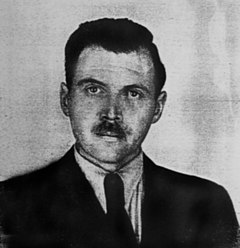

| Josef Mengele | |

|---|---|

| File:Josef Mengele.jpg | |

| Birth name | Josef Mengele |

| Nickname | Angel of Death (German: Todesengel) |

| Born | 16 March 1911 |

| Died | 7 February 1979 (aged 67) |

| Place of birth | Günzburg, Kingdom of Bavaria, German Empire |

| Place of death | Bertioga, São Paulo, Brazil |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1938—1945 |

| Rank |

|

| Service number |

NSDAP #5,574,974 SS #3,177,885 |

| Commands held | Human medical experimentation performed on prisoners at Auschwitz concentration camp, and selection of prisoners to be gassed at Auschwitz |

| Awards |

Iron Cross First Class Black Badge for the Wounded Medal for the Care of the German People |

| Signature |

|

Josef Mengele (German: [ˈjoːzɛf ˈmɛŋələ] (![]() listen); 16 March 1911 – 7 February 1979) was a German SS officer and a physician in the Nazi concentration camp Auschwitz. He qualified for scientific doctorates in Anthropology from Munich University and in Medicine from Frankfurt University. He became one of the more notorious characters to emerge from the III Reich in World War II as an SS medical officer who supervised the selection of victims of the Holocaust, determining who was to be killed and who was to temporarily become a forced laborer, and for performing bizarre and murderous human experiments on prisoners.

listen); 16 March 1911 – 7 February 1979) was a German SS officer and a physician in the Nazi concentration camp Auschwitz. He qualified for scientific doctorates in Anthropology from Munich University and in Medicine from Frankfurt University. He became one of the more notorious characters to emerge from the III Reich in World War II as an SS medical officer who supervised the selection of victims of the Holocaust, determining who was to be killed and who was to temporarily become a forced laborer, and for performing bizarre and murderous human experiments on prisoners.

Surviving the war, after a period of living incognito in Germany he fled to South America, where he evaded capture for the rest of his life, despite being hunted as a Nazi war criminal.

Early life and family[]

Josef Mengele was born the eldest of three children on 16 March 1911[1] to Karl and Walburga (Hupfauer) Mengele in Günzburg, Bavaria, Germany. His younger brothers were Karl Jr and Alois Mengele. Mengele's father was a founder of the Karl Mengele & Sons company, a company that produced farm machinery for milling, sawing, and baling.[2]

In 1935, Mengele earned a PhD in Anthropology from the University of Munich. In January 1937, at the Institute for Hereditary Biology and Racial Hygiene in Frankfurt, he became the assistant to Dr. Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer, who was a leading scientist mostly known for his research in genetics, with a particular interest in twins.[3] In addition, Mengele studied under Theodor Mollison and Eugen Fischer, who had been involved in medical experiments on the Herero tribe in South-West Africa, now Namibia.[4]

As an assistant to von Verschuer, Mengele's research focused on the genetic factors resulting in a cleft lip and palate, or a cleft chin.[5] His thesis on the subject earned him a cum laude doctorate. Had he continued his focus on academic matters, Mengele would have probably become a Professor.[6] His mentor and employer seemed suitably impressed by the young academic. He wrote a letter of recommendation which praised the reliability of Mengele and his ability to present "difficult intellectual problems" in a clear manner.[7] Robert Jay Lifton notes that Mengele's published works were "full of charts, diagrams, and photographs", with which the young man sought to bring science into the service of the "Nazi vision". In Lifton's view, the works did not deviate much from the scientific mainstream of the time, and would probably be seen as respectable scientific efforts even outside the borders of Nazi Germany.[7]

On 28 July 1939, Mengele married Irene Schönbein, whom he had met while studying in Leipzig. Their only son, Rolf, was born in 1944.[8] Five years after Mengele fled to Buenos Aires in 1949, his wife Irene divorced him. She continued to live in Germany with their son. On 25 July 1958, in Nueva Helvecia, Uruguay, Mengele married Martha Mengele, widow of his deceased brother Karl. Martha had arrived in Buenos Aires in 1956 with her son, Karl-Heinz Mengele.[9]

Military service[]

