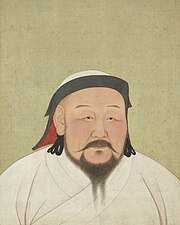

| Kublai Khan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Portrait of Kublai Khan during the Yuan era. | |

| Khagan of the Mongol Empire Founder of the Yuan Dynasty Emperor of China | |

| Preceded by | Möngke Khan |

| Succeeded by | Temür Khan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 23, 1215 |

| Died | February 18, 1294 (aged 78) Dadu (Khanbaliq) |

| Spouse(s) | Tegulen, Chabi, Nambui |

Kublai Khan (/ˈkuːblə ˈkɑːn/; Mongolian language: Хубилай хаан, Xubilaĭ xaan; Middle Mongolian language: Qubilai Qaγan, "King Qubilai"; September 23, 1215 – February 18, 1294),[1][2] born Kublai (Mongolian language: Хубилай, Xubilaĭ; Middle Mongolian language: Qubilai; Chinese: 忽必烈; pinyin: Hūbìliè; also spelled Khubilai) and also known by the temple name Shizu (Chinese: 元世祖; pinyin: Yuán Shìzǔ; Wade–Giles: Yüan Shih-tsu), was the fifth Khagan (Great Khan) of the Ikh Mongol Uls (Mongol Empire), reigning from 1260 to 1294, and the founder of the Yuan Dynasty in China.

Kublai was the second son of Tolui and Sorghaghtani Beki, and a grandson of Genghis Khan. He succeeded his older brother Möngke as Khagan in 1260, but had to defeat his younger brother Ariq Böke in a succession war lasting till 1264. This episode marked the beginning of disunity in the empire.[3] Kublai's real power was limited to China and Mongolia, though as Khagan he still had influence in the Ilkhanate and, to a far lesser degree, in the Golden Horde.[4][5][6] If one counts the Mongol Empire at that time as a whole, his realm reached from the Pacific to the Black Sea, from Siberia to modern day Afghanistan – one fifth of the world's inhabited land area.[7]

In 1271, Kublai established the Yuan Dynasty, which ruled over present-day Mongolia, China, Korea, and some adjacent areas, and assumed the role of Emperor of China. By 1279, the Yuan forces had overcome the last resistance of the Southern Song Dynasty, and Kublai became the first non-Chinese Emperor to conquer all of China. He was also the only Mongol khan after 1260 to win new conquests.[8]

The summer garden of Kublai Khan at Xanadu is the subject of Samuel Taylor Coleridge's 1797 poem Kubla Khan. This poem and Marco Polo's earlier book brought Kublai and his achievements to the attention of a wider audience, and today Kublai is a well-known historical figure.

Early years[]

Kublai was the second son of Tolui and Sorghaghtani Beki. As his grandfather Genghis Khan advised, Sorghaghtani chose a Buddhist Tangut woman as her son's nurse, whom Kublai later honored highly. On his way home after the conquest of the Khwarizmian Empire, Genghis Khan performed a ceremony on his grandsons Möngke and Kublai after their first hunt in 1224 near the Ili River.[9] Kublai was nine years old and with his eldest brother killed a rabbit and an antelope. His grandfather smeared fat from killed animals onto Kublai's middle finger in accordance with a Mongol tradition.

After the Mongol–Jin War, in 1236, Ögedei gave Hebei Province (attached with 80,000 households) to the family of Tolui, who died in 1232. Kublai received an estate of his own, which included 10,000 households. Because he was inexperienced, Kublai allowed local officials free rein. Corruption amongst his officials and aggressive taxation caused large numbers of Chinese peasants to flee, which led to a decline in tax revenues. Kublai quickly came to his appanage in Hebei and ordered reforms. Sorghaghtani sent new officials to help him and tax laws were revised. Thanks to those efforts, many of the people who fled returned.

The most prominent, and arguably the most influential component of Kublai Khan's early life was his study and strong attraction to contemporary Chinese culture. Kublai invited Haiyun, the leading Buddhist monk in North China, to his ordo in Mongolia. When he met Haiyun in Karakorum in 1242, Kublai asked him about the philosophy of Buddhism. Haiyun named Kublai's son, who was born in 1243, Zhenjin (True Gold in English).[10] Haiyun also introduced Kublai to the former Taoist and now Buddhist monk, Liu Bingzhong. Liu was a painter, calligrapher, poet and mathematician, and became Kublai's advisor when Haiyun returned to his temple in modern Beijing.[11] Kublai soon added the Shanxi scholar Zhao Bi to his entourage. Kublai employed people of other nationalities as well, for he was keen to balance local and imperial interests, Mongol and Turk.

Kublai's victory in North China[]

Portrait of young Kublai by Anige, a Nepali artist in Kublai's court

In 1251, Kublai's eldest brother Möngke became Khan of the Mongol Empire, and Khwarizmian Mahmud Yalavach and Kublai were sent to China. Kublai received the viceroyalty over North China and moved his ordo to central Inner Mongolia. During his years as viceroy, Kublai managed his territory well, boosted the agricultural output of Henan and increased social welfare spendings after receiving Xi'an. These acts received great acclaim from the Chinese warlords and were essential to the building of the Yuan Dynasty. In 1252 Kublai criticized Mahmud Yalavach, who was never highly valued by his Chinese associates, over his cavalier execution of suspects during a judicial review and Zhao Bi attacked him for his presumptuous attitude toward the throne. Möngke dismissed Mahmud Yalavach, which met with resistance from Chinese Confucian-trained officials.[12]

In 1253, Kublai was ordered to attack Yunnan, and he asked the Kingdom of Dali to submit. The ruling Gao family resisted and killed Mongol envoys. The Mongols divided their forces into three. One wing rode eastward into the Sichuan basin. The second column under Subutai's son Uryankhadai took a difficult route into the mountains of western Sichuan.[13] Kublai went south over the grasslands and met up with the first column. While Uryankhadai travelled along the lakeside from the north, Kublai took the capital city of Dali and spared the residents despite the slaying of his ambassadors. Duan Xingzhi, the last king of Dali, was appointed by Möngke Khan as the first local ruler; Duan accepted the stationing of a pacification commissioner there.[14] After Kublai's departure, unrest broke out among certain factions. In 1255 and 1256, Duan Xingzhi was presented at court, where he offered Mengu, the Yuan Emperor Xienzhong, maps of Yunnan and counsels about the vanquishing of the tribes who had not yet surrendered. Duan then led a considerable army to serve as guides and vanguards for the Mongolian army. By the end of 1256, Uryankhadai had completely pacified Yunnan.[15]

