Embassy in Vienna to stop issuing entry visas, and King Leopold III directly ordered the head of the Belgian State Security Service Robert de Foy to draw up lists of "suspect Belgians and foreigners".[15]

After German troops invaded Belgium on 10 May 1940, Gerd von Rundstedt was in charge of domestic affairs in Belgium. Yet when the Germans on 28 October 1940 forced all Jews to register with the police, the total number registered only came to 42,000.[14] After review of his lists by various collaborating national right-wing parties, de Foy was ordered by the Belgian authorities to round up the "unpatriotic" subjects. These Flemish-Nationalists, Communists, and non-Belgian citizens, most of them Jewish refugees from Germany and Poland. Hence de Foy's lists enabled Belgium to become the first Nazi country in occupied Western Europe to transport Jews to Auschwitz.[14]

These people were transported to France on so-called "phantom trains" the records for which were destroyed, but it is known that at least 3,000 were arrested under the plot in Antwerp alone. A phantom train on which Joris van Severen, leader of the pro-Belgian Fascist party was among 79 people deported is well recorded, as 21 people were killed by French soldiers at Abbeville.[16] Of the people deported on "phantom trains", most including the Belgian Jews were released by the Wehrmacht, the only Jews released by the Nazi German Army. 3,537 Jews holding German and Austrian passports were kept imprisoned at location, and were transported to Auschwitz for processing.

After this initial surge in repatriations and deportations, Hitler had chosen to put in place a military administration in Belgium, as opposed to a civilian administered government such as in the Netherlands. General Alexander von Falkenhausen was placed in military control of Belgium and Northern France, with SS Gruppenführer Eggert Reeder as his administrative deputy. Von Falkenhausen disliked the hardline Nazi position on the Jewish question, while King Leopold III had appointed Reeder Grand Cross of the Order of Leopold in the mid-1930s. Hence throughout his period of administration, Reeder co-operated with both von Falkenhausen and later Josef Grohé, together with the administrator of France Dr Werner Best, to try to apply the rules of the Hague Convention in their region, often against the wishes and instructions of their Wermacht and SS superiors.[17] In part they were aided by an on-going conflict between Himmler and Heydrich, which locally manifested itself as to who had what control over the still in place Belgian Police.

Reeder was directly responsible for the destruction of "Jewish influence" in the Belgian economy. But to ensure that all the Belgian people co-operated in the German occupation, Reeder negotiated an agreement to allow native Belgian Jews to remain in Belgium. Part of this was the non-enforcement of the Reich Main Security Office order for all Jews to be marked by wearing a yellow Star of David at all times, until Helmut Knochen's conference in Paris on 14 March 1942.[14] Although economic implementation led to mass unemployment of Belgian Jewish workers, especially in the diamond business, Reeder's efforts preserved full co-operation within Belgium and northern France during the German occupation. 2,250 of the unemployed Belgian Jews were sent to forced labour camps in Northern France (still under Reeder's control), in order to build the Atlantic Wall for Organisation Todt.[14]

Hence the Final Solution implementation in Belgium, centred on the Mechelen transit camp chosen because it was the hub of the Belgian railway system, never hit the centrally defined targets. Adolf Eichmann had set Theodor Dannecker targets of deported Jews as follows, starting 13 July 1940: 15,000 from the Netherlands; 10,000 from Belgium; and 100,000 from France.[14] On 5 December 1941, 83 Polish Jewish families were “repatriated" from Antwerp, while a larger number were sent in February–March 1942 to work in the textile factories of the Litzmannstadt ghetto. After that, stemming from orders issued post the Wannsee Conference, on 11 June 1942, SS Obersturnfuhrer Kurt Asche was ordered to deport 10,000 Jews from Belgium to Auschwitz, which he achieved by rounding-up non-Belgian Jews.[14] Native-born Belgian Jews were first noticed in the Auschwitz death camp, after 998 arrived from Mechelen on 5 August 1942, of which 744 were admitted into the camp.[14] After this point the number of non-resident Jews was low, and attempts at forced repatriation proved unsuccessful.