In 1937, Mengele joined the Nazi Party. In 1938, he received his medical degree and joined the SS. Mengele was conscripted into the army in 1940 and later volunteered for the medical service of the Waffen-SS, the combat arm of the SS, where he distinguished himself as a soldier. The III Reich declared war against the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941. Later that same month, Mengele was awarded the Iron Cross Second Class for service at the Ukrainian Front. In January 1942, whilst serving with the 5th SS Panzer Division Wiking he rescued two German soldiers from a burning tank and was awarded the Iron Cross First Class, as well as the Wound Badge in Black and the Medal for the "Care of the German People". After being medically evacuated from the Eastern Front with wounds sustained in action with the rank of Captain, he was, after recovery, transferred to the Race and Resettlement Office in Berlin. Whilst here Mengele resumed an association with his mentor, von Verschuer, who was at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Genetics and Eugenics in Berlin. Just before he was transferred to Auschwitz, Mengele was promoted to the rank of SS-Hauptsturmführer (Captain) in April 1943.[10][11]

Auschwitz[]

In May 1943, Mengele replaced another doctor who had fallen ill at the Nazi extermination camp Birkenau. On 24 May 1943, he became medical officer of Auschwitz-Birkenau's Zigeunerfamilienlager ("Gypsy Family Camp"). In August 1944, this camp was liquidated and all of its inmates were gassed.[12] Subsequently Mengele became Chief Medical Officer of the main infirmary camp at Birkenau. He was not the Chief Medical Officer of Auschwitz, though: his superior was SS-Standortarzt (garrison physician) Eduard Wirths.[13]

During his 21-month stay at Auschwitz, Mengele was referred to as "der weiße Engel" ("the White Angel") by camp inmates because when he stood on the platform inspecting and selecting new arrivals his white coat and white arms outstretched evoked the image of a white angel.[14] Mengele took turns with the other SS physicians at Auschwitz in meeting incoming prisoners at the camp, where it was determined who would be retained for work and who would be sent to the gas chambers immediately. He also appeared there frequently in search of twins for his experimentation. He would wade through the incoming prisoners, shouting "Zwillinge heraus!" ("Twins out!"), "Zwillinge heraustreten!" ("Twins step forward!") with, according to an assistant he recruited, "such a face that I would think he's mad"."Error: no |title= specified when using {{Cite web}}". Because he "brought such flamboyance and posturing to the selection", he was the individual best remembered for the process.[15] He drew a line on the wall of the children's block 150 centimetres (about 5 feet) from the floor and children whose heads could not reach the line were sent to the gas chambers.[16]

"He had a look that said 'I am the power,'" said one survivor. When it was reported that one block was infested with lice, Mengele ordered that the 750 women who lived inside the dormitories be gassed.[17]

Human experimentation[]

Block 10 – Medical experimentation block in Auschwitz

Mengele used Auschwitz as an opportunity to continue his research on heredity, using inmates for human experimentation. He was particularly interested in identical twins; they would be selected and placed in special barracks. He recruited Berthold Epstein, a Jewish pediatrician, and Miklós Nyiszli, a Hungarian Jewish pathologist, to assist with his experiments.

As a forced-labor prisoner under Mengele's direction, Epstein proposed a study into treatments of the disease called noma that was noted for particularly affecting children from the camp.[18] While the exact cause of noma remains uncertain, it is now known that it has a higher occurrence in children suffering from malnutrition and a lower immune system response. Many develop the disease shortly after contracting another illness such as measles or tuberculosis.[19]

Mengele took an interest in physical abnormalities discovered among the arrivals at the concentration camp. These included dwarfs, notably the Ovitz family – the children of a Romanian artist, seven of whom were dwarfs. Prior to their deportation, they toured in Eastern Europe as the Lilliput Troupe.

Mengele's experiments also included attempts to change eye colour by injecting chemicals into children's eyes, various amputations of limbs, and other such as kidney removal, without anaesthesia.[20] Rena Gelissen's account of her time in Auschwitz details certain experiments performed on female prisoners around October 1943. Mengele would experiment on the chosen girls, performing forced sterilization and electroconvulsive therapy. Most of the victims died, because of either the experiments or later infections.

Once Mengele's assistant rounded up fourteen pairs of Roma twins during the night. Mengele placed them on his polished marble dissection table and put them to sleep. He then injected chloroform into their hearts, killing them instantly. Mengele then began dissecting and meticulously noting each piece of the twins' bodies.[16]

At Auschwitz, Mengele did a number of studies on twins. After an experiment was over, the twins were usually killed and their bodies dissected. He supervised an operation by which two Roma children were sewn together to create conjoined twins; the hands of the children became badly infected where the veins had been resected; these twins soon died of an uncontrolled gangrene infection. In another "experiment", he connected a 7-year-old girl's urinary tract to her colon.[21]

Jewish twins kept alive to be used in Mengele's medical experiments. These children from Auschwitz were liberated by the Red Army in January 1945.