Kublai was attracted by the abilities of Tibetan monks as healers. In 1253 he made Drogön Chögyal Phagpa, of the Sakya order, a member of his entourage. Phagpa bestowed on Kublai and his wife, Chabi (Chabui), a Tantric Buddhist initiation. Kublai appointed Uyghur Lian Xixian (1231–1280) the head his pacification commission in 1254. Some officials, who were jealous of Kublai's success, said that he was getting above himself and dreaming of having his own empire by competing with Möngke's capital Karakorum (Хархорум). The Great Khan Möngke sent two tax inspectors, Alamdar (Ariq Böke's close friend and governor in North China) and Liu Taiping, to audit Kublai's officials in 1257. They found fault, listed 142 breaches of regulations, accused Chinese officials and executed some of them, and Kublai's new pacification commission was abolished.[16] Kublai sent a two-man embassy with his wives and then appealed in person to Möngke, who publicly forgave his younger brother and reconciled with him.

The Taoists had obtained their wealth and status by seizing Buddhist temples. Möngke repeatedly demanded that the Taoists cease their denigration of Buddhism and ordered Kublai to end the clerical strife between the Taoists and Buddhists in his territory.[17] Kublai called a conference of Taoist and Buddhist leaders in early 1258. At the conference, the Taoist claim was officially refuted and Kublai forcibly converted 237 Taoist temples to Buddhism and destroyed all copies of the Taoist texts.[18][19][20][21] Kublai Khan and the Yuan dynasty clearly favored Buddhism, while his counterparts in the Chagatai Khanate, the Golden Horde and the Ilkhanate later converted to Islam at various times in history - Berke of the Golden Horde being the only Moslem during Kublai's era (his successor remained a pagan).

In 1258, Möngke put Kublai in command of the Eastern Army and summoned him to assist with an attack on Sichuan. As he was suffering from gout, Kublai was allowed to stay home, but he moved to assist Möngke anyway. Before Kublai arrived in 1259, word reached him that Möngke had died. Kublai decided to keep the death of his brother secret and continued the attack on Wuhan, near the Yangtze River. While Kublai's force besieged Wuchang, Uryankhadai joined him.[citation needed]

The Song Dynasty minister Jia Sidao secretly approached Kublai to propose terms. He offered an annual tribute of 200,000 taels of silver and 200,000 bolts of silk, in exchange for Mongol agreement to the Yangtze River as the frontier between the states.[22] Kublai at first declined, but later reached a peace agreement with Jia Sidao.

Enthronement and civil war[]

Kublai received a message from his wife that his younger brother Ariq Böke had been raising troops, and returned north to the Mongolian plains.[23] Before he reached Mongolia, he learned that Ariq Böke had held a kurultai (Mongol great council), at the capital Karakorum, which had named him Great Khan with the support of most of Genghis Khan's descendants. Kublai and the fourth brother, the Il-Khan Hulagu opposed this. Kublai's Chinese staff encouraged Kublai to ascend the throne, and almost all of the senior princes in North China and Manchuria supported his candidacy.[24] Upon returning to his own territories, Kublai summoned his own kurultai. Few members of the royal family supported Kublai's claims to the title, though the small number of attendees included representatives of all the Borjigin lines except that of Jochi. This kurultai proclaimed Kublai Great Khan, on April 15, 1260, despite Ariq Böke's apparently legal claim.

Kublai Khan was chosen by his many supporters to become the next Great Khan at the Grand Kurultai in the year 1260. (a Mughal painting)

This led to warfare between Kublai and Ariq Böke, which resulted in the destruction of the Mongolian capital at Karakorum. In Shaanxi and Sichuan, Möngke's army supported Ariq Böke. Kublai dispatched Lian Xixian to Shaanxi and Sichuan, where they executed Ariq Böke's civil administrator Liu Taiping and won over several wavering generals.[25] To secure the southern front, Kublai attempted a diplomatic resolution and sent envoys to Hangzhou, but Jia broke his promise and arrested them.[26] Kublai sent Abishqa as new khan to the Chagatai Khanate. Ariq Böke captured Abishqa, two other princes and 100 men and had his own man, Alghu, crowned khan of Chagatai's territory. In the first armed clash between Ariq Böke and Kublai, Ariq Böke lost and his commander Alamdar was killed at the battle. In revenge, Ariq Böke had Abishqa executed. Kublai cut off supplies of food to Karakorum with the support of his cousin Kadan, son of Ögedei Khan. Karakorum quickly fell to Kublai's large army, but following Kublai's departure it was temporarily re-taken by Ariq Böke in 1261. Yizhou governor Li Tan revolted against Mongol rule in February 1262 and Kublai ordered his Chancellor Shi Tianze and Shi Shu to attack Li Tan. The two armies crushed Li Tan's revolt in just a few months and Li Tan was executed. These armies also executed Wang Wentong, Li Tan's father-in-law, who had been appointed the Chief Administrator of the Zhongshusheng ("Department of Central Governing") early in Kublai's reign and became one of Kublai's most trusted Han Chinese officials. The incident instilled in Kublai a distrust of ethnic Hans. After becoming emperor, Kublai banned granting the titles of and tithes to Han Chinese warlords.[citation needed]

Chagatayid Khan Alghu, who had been appointed by Ariq Böke, declared his allegiance to Kublai and defeated a punitive expedition sent by Ariq Böke in 1262. The Ilkhan Hulagu also sided with Kublai and criticized Ariq Böke. Ariq Böke surrendered to Kublai at Xanadu on August 21, 1264. The rulers of the western khanates acknowledged Kublai's victory and rule in Mongolia.[27] When Kublai summoned them to a new kurultai, Alghu Khan demanded recognition of his illegal position from Kublai in return. Despite tensions between them, both Hulagu and Berke, khan of the Golden Horde, at first accepted Kublai's invitation.[28][29] However, they soon declined to attend the kurultai. Kublai pardoned Ariq Böke, although he executed Ariq Böke's chief supporters.