Original boxcar used for transport to concentration camps

Memorial Fort Breendonk

On 19 April 1943, Transport No.20 from Belgium left Mechelen with 1,631 Jews on board mainly from the Kazerne Dossin ghetto, heading for Auschwitz. Soon after leaving Mechelen, the driver stopped the train after seeing an emergency red light, actually three Belgian resistance fighters lead by Robert Maistriau. This was the first and only time during World War II that any Nazi transport carrying Jewish deportees was stopped. After a brief fire fight between the Nazi train guards and the three Resistance members - equipped only with one pistol between them - the train started again. During the fight, some deportees had escaped, and their escape resulted in others attempting to flee the now at speed train. After a second fire-fight that night during a scheduled stop, in total of the 233 people who attempted to escape from Transport No.20, 26 were shot that night, 89 were recaptured and 118 got away. When the train arrived at Auschitz, some sources claim that it was also unique in that although 70% of the women and girls were killed in the gas chambers immediately on arrival, all of the remaining women were sent to Block X of Birkenau for medical experimentation. Survivor Simon Gronowski later co-wrote a child's book to educate youngsters on the horrors of the Holocaust. Policeman John Aerts who helped him and others to evade recapture and return to Brussels was declared a "Righteous Gentile" by the Yad Vashem museum, Jerusalem. Of the three resistance workers: Robert Maistriau was arrested in March 1944, liberated from Bergen-Belsen in 1945, and lived until 2008; Youra Livschitz was later captured and executed; Jean Franklemon was arrested and sent to Sachsenhausen, liberated from there in May 1945, and died in 1977.[18]

The one attempt at the mass deportation from Belgium on 3 September 1943, proved a failure. After Wermacht raids, hundreds of Antwerp Jews were taken in furniture vans from their homes to the Jewish collection point at Mechelen. Soon afterwards, Reeder ordered their release at the direct insistence of Queen Elizabeth of Bavaria and Cardinal Jozef-Ernest van Roey, and the attempt was not repeated.[14] It was hence reported as "impossible" by local SS units charged with meeting Final Solution targets to find enough stateless and foreign Jews to fill another Auschwitz transport after 20 September 1943, though 1,800 Jews of various privileged categories were taken in 1944 to camps including Theresienstadt and Bergen-Belsen.[14]

After implementation of the Final Solution in Belgium, between August 1942 and July 1944, 28 trains transported more than 25,000 Jewish deportees to Auschwitz.[19]

After the War, De Foy resumed his position as head of the Belgian secret police. While the records about the persecution of the Antwerp Jews are intact, the documents about French-speaking cities with large Jewish communities including Charleroi and Liège, were claimed to have been purposely destroyed, even into the early 2000s.[16][20] At least 171 Jews of Charleroi and 312 Jews from Liege are known to have died in the Holocaust.

Both von Falkenhausen and Reeder were tried in Belgium in 1951, but only tried for deportation of 25,000 Jews from Belgium, and not their deaths in the concentration camps. Both were found guilty and sentenced to 12 years hard labour. But having already served their required one third sentence under Belgian law, on their return to West Germany, they were both immediately pardoned by Chancellor Konrad Adenauer.[14]

Bulgaria[]

On 22 February 1943 the Bulgarian government agreed to allow the Germans to deport 11,000 Jews from the former Serbian province of Vardar Banovina and Thrace (today's territories of Republic of Macedonia and Greece). Overcrowding conditions existed in the 20 trains that transported them over four days, requiring each train to stop daily to dump the bodies of those who died during the past day.[12] However, the Bulgarians were amongst the few nations in Europe to protect their Jewish community of 49,000 people, even though the country was allied to Nazi Germany.[21]

Czech Republic[]

Jews were interned and shipped from Theresienstadt, mainly to Birkenau.

The last train left Theresienstadt for Birkenau on 28 October 1944 with 2,038 Jews, of which 1,589 were immediately gassed.[22] Birkenau closed its gas chambers on 7 November 1944.