The subjects of Mengele's research were better fed and housed than ordinary prisoners and were, for the time being, safe from the gas chambers, although many experiments resulted in more painful deaths.[22] When visiting his child subjects, he introduced himself as "Uncle Mengele" and offered them sweets. Some survivors remember that despite his grim acts, he was also called "Mengele the Protector".[23]

Mengele also sought out pregnant women, on whom he would perform vivisections before sending them to the gas chambers.[24]

Former Auschwitz prisoner Alex Dekel has said:

I have never accepted the fact that Mengele himself believed he was doing serious work – not from the slipshod way he went about it. He was only exercising his power. Mengele ran a butcher shop – major surgeries were performed without anaesthesia. Once, I witnessed a stomach operation – Mengele was removing pieces from the stomach, but without any anaesthetic. Another time, it was a heart that was removed, again without anaesthesia. It was horrifying. Mengele was a doctor who became mad because of the power he was given. Nobody ever questioned him – why did this one die? Why did that one perish? The patients did not count. He professed to do what he did in the name of science, but it was a madness on his part.[25]

A former Auschwitz prisoner doctor has said:

He was capable of being so kind to the children, to have them become fond of him, to bring them sugar, to think of small details in their daily lives, and to do things we would genuinely admire.... And then, next to that,... the crematoria smoke, and these children, tomorrow or in a half-hour, he is going to send them there. Well, that is where the anomaly lay.[26]

The book Children of the Flames, by Lucette Matalon Lagnado and Sheila Cohn Dekel, chronicles Mengele's medical experimental activities on approximately 1,500 pairs of twins who passed through the Auschwitz death camp during World War II until its liberation at the end of the war. By the 1980s only 100 sets of these twins could be located. Many recalled his friendly manner towards them, and his gifts of chocolates. The older ones "recognized his kindness as a deception—yet another of his perverse experiments to test (our) mental endurance."[27] He would also kill them without hesitation, sometimes administering injections to the children or shooting them himself, and would dissect them immediately afterwards. On one evening alone he killed fourteen twins.[15]

In 1960, Hans Sedlmeier returned from Asuncion, Paraguay, with a statement from Mengele that said, "I personally have not killed, injured or caused bodily harm to anyone." Mengele repeatedly insisted that he had not committed any crime, and that instead he had become a victim of a great injustice.[28][29]

In the 1985 documentary The Search For Mengele Wolfram Bossert, who befriended Mengele in Brazil,[30] claimed that Mengele said, "I didn't make any experiments, it's all lies. The people volunteered because they got more food if they allowed me to take blood samples." He also claimed that Mengele assured him that he "deserves a statue from the Jews because as a doctor in the camp he saved many Jewish lives."[31]

After Auschwitz[]

The SS abandoned the Auschwitz camp on 27 January 1945, and Mengele transferred to Gross Rosen camp in Lower Silesia, again working as camp physician. Gross Rosen was dissolved at the end of February when the Red Army was close to taking it.[32] Mengele worked in other camps for a short time and, on 2 May, joined a Wehrmacht medical unit led by Hans Otto Kahler, his former colleague at the Institute of Hereditary Biology and Racial Hygiene in Bohemia. The unit hurried west to avoid being captured by the Soviets and were taken as prisoners of war by the Americans. Mengele, initially registered under his own name, was released in June 1945 with papers giving his name as "Fritz Hollmann".[citation needed] From July 1945 until May 1949, he worked as a farmhand in a small village near Rosenheim, Bavaria, staying in contact with his wife and his old friend Hans Sedlmeier, who arranged Mengele's escape to Argentina via Innsbruck, Sterzing, Meran, and Genoa. Mengele may have been assisted by the ODESSA network.[33]

In South America[]

Josef Mengele in 1956. Photo taken by a police photographer in Buenos Aires for Mengele's Argentine identification document.