Reign[]

Great Khan of the Mongols[]

The suspicious deaths of three Jochid princes in Hulagu's service, the Siege of Baghdad and unequal distribution of war spoils strained the Ilkhanate's relations with the Golden Horde. In 1262, Hulagu's complete purge of the Jochid troops and support for Kublai in his conflict with Ariq Böke brought open war with the Golden Horde. Kublai reinforced Hulagu with 30,000 young Mongols in order to stabilize the political crises in the western regions of the Mongol Empire.[30] When Hulagu died on February 8, 1264, Berke marched to cross near Tiflis to conquer the Ilkhanate but died on the way. Within a few months of these deaths, Alghu Khan of the Chagatai Khanate also died. In the new official version of his family's history, Kublai refused to write Berke's name as the khan of the Golden Horde because of Berke's support for Ariq Böke and wars with Hulagu; however, Jochi's family was fully recognized as legitimate family members.[31]

Kublai Khan named Abaqa as the new Ilkhan (obedient khan) and nominated Batu's grandson Möngke Temür for the throne of Sarai, the capital of the Golden Horde.[32][33] The Kublaids in the east retained suzerainty over the Ilkhans until the end of their regime.[34][35] Kublai also sent his protege Baraq to overthrow the court of Oirat Orghana, the empress of the Chagatai Khanate, who put her young son Mubarak Shah on the throne in 1265, without Kublai's permission after her husband's death. Ögedeid prince Kaidu declined to personally attend the court of Kublai. Kublai instigated Baraq to attack Kaidu. Baraq began to expand his realm northward; he seized power in 1266 and fought Kaidu and the Golden Horde. He also pushed out Great Khan's overseer from the Tarim Basin. When Kaidu and Möngke Timur together defeated Kublai, Baraq joined an alliance with the House of Ögedei and the Golden Horde against Kublai in the east and Abagha in the west. Meanwhile, Möngke Temür avoided any direct military expedition against Kublai's realm. The Golden Horde promised Kublai their assistance to defeat Kaidu whom Möngke Temür called the rebel.[36] This was apparently due to the conflict between Kaidu and Möngke Temür over the agreement they made at the Talas kurultai. The armies of Mongol Persia defeated Baraq's invading forces in 1269. When Baraq died the next year, Kaidu took control of the Chagatai Khanate and recovered his alliance with Möngke Temür.

Meanwhile, Kublai tried to stabilize his control over Korea by mobilizing another Mongol invasion after he appointed Wonjong (r. 1260–1274) as the new Goryeo king in 1259 in Kanghwa. Kublai forced two rulers of the Golden Horde and the Ilkhanate to call a truce with each other in 1270 despite the Golden Horde's interests in the Middle East and Caucasia.[37] Kublai called two Iraqi siege engineers from the Ilkhanate in order to destroy the fortresses of Song China. After the fall of Xiangyang in 1273, Kublai's commanders, Aju and Liu Zheng, proposed a final campaign against the Song Dynasty, and Kublai made Bayan the supreme commander.[38] Kublai ordered Möngke Temür to revise the second census of the Golden Horde to provide resources and men for his conquest of China.[39] The census took place in all parts of the Golden Horde, including Smolensk and Vitebsk in 1274–75. The Khans also sent Nogai to the Balkans to strengthen Mongol influence there.[40]

Kublai renamed the Mongol regime in China Dai Yuan in 1271, and sought to sinicize his image as Emperor of China in order to win control of millions of Chinese people. When he moved his headquarters to Khanbaliq, also called Dadu, at modern-day Beijing, there was an uprising in the old capital Karakorum that he barely contained. Kublai's actions were condemned by traditionalists and his critics still accused him of being too closely tied to Chinese culture. They sent a message to him: "The old customs of our Empire are not those of the Chinese laws... What will happen to the old customs?"[41][42] Kaidu attracted the other elites of Mongol Khanates, declaring himself to be a legitimate heir to the throne instead of Kublai, who had turned away from the ways of Genghis Khan.[43][44] Defections from Kublai's Dynasty swelled the Ögedeids' forces.

Painting of Kublai Khan on a hunting expedition, by Chinese court artist Liu Guandao, c. 1280.

The Song imperial family surrendered to the Yuan in 1276, making the Mongols the first non-Chinese people to conquer all of China. Three years later, Yuan marines crushed the last of the Song loyalists. The Song Empress Dowager and her grandson, Zhao Xian, were then settled in Khanbalic where they were given tax-free property, and Kublai's wife Chabi took a personal interest in their well-being. However, Kublai later had Zhao sent away to become a monk to Zhangye. Kublai succeeded in building a powerful Empire, created an academy, offices, trade ports and canals and sponsored science and the arts. The record of the Mongols lists 20,166 public schools created during Kublai's reign.[45] Having achieved real or nominal dominion over much of Eurasia, and having successfully conquered China, Kublai was in a position to look beyond China.[46] However, Kublai's costly invasions of Burma, Annam, Sakhalin and Champa secured only the vassal status of those countries. The Mongol invasions of Japan (1274 and 1280) and Java (1293) failed. At the same time, Kublai's nephew Ilkhan Abagha tried to form a grand alliance of the Mongols and the Western European powers to defeat the Mamluks in Syria and North Africa that constantly invaded the Mongol dominions. Abagha and Kublai focused mostly on foreign alliances, and opened trade routes. Khagan Kublai dined with a large court every day, and met with many ambassadors, foreign merchants.

Kublai's son Nomukhan and his generals occupied Almaliq from 1266 to 1276. In 1277, a group of Genghisid princes under Möngke's son Shiregi rebelled, kidnapped Kublai's two sons and his general Antong and handed them over to Kaidu and Möngke Temür. The latter was still allied with Kaidu who fashioned an alliance with him in 1269, although Möngke Temür had promised Kublai his military support to protect Kublai from the Ögedeids.[47] Kublai's armies suppressed the rebellion and strengthened the Yuan garrisons in Mongolia and the Ili River basin. However, Kaidu took control over Almaliq.

Extract of the letter of Arghun to Philip IV of France, in the Mongolian script, dated 1289. French National Archives.