France[]

The SNCF under the Vichy Government played its part in the Final Solution, however reluctantly. In total, the Vichy government helped in the deportation of 76,000 Jews, although this number varies depending on the account, to German extermination camps; only 2,500 survived the war.[23][24]

Drancy, run until August 1944 by Alois Brunner,[25] served as the train transport hub for the Paris area and regions west and south thereof. By 3 February 1944, 67 trains had left from there for Birkenau.[22] Vittel served the northeast, closer to the German border from where all transports were taken over by German agents. By 23 June 1943, 50,000 Jews had been be deported from France, a pace that the Germans deemed too slow.[26] The last train from France left Drancy on 31 July 1944 with over 300 children.[22]

Greece[]

After the German occupation, an internment camp was set up in Athens to transport Jews to another internment camp at Thessaloniki, which served as the collection point for Jews from the Greek Islands.

In total, between March and August 1943, over 40,000 Jews were deported from Greece to Auschwitz-Birkenau,[19] including over 90% of Thessaloniki's 50,000 Jews. Of these, 5,000 Jews were deported from the regions of Thrace and Macedonia in northern Greece to Treblinka, where they were immediately gassed upon arrival.

Hungary[]

Hungary resisted the deportation of Hungarian Jews to Germany, but did deport 100,000 Jews in former Romanian territory of Transylvania, and Jews from occupied Yugoslavia.

After Hitler launched Operation Margarethe in March 1944, the discussions between him and Miklós Horthy came to a quick conclusion. On 29 April 1944 the first deportation to Birkenau took place, and the second on 30 April of 2,000 Jews. To allay fears of the remaining population estimated at 762,000, the SS had the deported write postcards to their family back home.[22]

On 25 May, German representative General Edmund Veesenmayer reported that 138,870 Jews had been deported in the past 10 days; on 31 May he reported that 60,000 more had been deported in the last six days, while the total for the past 16 days stood at 204,312.[22]

On 8 July 1944, due to international pressure by the Pope, the King of Sweden, and the Red Cross (all of whom had recently learned the extent of the Hungarian tragedy), the deportation of the Hungarian Jews stopped. In 70 days, 437,000 Hungarian Jews were deported—around 6,250 per day.[22]

In October 1944, following the coup d'état that put a Hungarist government in control, 50,000 of the remaining Jews were forced on a death march to Germany, digging anti-tank ditches on the roads westwards. A further 25,000 were saved in an "international ghetto" under Swedish protection engineered by Charles Lutz and Raoul Wallenberg. When the Soviet Army liberated Budapest on 17 January 1945, only 120,000 Hungarian Jews survived.[27]

Italy[]

Benito Mussolini resisted the deportation of Italian Jews to Germany. After the Allied landings on mainland Italy, and the 8 September 1943 Armistice with Italy, the Germans occupied northern Italy and shipped 8,000 Jews to Birkenau via mainly Austria, and also possibly via neutral Switzerland.

Between September 1943 and April 1944, at least 23,000 Italian soldiers were deported to work as slaves in German industry, while over 10,000 partisans were captured and deported during the same period to Birkenau. By 1944 there were over half a million Italians working for the Nazi war machine.[28]

Netherlands[]

In the Netherlands, Jews were concentrated in Amsterdam ghettos, before being moved for "resettlement in the East" to Westerbork, a transit camp in the north-east near the German border. Deportees from Amsterdam Muiderpoort station were unaware of their final destination or fate, as postcards were often thrown from moving trains.[29]

Between July 1942 and September 1944, almost every Tuesday a train left for the concentration camps Auschwitz-Birkenau, Sobibór, Bergen-Belsen and Theresienstadt. In the period from 1942 to 1945, a total of 107,000 people passed through the camp on a total of 93 outgoing trains: about 60,000 to Auschwitz and over 34,000 to Sobibor.[19]

Only 5,200 of the deportees survived, most of them in Theresienstadt or Bergen-Belsen, or liberated in Westerbork.[30] On 29 September 2005, Nederlandse Spoorwegen apologised for its role in the deportation of Jews.[31]

Poland[]

The Höfle Telegram lists the number of arrivals to the Aktion Reinhard Camps through 1942 (1,274,166)