In Buenos Aires, Mengele first worked in construction, but soon came in contact with influential Germans, who allowed him to live an affluent lifestyle in subsequent years. He also got to know other Nazis in Buenos Aires, such as Hans-Ulrich Rudel and Adolf Eichmann. In 1955, he bought a 50 percent share of Fadro Farm, a pharmaceutical company; the same year, he divorced his wife, Irene. Three years later, he married Martha Mengele in Uruguay, the widow of his younger brother, Karl Jr.; she then went to Argentina with her 14-year-old son, Dieter. Mengele lived with his family in a German-owned boarding house in the Buenos Aires suburb of Vicente Lopez from 1958 to 1960.[34] While living in Buenos Aires Mengele practised medicine though he became known for carrying out abortions—illegal in much of the world at the time, including Argentina. When a woman died from an abortion in his clinic he was brought before a judge, but was only briefly detained.[35]

Mengele was doing well in South America, yet he feared being captured, especially after news of Eichmann's capture and subsequent trial were revealed. Thus, he left Argentina in 1962 and moved to Paraguay after managing to get a Paraguayan passport in the name of "José Mengele".[34]

Shortly after the capture of Eichmann in May 1960 by the Israeli Mossad, Mengele was spotted at his home. Agents of the Mossad debated whether or not they should kidnap him as well. However, they still had Eichmann in a safe house inside Argentina, and determined that it would not be possible to conduct another operation at the same time. By the time Eichmann had been brought out of the country, Mengele had escaped to Paraguay.[36]

Isser Harel, Chief Executive of the Secret Services of Israel (1952–1963), personally presided over the successful effort to capture Eichmann in Buenos Aires. In his account of the operation, he reports no sightings of Mengele in 1960, but believes that they might have got him if they could have moved more quickly. When asked about the secondary target by the co-pilot who helped transport Eichmann at the time, he claims to have told him that "had it been possible to start the operation several weeks earlier, Mengele might also have been on the plane." They checked on the last known location for Mengele in Argentina, but he had apparently moved on just two weeks earlier.[37]

Mengele hoped that Paraguay would be safer for him, because dictator Alfredo Stroessner was of German descent and even recruited former Nazis to help the country develop. Among other locations in Paraguay, he lived on the outskirts of Hohenau, a German colony north of Encarnación in the department of Itapúa.

According to a senior Mossad man, Israel had received reports that Mengele was in Brazil, but they kept this information to themselves. The Six-Day War in 1967 forced them to concentrate their resources on operations related to the war. But after the war, Israel decided to open an embassy in Asunción, Paraguay – perhaps an ideal base from which to pursue Mengele. But Benjamin Weiser Varon, Israeli ambassador from 1968 to 1972, was "not given any instructions by the foreign office on Mengele of any kind. It wasn't even mentioned."

"I must confess I was not so eager to find Mengele. He presented a dilemma. Israel had less of a claim for his extradition than Germany. He was, after all, a German citizen who had committed his crimes in the name of the Third Reich. None of his victims were Israeli—Israel came into existence only several years later."[38]

Mengele's home in Hohenau, Paraguay

The same year, Mengele moved to Nova Europa, about 200 km (120 mi) outside São Paulo, where he lived with Hungarian refugees Geza and Gitta Stammer, working as manager of their farm. In the seclusion of his Brazilian hideaway Mengele was safe. In 1974, when his relationship with the Stammer family was coming to an end, Hans-Ulrich Rudel and Wolfgang Gerhard discussed relocating Mengele to Bolivia where he could spend time with Klaus Barbie, but Mengele rejected this proposal. Instead, he lived in a bungalow in a suburb of São Paulo for the last years of his life. In 1977, his only son Rolf, never having known his father before, visited him there and found an unrepentant Nazi who claimed that he "had never personally harmed anyone in his whole life".[33]

Mengele's health had been deteriorating for years, and he died on 7 February 1979, in Bertioga, Brazil, where he accidentally drowned, or possibly suffered a stroke, while swimming in the Atlantic. He was buried in Embu das Artes under the name "Wolfgang Gerhard", whose ID card he had used since 1976.[39]

Mengele showed little regret or remorse for his crimes, and expressed in a letter his astonishment and disgust over the remorseful position taken by Hitler's chief architect and Minister of Armaments, Albert Speer.[40]

Argentine historian Jorge Camarasa speculated in his 2008 biography that Mengele, under the alias Rudolph Weiss, continued his human experimentation in South America, and as a result of these experiments, a municipality in Brazil, Cândido Godói, has a very high birthrate of twin children: one in five pregnancies, with a substantial amount of the population looking Nordic.[41] His theory was rejected by Brazilian scientists who had studied twins living in the area; they suggested genetic factors within that community as a more likely explanation.[42][43]

Manhunt[]

Mengele was listed on the Allies' list of war criminals as early as 1944. His name was mentioned in the Nuremberg trials several times, but Allied forces were convinced that Mengele was dead, which was also claimed by Irene and the family in Günzburg. In 1959, suspicions had grown that he was still alive, given his divorce from Irene in 1955 and his marriage to Martha in 1958. An arrest warrant was issued by the West German authorities. Subsequently, West German attorneys such as Fritz Bauer, Israel's Mossad, and private investigators such as Simon Wiesenthal and Beate Klarsfeld followed the trail of the "Angel of Death". The last confirmed sightings of Mengele placed him in Paraguay, and it was believed that he was still hiding there, allegedly protected by flying ace Hans-Ulrich Rudel and possibly even by the dictator President Alfredo Stroessner. Mengele sightings were reported all over the world, but they turned out to be false.