In 1279–80, Kublai decreed death for those who performed Islamic-Jewish slaughtering of cattle, which offended Mongolian custom.[48] When the Ahmad Teguder seized the throne of the Ilkhanate in 1282, attempting to make peace with the Mamluks, Abaqa's old Mongols under prince Arghun appealed to Kublai. After the execution of Ahmad, Kublai confirmed Arghun's coronation and awarded his commander in chief Buqa the title of .[citation needed]

Kublai's niece, Kelmish, who married a Khunggirat general of the Golden Horde, was powerful enough to have Kublai's sons Nomuqan and Kokhchu returned. Three leaders of the Jochids, Töde Möngke, Konchi, and Nogai, agreed to release two princes.[49] The court of the Golden Horde returned the princes as a peace overture to the Yuan Dynasty in 1282 and induced Kaidu to release Kublai's general. Konchi, khan of White Horde, established friendly relations with the Yuan and the Ilkhanate, and as a reward received luxury gifts and grain from Kublai.[50] Despite political disagreement between contending branches of the family over the office of Khagan, the economic and commercial system continued.[51][52][53][54]

Emperor of the Yuan Dynasty[]

The Yuan Dynasty, c. 1294

Kublai Khan considered China as his main base; he realized within a decade of his enthronement as Great Khan that he needed to concentrate on governing China.[55] From the beginning of his reign, he adopted Chinese political and cultural models and worked to minimize the influences of regional lords, who had held immense power before and during the Song Dynasty. Kublai heavily relied on his Chinese advisers until about 1276. He had many Han Chinese advisers, such as Liu Bingzhong and Xu Heng, and employed many Uyghur Turks, some of whom were resident commissioners running Chinese districts.[56]

Kublai also appointed Phagspa Lama his state preceptor (Guoshi), giving him power over all of the empire's Buddhist monks. In 1270, after Phagspa created the Square script, he was promoted to imperial preceptor. Kublai established the Supreme Control Commission under Phagspa to administer affairs of Tibetan and Chinese monks. During Phagspa's absence in Tibet, the Tibetan monk Sangha rose to high office and had the office renamed the Commission for Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs.[57][58] In 1286, Tibetan Sangha became the dynasty's chief fiscal officer. However, their corruption later embittered Kublai, after which Kublai relied wholly on younger Mongol aristocrats. Antong of the Jalayir, and Bayan of the Baarin served as grand councillors from 1265, and Oz-temur of the Arulad headed the censorate. Borokhula's descendant, Ochicher, headed a kheshig (Mongolian imperial guard) and the palace provision commission.

In the eighth year of Zhiyuan (1271), Kublai officially created the Yuan Dynasty, and proclaimed the capital to be at Dadu (Chinese: 大都; Wade–Giles: Ta-tu, lit. "Great Capital", known as Daidu to the Mongols, at modern-day Beijing) the following year. His summer capital was in Shangdu (Chinese: 上都, "Upper Capital", also called Xanadu, near what today is Dolonnur). To unify China,[59] Kublai began a massive offensive against the remnants of the Southern Song Dynasty in the 11th year of Zhiyuan (1274), and finally destroyed the Song Dynasty in the 16th year of Zhiyuan (1279), unifying the country at last.

The Chinese opera flourished during the Mongol rule in China.

Most of the Yuan domains were administered as provinces, also translated as the "branch Secretariat", during his reign, each with a governor and vice-governor.[60] This included China proper, Manchuria, Mongolia and a special Zhendong branch Secretariat that would extend into the Korean Peninsula.[61][62] The Central Region (Chinese: 腹裏) was separate from the rest, consisted of much of present-day North China, was considered the most important region of the dynasty and was directly governed by the Zhongshusheng (Chinese: 中書省, "Department of Central Governing") at Dadu. Tibet was governed by another top-level administrative department called the Xuanzheng Yuan (Chinese: 宣政院).

Kublai promoted economic growth with the rebuilding of the Grand Canal, repaired public buildings, and extended highways. However, his domestic policy included some aspects of the old Mongol living traditions, and as his reign continued, these traditions would clash increasingly frequently with traditional Chinese economic and social culture. Kublai decreed that partner merchants of the Mongols should be subject to taxes in 1263 and set up the Office of Market Taxes to supervise them in 1268. After the Mongol conquest of the Song, the merchants expanded their operations to the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. In 1286, maritime trade was put under the Office of Market Taxes. The main source of revenue of the government was the monopoly of salt production.[63]

The Mongol administration had issued paper currencies from 1227 on.[64][65] In August 1260, Kublai created the first unified paper currency called Chao; bills were circulated throughout the Yuan domain with no expiration date. To guard against devaluation, the currency was convertible with silver and gold, and the government accepted tax payments in paper currency. In 1273, he issued a new series of state sponsored bills to finance his conquest of the Song, although eventually a lack of fiscal discipline and inflation turned this move into an economic disaster. It was required to pay only in the form of paper money. To ensure its use in circles, Kublai's government confiscated gold and silver from private citizens and foreign merchants. But traders received government-issued notes in exchange. Kublai Khan is considered to be the first of fiat money makers. The paper bills made collecting taxes and administering the empire much easier and reduced the cost of transporting coins.[66] In 1287, Kublai's minister Sangha created a new currency, Zhiyuan Chao, to deal with a budget shortfall.[67] It was non-convertible and denominated in copper cash. Later Gaykhatu of the Ilkhanate attempted to adopt the system in Persia and the Middle East, which was a complete failure, and shortly afterwards he was assassinated.

Kublai encouraged Asian arts and demonstrated religious tolerance. Despite his anti-Taoist edicts, Kublai respected the Taoist master and appointed Zhang Liushan as the patriarch of the Taoist Xuanjiao order.[68] Under Zhang's advice, Taoist temples were put under the Academy of Scholarly Worthies. The empire was visited by several Europeans, notably Marco Polo in the 1270s who may have seen the summer capital Shangdu.

Relations with Muslims[]

The scheme of "Muslim trebuchet" (Hui-Hui Pao) used to breach the walls of Fancheng and Xiangyang.

Within the court of Kublai Khan served 30 Muslim high officials. Out of the Yuan dynasty's 12 administrative districts, eight had Muslim governors appointed by Kublai Khan.[69] Muslim scientists were welcomed and astronomers contributed to the construction of the observatory in Shaanxi.[70] Kublai Khan patronized Muslim scholars, Muslim astronomers such as Jamal ad-Din, introduced new instruments and concepts that allowed the correction of the Chinese calendar, Muslim cartographers made accurate maps, and Muslim physicians organized hospitals.[71]

Among Kublai Khan's Muslim governors was Sayyid Ajjal Shams al-Din Omar, who became administrator of Yunnan, he was a well learned man in the Confucian and Taoist traditions. He is also believed to have propagated Islam in China. Another such administrators was Nasr al-Din (Yunnan).