Most of the Jews were transported by road to concentration camps, until the opening of the full five gas chambers at Auschwitz. The numerous train movements, both originating inside and outside occupied Poland and terminating at the various death camps, were tracked by the pre-war Polish railway company PKP, now in German possession, using IBM-supplied card-reading machines and railway software and made up 95% of IBM's business at the time.[11]

The Warsaw Ghetto was created by the German Nazis on 16 November 1940; eventually over 450,000 people cramped in an area meant for about 60,000. Shipments to the camps under Operation Reinhard were from the station at Umschlagplatz started on 22 July 1942 through to 12 September.[32] The Nazi record of Operation Reinhard lists the total number of killed, most of whom were transported by train, as follows:

| Location | Number and notes |

|---|---|

| Belzec | 246,922 deportees from within the General Government area alone, and a total of 600,000. Deportations to Belzec ended in December 1942 |

| Majdanek | 300,000 |

| Sobibor | 140,000 from Lublin, and 25,000 Jews from Lviv |

| Treblinka | 900,000 |

The Höfle Telegram lists the number of arrivals to the camps through 1942 as 1,274,166, while the total killed is estimated at 2 million.

On 18 August 1943, the last train ever to be sent to Treblinka camp left Białystok Ghetto—all survivors were sent to the gas chambers, after which the camp closed down.[26]

From 7 August 1944 the Nazis liquidated 68,000 Jews of the Łódź Ghetto, by then the largest remaining gathering of Jews in all of German occupied Europe. They were told by the SS that they were to be resettled; instead, over the next 23 days they were sent to Birkenau by train at the rate of 2,500 per day, with some of the crippled selected by Josef Mengele for his "medical experiments".[22]

Romania[]

Căile Ferate Române (Romanian Railways) have been involved in the transport of Jewish and Romani people to concentration camps in Romanian Old Kingdom, Bessarabia, northern Bukovina, and Transnistria.[33] In a notable example, after the Iasi pogrom events, Jews were forcibly loaded onto freight cars with planks hammered in place over the windows and traveled for days in unimaginable conditions. Many died and were gravely affected by lack of air, blistering heat, lack of water, food or medical attention. These veritable death trains arrived to their destinations Podu Iloaiei and Călăraşi with only one-fifth of their passengers alive.[33][34][35] No official apology was released yet by Căile Ferate Române for their role in the Holocaust in Romania.

[]

In October 1942, 770 Norwegian Jews were deported by boat to Hamburg and onwards by train to Auschwitz. The Danish resistance, on hearing a similar measure was to be attempted by the SS in Denmark, assisted in a mass rescue of the Danish Jews to neutral Sweden.[19]

Slovakia[]

On 9 September 1941, the parliament of "independent" Slovakia—a Nazi puppet state—ratified the Jewish Codex, a series of laws and regulations that stripped Slovakia's 80,000 Jews of their civil rights and all means of economic survival. The fascist Slovak leadership was so impatient to get rid of Jews that it paid the Nazis DM 500 in exchange for each expelled Jew and a promise that the deportees would never return to Slovakia. The decision by Slovakia to initiate and pay for the expulsion was unprecedented among the satellite states of Nazi Germany. They paid 40 millions RM to the SS.

Switzerland[]

Entrance to the St. Gotthard Tunnel

Although the Germans shipped most supplies to Italy through the Austrian Brenner Pass, based on the German-Italian-Swiss treaty of 1909 (to be denounced within ten years, by Article 374 of the 1919 Versailles Treaty),[36] Switzerland allowed Nazi Germany to ship certain non-strategic goods (specifically the treaty excluded soldiers and armaments) through the St. Gotthard Tunnel.

There exists substantial evidence that these shipments included Italian forced labour workers and possibly shipments of Jews in 1944, during the Nazi occupation of northern Italy, when a German train passed through Switzerland every 10 minutes. The need for the tunnel was complicated by the British Royal Air Force having bombed and disrupted services through the Brenner Pass, as well as a heavy snowfall in the winter of 1944/45.[28]

Of 43 trains that could be tracked down by the 1996 Bergier Commission, 39 went via Austria (Brenner, Tarvisio), one via France (Ventimiglia-Nice). The commission could not find any evidence that the other three passed through Switzerland. It is possible that the train could have been carrying dissidents back from concentration camps. Started in 1944, some repatriation trains went through Switzerland officially, organised by the Red Cross.[37][38]

1944 onwards[]

After the Soviet Army began making severe inroads into the Nazi land war gains in the East, and the Allies landed in Normandy in June, the number of trains and transported persons began to vary greatly.