In 1985, the West German police raided Hans Sedlmeier's house in Günzburg and seized address books, letters, and papers hinting at the grave in Embu. The remains of "Wolfgang Gerhard" were exhumed on 6 June 1985 and identified as Mengele's with high probability by forensic experts from UNICAMP. Rolf Mengele issued a statement saying that he "had no doubt it was the remains of his father".[33] Everything was kept quiet "to protect those who knew him in South America", Rolf said. In 1992, a DNA test confirmed Mengele's identity. He had evaded capture for 34 years.

After the exhumation, the São Paulo Institute for Forensic Medicine stored his remains and attempted to repatriate them to the remaining Mengele family members, but the family rejected them. The bones have been stored at the São Paulo Institute for Forensic Medicine ever since.[44] According to the Find A Grave database, Mengele's body has been cremated. Since the family has not claimed the ashes, they remain in the custody of unnamed Brazilian officials.[45]

In the 21st century[]

On 17 September 2007, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum released photographs taken from a photo album of Auschwitz staff, which contained eight photographs of Mengele. According to museum officials, these eight photos of Mengele are the first authenticated pictures of him at Auschwitz.[46]

In February 2010, Mengele's diary, kept from 1960 until his death in 1979, which included letters sent to Rolf and Wolfgang Gerhard, was sold at auction in Connecticut by Alexander Autographs for an estimated $200,000 (£130,000). According to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA), the buyer was an East Coast Jewish philanthropist who wished to remain anonymous. The auction triggered protests amongst some Holocaust survivors, who described it as "a cynical act of exploitation aimed at profiting from the writings of one of the most heinous Nazi criminals."[47] The previous owner, who acquired the diary in Brazil, is said to be close to the Mengele family.[48]

Pseudonyms[]

- Wolfgang Gerhard

- Fritz Hollmann

- José Mengele[49]

- Helmut Gregor[i][49]

- Rudolph Weiss

- Dr. Fausto Rindón[49]

- S. Josi Alvers Aspiazu [sic][49]

Summary of SS career[]

- SS number: 317,885

- Nazi Party number: 5,574,974

- Primary Positions: WVHA, Medical Physician (Auschwitz Concentration Camp)

- Waffen-SS Service:

- Medical Staff Officer, Waffen-SS Medical Inspectorate (1940)

- Medical Officer, Pioneer Battalion No. 5, 5th SS Panzer Division Wiking (1941–1943)

- Medical Officer, Battalion "Ost", 3rd SS Division Totenkopf (1943)

Dates of Rank

- SS-Schütze: May 1938[50]

- SS-Hauptscharführer der Reserve (d.R.): 1939

- SS-Untersturmführer d.R.: 1 August 1940

- SS-Obersturmführer d.R.: 30 January 1942

- SS-Hauptsturmführer d.R.: 20 April 1943

Awards

- Iron Cross (First and Second Class)

- War Merit Cross (Second Class with Swords)

- Eastern Front Medal

- Wound Badge (Black)

- Social Welfare Decoration

- German Sports Badge (Bronze)

- Honour Chevron for the Old Guard[51]

Writings[]

- Racial-Morphological Examinations of the Anterior Portion of the Lower Jaw in Four Racial Groups. His anthropological dissertation, completed in 1935 and first published in 1937. In this work Mengele sought to demonstrate that there were structural differences in the lower jaws of individuals from different ethnic groups, and that racial distinctions could be made based on these differences. The four "races" of the title were Egyptians, Melanesians, brachycephalic (short-skulled) Europeans such as the Dinarics, and dolichocephalic (long-skulled) Europeans such as the Nordics.[7]

- Genealogical Studies in the Cases of Cleft Lip-Jaw-Palate (1938), his medical dissertation. Studying the "irregularly dominant hereditary process" resulting in these "abnormalities", Mengele contacted genealogical research on families which demonstrated these traits in multiple generations. The work also included notes on "additional anomalies and deformities" found in these family lines.[7]

- Hereditary Transmission of Fistulae Auris. A journal article focusing on Fistula Auris, which is an abnormal opening in the cartilage of the human ear. The article is essentially a "case report" on the condition as a hereditary trait. Mengele took note that individuals who have this trait tend to also have dimples on their chin. Mengele himself is said to share these genetic traits.[7]

In film[]

Mengele is depicted in the 1978 fictional drama The Boys From Brazil, derived from the 1976 novel of the same name by Ira Levin.