Kublai Khan brought siege engineers, Ismail and Al al-Din to China, together they invented the "Muslim trebuchet" (Hui-Hui Pao), which was utilized by Kublai Khan during the Battle of Xiangyang.[72]

Warfare and foreign relations[]

A Yuan Dynasty hand cannon

Despite that Kublai restricted the functions of the kheshig, he created a new imperial bodyguard, at first entirely Chinese in composition but later strengthened with Kipchak, Alan (Asud), and Russian units.[73][74][75] Once his own kheshig was organized in 1263, Kublai put three of the original kheshig's four shifts under the charges the descendants of Genghis Khan's four assistants, Borokhula, Boorchu and Muqali. Kublai began the practice of having the four great aristocrats in his kheshig sign all jarliqs (decree), a practice that spread to all other Mongol khanates.[76] Mongol and Chinese units were organized using the same decimal organization that Genghis Khan used. The Mongols eagerly adopted new artillery and technologies. Kublai and his generals adopted an elaborate, moderate style of military campaigns in South China. Effective assimilation of Chinese naval techniques allowed the Yuan army to quickly conquer the Song.

Kublai's foreign policy was similar to those of his predecessors, whose foreign policy might be considered as imperialistic. He invaded Goryeo (Korea) and made it a tributary vassal state in 1260. After another Mongol intervention in 1273, Goryeo came under even tighter control of the Yuan.[77][78][79][80][81] Goryeo became a Mongol military base and several myriarchy commands were established there. The court of the Goryeo supplied Korean troops and ocean-going naval force for the Mongol campaigns. Despite the opposition of some of his Confucian-trained advisers, Kublai decided to invade Japan, Burma, Vietnam and Java, following the suggestions of some of his Mongol officials. The attempts of subjugation also included peripheral lands such as Sakhalin, where its indigenous people eventually submitted to the Mongols by 1308, after Kublai's death. These costly conquests and the introduction of paper currency caused inflation. From 1273 to 1276, war against the Song Dynasty and Japan made the issue of paper currency expand from 110,000 ding to 1,420,000 ding.[82]

Invasions of Japan[]

The samurai Suenaga facing Mongol arrows and bombs. Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba (蒙古襲来絵詞), circa 1293.

The Mongolian Yuan troops. Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba (蒙古襲来絵詞).

Kublai Khan twice attempted to invade Japan. It is believed that both attempts were thwarted by bad weather or a flaw in the design of ships that were based on river boats without keels, and his fleets were destroyed. The first attempt took place in 1274, with a fleet of 900 ships. After the first Mongol attack on Japan, Japanese pirates known as Wokou raided Korea, but Mongol-Korean forces pushed them back, and the Wokou pirates decreased their activity due to the increased military preparedness of the Goryeo and the Kamakura. In 1293 the Yuan navy captured 100 Japanese people from Okinawa.[83]

The second invasion occurred in 1281 when Mongols sent two separate forces; 900 ships containing 40,000 Korean, Chinese, and Mongol troops were sent from Masan, while a force of 100,000 sailed from southern China in 3,500 ships, each close to 240 feet (73 m) long. The fleet was hastily assembled and ill-equipped to cope with maritime conditions. In November, they sailed into the treacherous waters that separated Korea and Japan by 110 miles. The Mongols easily took over Tsushima Island about halfway across the strait and then Ika Island closer to Kyushu. The Korean fleet reached Hakata Bay on June 23, 1281 and landed its troops and animals, but the ships from China were nowhere to be seen.

The samurai warriors, following their custom, rode out against the Mongol forces for individual combat but the Mongols held their formation. The Mongols fought as a united force, not as individuals, and bombarded the samurai with exploding missiles and showered them with arrows. Eventually, the remaining Japanese withdrew from the coastal zone inland to a fortress. The Mongol forces did not chase the fleeing Japanese into an area about which they lacked reliable intelligence.

Marine archaeologist Kenzo Hayashida led the investigation that discovered the wreckage of the second invasion fleet off the western coast of Takashima. His team's findings strongly indicate that Kublai rushed to invade Japan and attempted to construct his enormous fleet in one year, a task that should have taken up to five years. This forced the Chinese to use any available ships, including river boats. Most importantly, the Chinese, under Kublai's control, built many ships quickly in order to contribute to the fleets in both of the invasions. Hayashida theorizes that, had Kublai used standard, well-constructed ocean-going ships with curved keels to prevent capsizing, his navy might have survived the journey to and from Japan and might have conquered it as intended. In October 2011, a wreck, possibly one of Kublai's invasion craft, was found off the coast of Nagasaki.[84] David Nicolle wrote in The Mongol Warlords, "Huge losses had also been suffered in terms of casualties and sheer expense, while the myth of Mongol invincibility had been shattered throughout eastern Asia." He also wrote that Kublai was determined to mount a third invasion, despite the horrendous cost to the economy and to his and Mongol prestige of the first two defeats, and only his death and the unanimous agreement of his advisers not to invade prevented a third attempt.[85]

Invasions of Vietnam[]

Kublai Khan also invaded Đại Việt (Vietnam) three times. The first incursion was in 1257, but the Trần Dynasty was able to repel the invasion and ultimately re-established the peace treaty among Yuan Mongol and Đại Việt in the 12th lunar month of 1257. When Kublai became the Great Khan in 1260, the Vietnamese Trần Dynasty sent tribute every three years and received a darughachi.[86][87] However, their kings soon declined to attend the Mongol court in person after the Great Khan sent his envoys ordering the Trần king to open his land to allow the Yuan army to pass through in order to invade the kingdom of Champa. The Đại Việt court refused to open the path to the Mongol (Yuan) army. Kublai Khan sent another envoy to the Đại Việt for Trần king to surrender his land and his kingship. The Trần king assembled all his citizens allowing all to vote on whether to surrender to the Yuan, or stand and fight for their homeland. The vote was a unanimous decision to stand and fight the invaders.

The second Mongol invasion of Đại Việt began in the 12th lunar month of 1284 when the Mongols under the command of Toghan, the prince of Kublai Khan, crossed the border and quickly occupied Thăng Long (now Hanoi) in January 1285 after the victorious battle of Omar in Vạn Kiếp (north east of Hanoi). At the same time Sogetu, second in command of the Yuan's army, from Champa moved northward and rapidly marched to Nghe An in the north central region of Vietnam where the army of the Trần Dynasty under general Trần Kien was defeated and surrendered to him. However, the Trần king and the commander-in-chief Trần Hưng Đạo changed their tactics from defence to attack and struck against the Mongols. In April, General Trần Quang Khải defeated Sogetu in Chuong Duong and the Trần king won a battle in Tây Kết where Sogetu died. Soon after, general Trần Nhật Duật also won a battle in Hàm Tử (now Hưng Yên) and Toghan was defeated by General Trần Hưng Đạo thus Kublai failed in his first attempt to invade Đại Việt. Toghan hid himself inside a bronze pipe to avoid being killed by the Đại Việt archers; this act brought humiliation upon the Mongol Empire and Toghan himself.