By November 1944, with the closure of Birkenau and the advance of the Soviet Army, the death trains had ceased. Death marches also had the advantage of being able to use the forced labour to build defences.

Kastner train[]

In April 1944, for reasons that are still disputed, Nazi officials under the direction of SS officer Adolf Eichmann offered to sell the Zionist Aid and Rescue Committee (Vaada), of which Hungarian journalist and lawyer Rudolph Kastner was the de facto leader, exit visas for 600 Jews who held Palestinian immigration certificates,[39] in exchange for 6.5 million pengő (RM 4,000,000 or $1,600,000).[40]

The negotiations between the SS and the Vaada were expanded to include more Jews, and the Vaada compiled a list of ten categories of Jews they wanted to rescue, a list that included Orthodox Jews, Zionists, prominent Jews, orphans, refugees, Revisionists, and "paying persons".[40] The list also controversially included 388 people from Kastner's home town of Cluj.

Eventually the Kastner train transported 1,684 Jews from Nazi-controlled Hungary to Switzerland,[39] in exchange for 6.5 million pengő (RM 4,000,000 or $1,600,000).[40][41][42][43] Although Kastner was later criticised for putting his own family on the train, Hansi Brand, a member of the Vaada, testified at Eichmann's trial in Jerusalem in 1961 that Kastner had included his family to reassure the other passengers that the train was safe, and was not destined, as they feared, for Auschwitz.

1945[]

As the Soviet and Allied Armies made their final pushes, the Nazis transported some of the concentration camp survivors, either to other camps located further inside the collapsing Third Reich, or to border areas where they believed they could negotiate the release of captured Nazi Prisoners of War in return for "Exchange Jews" or those that were born outside the Nazi occupied territories.

Many of the inmates were transported via the infamous Death Marches, but among other transports three trains left Bergen-Belsen in April 1945 bound for Theresienstadt—all were liberated.[30]

The last recorded train is the one used to transport the women of the Flossenbürg March, where for three days in March 1945 the remaining survivors were crammed into cattle cars to await further transport. Only 200 of the original 1000 women survived the entire trip to Bergen-Belsen.[44]

Hungarian Gold Train[]

With the Soviet Army about 100 miles away from Hungary, on 7 March 1944, Hitler launched Operation Margarethe—the invasion of Hungary. The fascist government of Hungary issued a decree against the Jewish population, ordering them to "deposit" their gems, their golden jewels ornamented with gems, and all valuables made of gold, with the authorities. The jewels and other valuables of 800,000 Hungarian Jews were seized by the fascist government.

With the approach of Soviet and Allied forces, the government of Ferenc Szálasi had these valuables laden on a train consisting of 44 cars. This train was seized in May 1945 by U.S. occupation troops in Austria. The Hungarian escort pushed the train into the tunnel near Boeckstein, while the Americans took possession at the railway station of Werfen, where they found that the train also contained other valuables, e.g. oriental carpets, silver, furs, etc. While unloading the train to store the valuables, two lorries were seized in the French sector.

The goods were stored in two locations in Salzburg, with the valuables in one location and paintings in another. After goods were given to furnish American families locating to Europe, the remainder were repatriated for sale in America, where, in June 1948 they were sold at Parke-Bernet Galleries in New York. To date, of the scheduled 1,176 paintings on the gold train originally stored by the U.S. Army, only one has been repatriated.[45] On 30 September 2005, the U.S. Government reached agreement with the representatives of the Hungarian Jewish community to pay $25.5 million in compensation, with an additional $500k for the preservation of documents associated with the Gold Train, and to declassify any remaining documents related to the Gold Train.[46]

Modern-day legacy[]

There are still signs of the mass transportation system employed by the Nazis in the "Final Solution", as well as controversies surrounding the history.