The 2013 fictional Argentinian film The German Doctor, based on Lucía Puenzo's novel Wakolda also portrays him.[52][53]

See also[]

- Nazi eugenics

- Solahütte, Nazi resort frequented by Mengele and among the only places where he was photographed in uniform.

- Unit 731, Imperial Japan's biological and chemical warfare research unit, also notorious for their human experimentation

- Villa Baviera

- People

- John Charles Cutler, M.D. – an American senior surgeon who infected people with syphilis

- Shirō Ishii, a Japanese microbiologist leader of Japan's infamous Unit 731

Sources[]

- Allison, Kirk C. (2011). "The Routledge History of the Holocaust". In Friedman, Jonathan C.. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1136870606. http://books.google.gr/books?id=vsrJLASVC3QC&pg=PA52&dq=Mengele+%22cleft+lip%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=RXVNUtauLofJswawo4GYAw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Mengele%20%22cleft%20lip%22&f=false.

- Lifton, Robert J. (2000 (reprint of a 1986 work)). "The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide". Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465049059. http://books.google.gr/books?id=bv8IAqVh8EAC&pg=PA339&dq=Mengele+%22cleft+lip%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=RXVNUtauLofJswawo4GYAw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Mengele%20%22cleft%20lip%22&f=false.

- Weindling, Paul (2008). "A Companion to Genethics, Blackwell Companions to Philosophy, Vol. 45". In Burley, Justine; Harris, John. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0470756379. http://books.google.gr/books?id=FzuwRwb--X4C&pg=PA53&dq=Mengele+%22cleft+lip%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=RXVNUtauLofJswawo4GYAw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Mengele%20%22cleft%20lip%22&f=false.

Notes and references[]

- ↑ Stefan Kanfer and Peter Carls. "The Life and Crimes of a Nazi Doctor". People. http://www.people.com/people/archive/article/0,,20091148,00.html.

- ↑ "The Gunzburg Clan" Time, June 24, 1985

- ↑ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Josef Mengele.” Holocaust Encyclopedia.[1]

- ↑ Allan D Cooper, The Geography of Genocide, page 153, University Press of America, 2009

- ↑ Weindling (2008), p. 53

- ↑ Allison (2011), p. 52

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Lifton (2000), p. 339-340

- ↑ "Son Says Mengele Showed No Remorse". Chicago Tribune. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1985-06-19/news/8502090107_1_rolf-mengele-father-auschwitz. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ "Mengele's Wife Found, Paper Says". Chicago Tribune. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1985-03-12/news/8501140167_1_martha-mengele-karl-mengele-nazi-doctor-josef-mengele. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ "Josef Mengele". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/article.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10007060. Retrieved March 23, 2008.

- ↑ "Dr. Josef Mengele, ruthless Nazi concentration camp doctor – The Crime Library – Crime Library on". Trutv.com. http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/serial_killers/history/mengele/3b.html. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ↑ "Genocide Remembrance Day of the Roma and Sinti". http://en.auschwitz.org/m/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1026&Itemid=7.

- ↑ "Eduard Wirths". Wsg-hist.uni-linz.ac.at. http://www.wsg-hist.uni-linz.ac.at/Auschwitz/HTML/Wirths.html. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ↑ "Josef Mengele – factfile". The Daily Telegraph. January 23, 2009. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/southamerica/brazil/4319715/Josef-Mengele-factfile.html. Retrieved January 27, 2012.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "What Made This Man? Mengele". The New York Times. 21 July 1985. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. https://archive.is/XZYe. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Bülow, Louis. "Josef Mengele, Angel of Death". http://www.auschwitz.dk/Mengele.htm. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- ↑ "Mengele – The Final Account". New York City, United States: History Channel. 12 July 2008.

- ↑ "Page 296-297". Holocaust-history.org. 21 July 2005. http://www.holocaust-history.org/lifton/LiftonT296.shtml. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ↑ "German article at". Shoa.de. http://www.shoa.de/p_josef_mengele.html. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ↑ Schult, Christoph (10 Dec 2009). "Dr. Mengele's Victim: Why One Auschwitz Survivor Avoided Doctors for 65 Years". Der Spiegel. http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/dr-mengele-s-victim-why-one-auschwitz-survivor-avoided-doctors-for-65-years-a-666327.html. Retrieved 11 Mar 2013.