After his first failure, Kublai wanted to install Nhân Tông's brother Trần Ích Tắc – who had defected to the Mongols – as king of Annam, but hardship in the Yuan's supply base in Hunan, and Kaidu's invasion forced Kublai to abandon his plans. In 1285 the Brigung sect rebelled, attacking monasteries of Paghspa's sect in Tibet. The Chagatayid Khan, Duwa, helped the rebels, laying siege to Kara-Kocho and defeating Kublai's garrisons in the Tarim basin.[88] Kaidu destroyed an army at Beshbalik and occupied the city the following year. Many Uyghurs abandoned Kashgar for safer bases back in the eastern Yuan. After Kublai's grandson Buqa-Temür crushed the resistance of the Brigung sect, killing 10,000 Tibetans in 1291, Tibet was fully pacified.

The third Mongol invasion began in 1287. It was better organized than the previous effort; a large fleet and plentiful stocks of food were used. The Mongols, under the command of Toghan, moved to Vạn Kiếp from the north west and met the infantry and cavalry of Kublai's Kipchak commander Omar (coming by another way along the Red River) and quickly won the battle. The naval fleet rapidly attained victory in Vân Đồn near Ha Long Bay. However, the Đại Việt General Trần Khánh Dư managed to intercept and captured the heavy, fully stocked cargo ships, filled with food and supplies for Toghan's army. As a result, the Mongolian army in Thăng Long (modern-day Hanoi) suffered an acute shortage of food. With no news about the supply fleet, Toghan ordered his army to retreat to Vạn Kiếp. The Đại Việt army began their general offensive and recaptured a number of locations occupied by the Mongols. Groups of Đại Việt infantry were ordered to attack the Mongols in Vạn Kiếp. Toghan had to split his army into two and retreated in 1288.[citation needed]

In early April 1288 the naval fleet, led by Omar and escorted by infantry, fled home along the Bạch Đằng river. As bridges and roads were destroyed and attacks were launched by Đại Việt troops, the Mongols reached Bạch Đằng without an infantry escort. Đại Việt's small flotilla engaged in battle and pretended to retreat. The Mongols eagerly pursued the Đại Việt troops only to fall into their pre-arranged battlefield. Thousands of small Đại Việt boats quickly appeared from both banks, launched a fierce attack that broke the Mongol's combat formation. The Mongols, meeting such a sudden and strong attack, in panic tried to withdraw to the sea. The Mongols' boats were halted, and many were damaged and sank. At that time, a number of fire rafts quickly rushed toward the Mongols, who were frightened and jumped down to reach the banks where they were dealt a heavy blow by an army led by the Trần king and Trần Hưng Đạo.

The Mongol naval fleet was totally destroyed and Omar was captured. At the same time, Đại Việt's army continuously attacked and smashed to pieces Toghan's army on its withdrawal through Lạng Sơn. Toghan risked his life to take a shortcut through thick forest in order to flee home. The crown prince was banished to Yangzhou for life by his father, Kublai Khan. Nevertheless, Trần king accepted Kublai Khan's supremancy as the Great Khan in order to avoid more conflicts. In 1292, Temür Khan, Kublai Khan's successor, returned all detained envoys and settled for a tributary relationship with Trần king, which continues to the end of the Yuan Dynasty.[87][89]

Southeast Asia and South Seas[]

Three expeditions against Burma, in 1277, 1283 and 1287, brought the Mongol forces to the Irrawaddy Delta, whereupon they captured Bagan, the capital of the Pagan Kingdom in Burma, and established their government.[90] Kublai had to be content with establishing a formal suzerainty but Burma finally became a tributary state, sending tributes to the Yuan court until the Mongols were expelled from China in the 1360s.[91] The Khmer kingdom of Cambodia and small states of Malaya and South India submitted to Kublai's rule between 1278 and 1294. Mongol interests in these areas were commercial and tributary relationships.

During the last years of his reign, Kublai launched a naval punitive expedition of 20–30,000 men against the Javanese kingdom of Singhasari (1293), but the invading Mongol forces were forced to withdraw by the Majapahit Dynasty after considerable losses of more than 3,000 troops. Nevertheless, by 1294, the year that Kublai died, two Thai kingdoms of Sukhotai and Chiangmai had become vassal states of the Yuan Dynasty.[90]

Europe[]

Kublai gives financial support to the Polo family.

Under Kublai, direct contact between East Asia and the West was established, made possible by the Mongol control of the central Asian trade routes and facilitated by the presence of efficient postal services. In the beginning of the 13th century, large numbers of Europeans and Central Asians – merchants, travelers, and missionaries of different orders – made their way to China. The presence of the Mongol power allowed large numbers of Chinese, intent on warfare or trade, to travel to other parts of the Mongol Empire, all the way to Russia, Persia, and Mesopotamia.[citation needed]

Rabban Bar Sauma, the ambassador of Great Khan Kublai and Ilkhan Arghun, travelled from Dadu in the East, to Rome, Paris and Bordeaux in the West, meeting with the major rulers of the period in 1287–1288

Marco Polo, Niccolo Polo's son, accompanied his father and his uncle Maffeo Polo on their second trip to China starting in 1271. Marco Polo was probably the best-known foreign visitor to China and Mongolia. After reaching China in 1275, he spent the next 17 years (1275–1292) under the administration and patronage of Kublai, including official service in the salt administration and trips through the provinces of Yunnan and Fukien.[citation needed]

The capital city of the Emperor[]

The White Stupa in Dadu (or Khanbalic)

After Kublai Khan was proclaimed Khagan at his residence in Shangdu on May 5, 1260, he began to organize the country. Zhang Wenqian, a central government official and a friend of Guo, was sent by Kublai in 1260 to Daming where unrest had been reported in the local population. Guo accompanied Zhang on his mission. Guo was interested in engineering, was an expert astronomer, a skilled instrument maker and understood that good astronomical observations depended on expertly made instruments. Guo began to construct astronomical instruments, including water clocks for accurate timing and armillary spheres which represented the celestial globe. Turkestani architect Ikhtiyar al-Din (also known as Igder) designed the buildings of the city of Khagan or Khanbalic.[92] Kublai also employed foreign artists to build his new capital; one of them, a Nepalese named Arniko, built the White Stupa which was the largest structure in Khanbalic/Dadu.[93]