Poland[]

The arrival point at Auschwitz is well preserved, although ceremonially cut-off from the main railway system.[47] In 1988 at the Umschlagplatz national monument, a stone sculpture resembling an open freight car was created by architect Hanna Szmalenberg and sculptor Wladyslaw Klamerus.

Germany[]

Federal Transport Minister Wolfgang Tiefensee proposed an exhibition by artist Jan Philipp Reemtsma on the railways' role in the deportation of 11,000 Jewish children to their deaths in Nazi concentration and extermination camps during World War II. The exhibit would travel around the country to various train stations. It was initially opposed by Hartmut Mehdorn, the head of Deutsche Bahn, because he considered the topic too serious for the proposed venue. However, Sonderzüge in den Tod opened on 23 January 2008, a date that coincides with the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz in 1945.[48]

France[]

In 2001, a lawsuit was filed against French government-owned rail company SNCF by Georges Lipietz, a Holocaust survivor, who was transported by SNCF to the Drancy internment camp in 1944.[49] Lipietz was held at the internment camp for several months before the camp was liberated.[50] After Lipietz's death the lawsuit was pursued by his family and in 2006 an administrative court in Toulouse ruled in favor of the Lipietz family. SNCF was ordered to pay 61,000 Euros in restitution. SNCF appealed the ruling at an administrative appeals court in Bordeaux, where in March 2007 the original ruling was overturned.[49][51] According to historian Michael Marrus the court in Bordeaux "declared the railway company had acted under the authority of the Vichy government and the German occupation" and as such could not be held independently liable.[52]

Following the Lipietz trial, SNCF's involvement in World War II became the subject of attention in the United States when SNCF explored bids on rail projects in Florida and California, and SNCF's partly owned subsidiary, Keolis Rail Services America bid on projects in Virginia and Maryland.[53] In 2010, Keolis placed a bid on a contract to operate the Brunswick and Camden lines of the MARC train in Maryland.[53] Following pressure from Holocaust survivors in Maryland, the state passed legislation in 2011 requiring companies bidding on the project to disclose their involvement in the Holocaust.[54][55] Keolis currently operates the Virginia Railway Express, a contract the company received in 2010.[53][54] In California, also in 2010, state lawmakers passed the Holocaust Survivor Responsibility Act. The bill, written to require companies to disclose their involvement in World War II,[56] was later vetoed by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger.[55][57]

While bidding on these rail contracts, SNCF was criticized for not formally acknowledging and apologizing for its involvement in World War II. In 2011, SNCF chairman Guillaume Pepy released a formal statement of regrets for the company's actions during World War II.[58][59][60] Some historians have expressed the opinion that SNCF has been unfairly targeted in the United States for their involvement in World War II. Human rights attorney Arno Klarsfeld has argued that the negative focus on SNCF was disrespectful to the French railway workers who lost their lives engaging in acts of resistance.[58] Marrus wrote in his 2011 essay that the company has taken responsibility for their actions and it is the company's willingness to open up their archives and acknowledge their involvement in the transportation of Holocaust victims that has led to the recent legal and legislative attention.[52]

In 1992, SNCF commissioned a report on its involvement in World War II. The company opened its archives to an independent historian, Christian Bachelier, whose report was released in French in 2000.[52][58][61] It was translated to English in 2010.[53] Between 2002 and 2004 SNCF helped fund an exhibit on deportation of Jewish children that was organized by Nazi hunter Serge Klarsfeld.[52] In 2011, SNCF helped set up a railway station outside of Paris to a Shoah Foundation for the creation of a memorial to honor Holocaust victims.[58]

Netherlands[]

Nederlandse Spoorwegen used its 29 September 2005 apology for its role in the "Final Solution" to launch an equal opportunities and anti-Discrimination policy, in part to be monitored by the Dutch council of Jews.[62]

Railway companies involved[]

See also[]

References[]

- Dawidowicz, Lucy S. (1986). The War Against the Jews, 1933–1945. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-02-908030-4.

- Hilberg, Raul (2003). The Destruction of the European Jews. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09557-0.