- ↑ Eva Mozes-Kor. "Mengele Twins and Human Experimentation: A Personal Account". In The Nazi Doctors and the Nuremberg Code. p. 57

- ↑ Nyiszli, Miklos (1 September 1993). Auschwitz: A Doctor's Eyewitness Account. Arcade Publishing. ISBN 1-55970-202-8.

- ↑ Lagnado, Lucette Matalon; Sheila Cohn Dekel (1991). Children of the Flames. ISBN 0-688-09695-6.

- ↑ Brozan, Nadine. Out of Death, a Zest for Life. New York Times, 15 November 1982

- ↑ "Dr. Josef Mengele, ruthless Nazi concentration camp doctor - The Crime Library on truTV.com". Crimelibrary.com. http://www.crimelibrary.com/serial_killers/history/mengele/research_5.html. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ↑ Robert Jay Lifton. The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide, Basic Books, 1986, p. 337

- ↑ Children of the Flames; Dr. Josef Mengele and the Untold Story of the Twins of Auschwitz by Lucette Matalon Lagnado and Sheila Cohn Dekel. 'Mengele; the Complete Story' by Gerald Posner and John Ware.[2]

- ↑ Alice Siegert. (9 June 1985). "'Mengele Family Keeps Uneasy Silence'". United Press International..[3]

- ↑ New York Times, 14 June 1985; Baltimore Sun, 14 June 1985

- ↑ "Mengele letters reveal life ended in pain and poverty". The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2004/nov/23/secondworldwar. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Mengele denied performing ghastly experiments on anybody". The Search For Mengele. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b9hFBLQphOg. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- ↑ Chicago Tribune Magazine "How Nazi war criminal Josef Mengele cheated justice for 34 years" by Gerald L. Posner and John Ware, 18 May 1986.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Völklein, Ulrich (1999). Josef Mengele: Der Arzt von Auschwitz. Steidl. ISBN 3-88243-685-9.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Harel, Isser (2 June 1975). The House on Garibaldi Street. Viking Press. p. 194. ISBN 0-670-38028-8.

- ↑ Nathaniel C. Nash (11 February 1992). "Mengele an Abortionist, Argentine Files Suggest". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E0CEFDF1E39F932A25751C0A964958260&scp=1&sq=Mengele&st=nyt. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ↑ Israeli Mossad let Nazi Mengele get away[dead link] Replacement link: USA Today (accessible as of 12 May 2010). This news item comes from AP, but their archive fails to find it as if it never was. USA Today in Web Archive: "Blocked site error" [4]. Attempting to archive it in WebCite: "WebCite is currently under maintenance We will be back up soon." (12 May 2010)

- ↑ Harel, Isser (1975). The house on Garibaldi Street: the first full account of the capture of Adolf Eichmann. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-38028-8.

- ↑ "How Nazi war criminal Josef Mengele cheated justice for 34 years – Signs of the Times News". sott.net. http://www.sott.net/articles/show/150662-How-Nazi-war-criminal-Josef-Mengele-cheated-justice-for-34-years. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ↑ Blumenthal, Ralph (22 July 1985). "Scientists Decide Brazil Skeleton Is Josef Mengele.". New York Times. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F20C14FF3A5D0C718EDDAF0894DD484D81&scp=5&sq=Josef+Mengele&st=nyt. Retrieved 21 March 2008. "American, Brazilian and West German scientists announced jointly today that a skeleton recently exhumed from a graveyard near here was unquestionably that of Dr. Josef Mengele. A separate report by American experts concluded that the bones were those of the long-sought Nazi death-camp doctor 'within a reasonable scientific certainty.' ..."

- ↑ Erich Wiedemann and Jens Glüsing (29 November 2004). "Angel of Death" Diary Shows No Regrets". Der Spiegel. http://www.spiegel.de/international/spiegel/0,1518,330311-2,00.html. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ↑ Evans, Nick (21 January 2009). "Nazi angel of death Josef Mengele 'created twin town in Brazil'". The Daily Telegraph. UK. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/southamerica/brazil/4307262/Nazi-angel-of-death-Josef-Mengele-created-twin-town-in-Brazil.html. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ↑ Linda Geddes: Nazi 'Angel of Death' not responsible for town of twins New Scientist online, 27 January 2009

- ↑ "National Geographic Explorer: Nazi Mystery: Twins from Brazil". National Geographic Explorer: Nazi Mystery: Twins from Brazil. National Geographic Exlorer. http://channel.nationalgeographic.com/series/explorer/4087/Overview. Retrieved The first air date: 29 November 2009.