Zhang advised Kublai that Guo was a leading expert in hydraulic engineering. Kublai knew the importance of water management for irrigation, transport of grain and flood control, and he asked Guo to look at these aspects in the area between Dadu (now Beijing) and the Yellow River. To provide Dadu with a new supply of water, Guo found the Baifu spring in Mount Shen and had a 30 km (19 mi) channel built to move the water to Dadu. He proposed connecting the water supply across different river basins, built new canals with sluices to control the water level and achieved great success with the improvements which he was able to make. This pleased Kublai and Guo was asked to undertake similar projects in other parts of the country. In 1264 he was asked to go to Gansu province to repair the damage that had been caused to the irrigation systems by the years of war during the Mongol advance through the region. Guo travelled extensively along with his friend Zhang taking notes of the work which needed to be done to unblock damaged parts of the system and to make improvements to its efficiency. He sent his report directly to Kublai Khan.[citation needed]

Nayan's rebellion[]

During the conquest of the Jin, Genghis Khan's younger brothers received large appanages in Manchuria.[94] Their descendants strongly supported Kublai's coronation in 1260, but the younger generation desired more independence. Kublai enforced Ögedei Khan's regulations that the Mongol noblemen could appoint overseers and the Great Khan's special officials, in their appanages, but otherwise respected appanage rights. Kublai's son Manggala established direct control over Singan and Shansi in 1272. In 1274, Kublai appointed Lian Xixian to investigate abuses of power by Mongol appanage holders in Manchuria.[95] The region called Lia-tung was immediately brought under the Khagan's control, in 1284, eliminating autonomy of the Mongol nobles there.[96]

The 19th century romantic view of Kublai's four elephants.

Threatened by the advance of Kublai's bureaucratization, Belgutei's fourth generation descendant, Nayan (not confused with Temüge's descendant Nayan), instigated a revolt in 1287. Nayan tried to join forces with Kublai's competitor Kaidu in Central Asia.[97] Manchuria's native Jurchens and Water Tatars, who had suffered a famine, supported Nayan. Virtually all of the fraternal lines under Hadaan, a descendant of Hachiun, and Shihtur, a grandson of Hasar, joined Nayan's rebellion,[98] and because Nayan was a popular prince, Ebugen, a grandson of Genghis Khan's son Khulgen, and the family of Khuden, a younger brother of Güyük Khan, contributed troops for this rebellion.[99]

The rebellion was crippled by early detection and timid leadership. Kublai sent Bayan to keep Nayan and Kaidu apart by occupying Karakorum, while Kublai led another army against the rebels in Manchuria. Kublai's commander Oz Temür's Mongol force attacked Nayan's 60,000 inexperienced soldiers on June 14, while Chinese and Alan guards under Li Ting protected Kublai. The army of Chungnyeol of Goryeo assisted Kublai in battle. After a hard fight, Nayan's troops withdrew behind their carts and Li Ting began bombardment and attacked Nayan's camp that night. Kublai's force pursued Nayan, who was eventually captured and executed without bloodshed[Clarification needed], a traditional way of executing princes.[99] Meanwhile, the rebel prince Shikqtur invaded the Chinese district of Liaoning but was defeated within a month. Kaidu withdrew westward to avoid a battle. However, Kaidu defeated a major Yuan army in Khangai and briefly occupied Karakorum in 1289. Kaidu had ridden away before Kublai could mobilize a larger army.[100]

Widespread but uncoordinated uprisings of Nayan's supporters continued until 1289; these were ruthlessly repressed. The rebel princes' troops were taken from them and redistributed among the imperial family.[101] Kublai harshly punished the darughachis appointed by the rebels in Mongolia and Manchuria.[102] This rebellion forced Kublai to approve the creation of the Liaoyang Branch Secretariat on December 4, 1287, while rewarding loyal fraternal princes.

Later years[]

In Ilkhanate Persia, Ghazan converted to Islam and recognized Kublai Khan as his suzerain.

Kublai Khan dispatched his grandson Gammala to Burkhan Khaldun in 1291. Because Kublai wanted to ensure that he laid claim to the sacred place (Ikh Khorig), Burkhan Khaldun, where Genghis was buried, Mongolia was strongly protected by the Kublaids. Bayan was in control of Karakorum and was re-establishing control over surrounding areas in 1293, so Kublai's rival Kaidu did not attempt any large-scale military action for the next three years. From 1293 on, Kublai's army cleared Kaidu's forces from the Central Siberian Plateau.[citation needed]

After his wife Chabi died in 1281, Kublai began to withdraw from direct contact with his advisers, and issued instructions through one of his other queens, Nambui. Only two of Kublai's daughters are known by name; he may have had others. Unlike the formidable women of his grandfather's day, Kublai's wives and daughters were an almost invisible presence, possibly because Chinese court etiquette demoted females to inferior status.[citation needed]

Kublai's original choice of successor was his son Zhenjin, who became the head of Zhongshusheng ("Department of Central Governing"), and actively administrated the dynasty according to Confucian fashion. Nomukhan, after he returned from captivity in the Golden Horde, expressed resentment that Zhenjin had been made heir apparent but was banished to the north. An official proposed that Kublai should abdicate in favor of Zhenjin in 1285, a suggestion which angered Kublai, who refused to see Zhenjin. Zhenjin died soon afterwards in 1286, eight years before his father. Kublai regretted this and remained very close to his wife, Bairam (also known as Kokejin).

Kublai became increasingly despondent after the deaths of his favorite wife and his chosen heir Zhenjin. The failure of the military campaigns in Vietnam and Japan also haunted him. Kublai turned to food and drink for comfort, became grossly overweight and suffered gout and diabetes. The emperor overindulged in alcohol and the traditional meat-rich Mongol diet, which may have contributed to his gout. Kublai sank into depression because of the loss of family, his poor health and advancing age. Kublai tried every medical treatment available, from Korean shamans to Vietnamese doctors, and remedies and medicines, but to no avail. At the end of 1293, the emperor refused to participate in the traditional New Years' ceremony. Before his death, Kublai passed the seal of Crown Prince to Zhenjin's son Temür, who would become the next Khagan of the Mongol Empire and the second ruler of the Yuan Dynasty. Seeking an old companion to comfort him in his final illness, the palace staff could choose only Bayan, more than 30 years his junior. Kublai weakened steadily, and on February 18, 1294 he died at the age of 78. Two days later, the funeral cortège took his body to the burial place of the khans in Mongolia.[citation needed]

Poetry[]

Longevity Hill in Beijing where Kublai Khan wrote his poem.