- Kranzler, David (2000). The Man who Stopped the Trains to Auschwitz: George Mantello, El Salvador, and Switzerland's Finest Hour. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-2873-0. Winner of the 1998 Egit Prize (Histadrut) for the Best Manuscript on the Holocaust.

- Gurdus, Luba Krugman (1978). The Death Train: A Personal Account of a Holocaust Survivor. New York: National Council on Art in Jewish Life. ISBN 0-89604-005-4.

- Hedi Enghelberg (1997 and subsequently revised). "The Trains of the Holocaust". enghelberg.com. http://www.enghelberg.com/ediciones/trains_holocaust.htm.

Notes[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Holocaust: The Trains

- ↑ Sir Nicholas Winton, Schindler Of Britain

- ↑ HOLOCAUST FAQ: Operation Reinhard: A Layman's Guide (2/2)

- ↑ German Railways and the Holocaust

- ↑ http://wWorld War I.yadvashem.org/exhibitions/album_auschwitz/home_auschwitz_album.html

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 ::::The Importance of World Peace: The Holocaust::::[dead link]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Approaches to Auschwitz—Richard L. Rubenstein, John K. Roth

- ↑ Recalling the Holocaust

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 http://www.jewishsf.com/content/2-0-/module/displaystory/story_id/25615/edition_id/498/format/html/displaystory.html

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Gerstein Report (English)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Edwin Black on IBM and the Holocaust

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 NAAF Holocaust Project Timeline 1943

- ↑ Fathoming the Holocaust—Ronald J. Berger

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 "The Destruction of the Jews of Belgium". Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team. http://www.holocaustresearchproject.org/nazioccupation/beligiumjews.html. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ↑ http://www.raphaelvishanu-world.at/Dec2003.html

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Belgian Authorities Destroy Holocaust Records | The Brussels Journal

- ↑ Dan Mikhman. Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans. Books.Google.co.uk. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=Gpk7P_mMFyUC&pg=PA213&lpg=PA213&dq=Eggert+Reeder&source=bl&ots=EDDgUDHfO4&sig=WdV0HjGnsuvbhHwT3WsNYQvtS2Y&hl=en&ei=W1-8TemcHdCxhQfz57i2BQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=6&ved=0CEQQ6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=Eggert%20Reeder&f=false. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ↑ "Escaping the train to Auschwitz". BBC News. 20 April 2013. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-22188075. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Deportations to Killing Centers

- ↑ Belgian Authorities Destroy Holocaust Records

- ↑ Beyond Hitler’s grasp: the heroic rescue of Bulgaria’s Jews. Holbrook, Mass.: Adams Media, 1998. ISBN 1-58062-060-4

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 NAAF Holocaust Project Timeline 1944

- ↑ J.-L. Einaudi and Maurice Rajsfus, Les silences de la police—16 July 1942 and 17 October 1961, L'Esprit frappeur, 2001, ISBN 2-84405-173-1

- ↑ Bremner, Charles (2008-11-01). "Vichy gets chance to lay ghost of Nazi past as France hosts summit". London: The Times. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article5057976.ece. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ↑ France condemned Brunner to death in absentia in 1954 for crimes against humanity. As of 2012, he is still wanted.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 NAAF Holocaust Project Timeline 1943 Continued

- ↑ The Man Who Stopped the Trains to Auschwitz, George Mantello, El Salvador, and Switzerland's Finest Hour

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 FRONTLINE: Switzerland: The Train

- ↑ 2007-05-01 Holocaust

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 BBC - Birmingham - Faith - The Last Train from Belsen

- ↑ "Like a slow train coming". Expatica.com. Archived from the original on 2007-12-11. http://web.archive.org/web/20071211164905/http://www.expatica.com/actual/article.asp?subchannel_id=19&story_id=23852.

- ↑ Holocaust Remembrance Day in Warsaw

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "What's New at Yad Vashem". Report of the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania. Yad Vashem. November 11, 2004. http://yad-vashem.org.il/about_yad/what_new/data_whats_new/report1.html. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ↑ Marcu Rozen (2006). "The Holocaust under the Antonescu government". Association of Romanian Jews Victims of the Holocaust (A.R.J.V.H.). http://www.survivors-romania.org/text_doc/the_holocaust_under_the_antonescu_government.htm. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ↑ "Holocaust in Podu Iloaiei, Romania". http://isurvived.org/2Postings/holocaust-Podul_Iloaiei-RO.html.