- ↑ By MARLISE SIMONS, Special to the New York Times (17 March 1988). "Remains of Mengele Rest Uneasily in Brazil". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=940DE0D7153CF937A25750C0A96E948260. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ↑ Josef Mengele at Find a Grave

- ↑ "Collections | Auschwitz through the lens of the SS: Photos of Nazi leadership at the camp". Ushmm.org. 21 June 1944. http://www.ushmm.org/research/collections/highlights/auschwitz/. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ↑ , "Survivor's grandson buys Mengele diary", 3 February 2010, Retrieved 28 September 2010

- ↑ Hall, Allan. "Nazi doctor Josef Mengele's diary up for sale", The Daily Telegraph, 1 February 2010, Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 Christian Zentner, Friedemann Bedürftig. The Encyclopedia of the Third Reich, p. 586. Macmillan, New York, 1991. ISBN 0-02-897502-2

- ↑ Mengele's enlisted service is mentioned on only a single document of his official SS file. His entry date into the SS is stated to have occurred in the spring of 1938, and by the date of his commissioning in 1940, Mengele was serving as an SS-First Sergeant in the Waffen-SS Reserve (Source: SS Service Record of Josef Mengele, National Archives, College Park)

- ↑ Mengele's SS service record indicates this decoration, even though Mengele was not a Nazi Party or SS member prior to 1933, which was a primary requirement for the Old Guard Chevron. (Source: SS Service Record of Josef Mengele, National Archives, College Park)

- ↑ ""Wakolda", the film about Mengele in Argentina, chosen as Oscar precandidate" (in Spanish). Yahoo! News Spain. 27 September 2013. http://es.noticias.yahoo.com/wakolda-filme-mengele-argentina-elegido-precandidato-%C3%B3scar-172746605.html. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ↑ "Oscars: Argentina Nominates 'Wakolda' for Foreign Language Oscar". Hollywood Reporter. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/oscars-argentina-nominates-wakolda-foreign-638296. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

Further reading[]

- Harel, Isser (1975). The House on Garibaldi Street: the First Full Account of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-38028-8.

- Lieberman, Herbert A. (1978). The Climate of Hell. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-82236-5.

- Astor, Gerald (1986). Last Nazi: Life and Times of Doctor Joseph Mengele. Weidenfeld & N. ISBN 0-297-78853-1.

- Ware, John; Posner, Gerald (1986). Mengele: The Complete Story. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-050598-5.

- Levin, Ira (1991). Boys from Brazil, The. London: Bantam. ISBN 0-553-29004-5.

- Lagnado, Lucette (1992). Children of the Flames: Dr. Josef Mengele and the Untold Story of the Twins of Auschwitz. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140169317

- Nyiszli, Miklos (1993). Auschwitz: A Doctor’s Eyewitness Account. New York: Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1611450118

External links[]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Josef Mengele.  Quotations related to Josef Mengele at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Josef Mengele at Wikiquote- "In the Matter of Josef Mengele A Report to the Attorney General of the United States." United States Department of Justice. October 1992.

- Josef Mengele at Find a Grave

- A timeline of Mengele's life

- Chicago Tribune Magazine: "How Nazi war criminal Josef Mengele cheated justice for 34 years" by Gerald Posner and John Ware

- Declassified U.S. CIA information on Mengele and other NSDAP war criminals

- "Skeletons in the Closet of German Science," Deutsche Welle September 18, 2005

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum: Auschwitz through the lens of the SS. Recently discovered photographs of SS leadership, among them the first authenticated pictures of Mengele at Auschwitz

Camps, ghettos and operationsCamps Mass shootings Ghettos Other atrocities Perpetrators, participants, organizations, and collaboratorsMajor perpetrators OrganizersCamp commandGas chamber executionersGhetto commandPersonnel Camp guardsBy campOrganizations Collaborators JewishEstonian, Latvian,

Lithuanian, Belarusian

and UkrainianOther nationalitiesResistance: Judenrat, victims, documentation and technicalOrganizations Uprisings Leaders Judenrat Victim lists GhettosCampsDocumentation Nazi sourcesWitness accountsConcealmentTechnical and logistics Aftermath, trials and commemorationAftermath Trials West German trialsPolish, East German, and Soviet trialsMemorials Righteous among the Nations

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The original article can be found at Josef Mengele and the edit history here.