- ↑ The Avalon Project : The Versailles Treaty June 28, 1919

- ↑ Switzerland's Role in World War II

- ↑ Independent Commission of Experts, Switzerland—World War II. Bergier Commission for the Swiss Government

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Braham, p48; Bauer, p197.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Hilberg, Raul. The Destruction of the European Jews, Yale University Press, 2003, p. 903

- ↑ Braham, Randolph (2004): Rescue Operations in Hungary: Myths and Realities, East European Quarterly 38(2): 173–203.

- ↑ Bauer, Yehuda (1994): Jews for Sale?, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-05913-2.

- ↑ Bilsky, Leora (2004): Transformative Justice : Israeli Identity on Trial (Law, Meaning, and Violence), University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0-472-03037-X

- ↑ NAAF Holocaust Project Timeline: 1945

- ↑ The Mystery of the Hungarian "Gold Train"

- ↑ "Gold Train" Settlement Will Fund Services for Hungarian Holocaust Survivors; Objections, Exclusions Due August 1, 2005

- ↑ Auschwitz: A History by Sybille Steinbacher (Author), Shaun Whiteside (Translator) Pub: Penguin Books Ltd ISBN 0-14-102142-X

- ↑ > Nazi Death Train Exhibit Opens in Berlin

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 "French railways win WWII appeal". 27 March 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/6499227.stm. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ↑ CBC News (7 June 2006). "French railway must pay for transporting family to Nazis". http://www.cbc.ca/world/story/2006/06/07/france-pay.html. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ↑ Canellas, Claude (27 March 2007). "Court quashes SNCF Nazi deportations ruling". http://uk.reuters.com/article/2007/03/27/uk-france-holocaust-trial-idUKL2715470420070327. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 Marrus, Michael R. (2011). "Chapter 12 The Case of the French Railways and the Deportation of Jews in 1944". In Bankier, David; Michman, Dan. Holocaust and Justice. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-9-65308-353-0.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 Shaver, Katherine (7 July 2010). "Holocaust group faults VRE contract". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/07/06/AR2010070605169.html. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Zeitvogel, Karin (20 May 2011). "US governor signs Holocaust disclosure law". Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. https://archive.is/najyA. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Witte, Brian (19 May 2011). "Md. governor signs bill on company's WWII role". http://www.businessweek.com/ap/financialnews/D9NANRI81.htm. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ↑ Samuel, Henry (30 August 2010). "SNCF to open war archives to California". http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/france/7971894/SNCF-to-open-war-archives-to-California.html. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ↑ Weikel, Dan (2 October 2010). "Schwarzenegger vetoes bill requiring rail firms interested in train project to disclose WWII-era activities". http://articles.latimes.com/2010/oct/02/local/la-me-holocaust-20101002. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 58.3 Baume, Maïa De La (25 January 2011). "French Railway Formally Apologizes to Holocaust Victims". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/26/world/europe/26france.html. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ↑ Schofield, Hugh (13 November 2010). "SNCF apologises for role in WWII Jewish deportations". http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-11751246. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ↑ Ganley, Elaine (14 November 2010). "SNCF, French Railroad, Apologizes For Holocaust Role Before Florida Bid". http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/11/14/sncf-railroad-holocaust-apology-_n_783417.html. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ↑ "California set to force France's national rail service to reveal its Holocaust role as part of bid for $45m contract". 1 July 2010. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1291160/French-rail-operator-reveal-Holocaust-role-45bn-Californian-contract-bid.html#ixzz0sZ6U2128. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Dutch news - Expatica

- ↑ UK Treasury, Pears Foundation pledge £1.5m. for Holocaust education | Jerusalem Post

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Railway use for Holocaust. |

- Transports to Extinction: The Holocaust Deportation Database on the Yad Vashem website

- Photo slide show of the Holocaust, showing deportation trains

- The Hungarian Gold Train

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The original article can be found at Holocaust train and the edit history here.