Kublai was well versed in Chinese poetry but most of his works have not survived. Only one Chinese poem written by him is included in the Selection of Yuan Poetry (元诗选). It is titled 'Inspiration recorded while enjoying the ascent to Spring Mountain'. It was translated into Mongolian by the Inner Mongolian scholar B.Buyan in the same style as classical Mongolian poetry and transcribed into Cyrillic by Ya.Ganbaatar. It is said that once in spring Kublai Khan went to worship at a Buddhist temple at the Yiheyuan Garden in western Dadu (Beijing) and on his way back ascended the Wanshou Shan (万寿山 - Longevity Hill, Tumen Nast Uul in Mongolian) where he was filled with inspiration and wrote this poem.[103]

- Inspiration recorded while enjoying the ascent to Spring Mountain (陟玩春山纪兴)

- 时膺韶景陟兰峰 Shí yīng sháo jǐng zhì lán fēng; Season Receive Beautiful Scenery Ascend Orchid Peak;

- 不惮跻攀谒粹容 Bù dàn jī pān yè cuì róng; Not Fear Rise Climb Visit Pure Countenance;

- 花色映霞祥彩混 Huā sè yìng xiá xiáng cǎi hùn; Flower Color Project Red-cloud Auspicious Hue Mingle;

- 垆烟拂雾瑞光重 Lú yān fú wù ruì guāng chóng; Earthy Smoke Brush-off Misty Propitious Light Layer;

- 雨霑琼干岩边竹 Yǔ zhān qióng gàn yán biān zhú; Rain Moisten Jade Trunk Rock Edge Bamboo;

- 风袭琴声岭际松 Fēng xí qín shēng lǐng jì sōng; Wind Beat Zither Sound Mountain-range Interval Cedar;

- 净刹玉毫瞻礼罢 Jìng chà yù háo zhān lǐ bà; Clean Buddhist-temple Jade Hair See Ceremony Finish; ('jade hair' means Urna)

- 回程仙驾驭苍龙 Huí chéng xiān jià yù cāng lóng; Return Journey Immortal Carriage Ride Blue Dragon;

This is translated:

|

|

Family[]

Chabi, Khatun of Kublai and Empress of the Mongol Empire

Kublai first married Tegulen but she died very early. Then he married Chabi Khatun of the Khunggirat, who was his most beloved empress. After Chabi's death in 1281, Kublai married Chabi's young cousin, Nambui, in accordance with Chabi's wish.

Kublai and his wives' children included:

- Dorji was the director of the Secretariat and head of the Bureau of Military Affairs from 1263, but was sickly and died young.

- Zhenjin was the father of Temür Khan, Kublai's successor.

- Manggala was a viceroy in Shaanxi.

- Nomukhan

- Khungjil

- Aychi

- Saqulghachi

- Qughchu

- Toghan led Mongol armies into Burma and Vietnam.

- Khulan-temur

- Tsever

- Khutugh beki married the king Chungnyeol and became the Empress of the Goryeo.[104]

- and a further son and two daughters; names unknown.

Legacy[]

Statue of Kublai Khan in Sükhbaatar Square, Ulan Bator. Together with Ögedei Khan's, and the much larger Genghis Khan's statues, it forms a statue complex dedicated to the Mongol Empire.

Kublai's seizure of power in 1260 pushed the Mongol Empire into a new direction. Despite his controversial election, which accelerated the disunity of the Mongols, Kublai's willingness to formalize the Mongol realm's symbiotic relation with China brought the Mongol Empire to international attention. Kublai and his predecessors' conquests were largely responsible for re-creating a unified, militarily powerful China. The Mongol rule of Tibet, Xinjiang, and Mongolia proper from a capital at modern Beijing were the precedents for the Qing Dynasty's Inner Asian Empire.[105]

Cultural references[]

- Kublai and Shangdu or Xanadu are the subject of various later artworks, including the English Romantic Samuel Taylor Coleridge's poem "Kubla Khan", in which Coleridge makes Xanadu a symbol of mystery and splendour.

- Kublai Khan and Xanadu are both mentioned in the song "Xanadu" by Canadian band Rush.

- The British band Frankie Goes To Hollywood reference Xanadu and Kublai Khan in their 1984 song "Welcome to the Pleasuredome": "In Xanadu did Kubla Khan a pleasure dome erect".

- In the film South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut, the song What Would Brian Boitano Do features a lyric that says "...when Brian Boitano built the pyramids, he beat up Kubla Khan"

- Kublai Khan is a playable leader of the Mongolian empire in Sid Meier's Civilization IV

In fiction[]

- Kublai Khan is depicted in Italo Calvino's novel Invisible Cities, in which Kublai talks with Marco Polo about imaginary cities in his empire .

- Conn Iggulden's 2011 novel Conqueror follows Kublai Khan's rise to power, from the Khanate of Güyük Khan to the surrender of Ariq Böke Khan.

- Daughter of Xanadu (2011) by Dori Jones Yang depicts war through the eyes of Kublai Khan's fictional eldest granddaughter, Emmajin Beki.

- Kublai Khan is depicted that, before becoming a Great Khan, he attempts to sway the protagonists Guo Jing and Yang Guo to his side in The Return of the Condor Heroes.

- Citizen Kane, often rated as the best film ever made, is about a man who tries to gain power to improve his legacy. A newsreel announcing his death calls him "America's Kublai Khan," and his home, which is an important symbol of his material legacy, is called Xanadu.

Notes[]

General note: Dates given here are in the Julian calendar. They are not in the proleptic Gregorian calendar.

- ↑ Rossabi, Morris (1988). Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times. University of California Press. p. 13. ISBN 0-520-06740-1.

- ↑ Rossabi, Morris (1988). Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times. University of California Press. pp. 227–228. ISBN 0-520-06740-1.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 893.

- ↑ Marshall, Robert. Storm from the East: from Genghis Khan to Khubilai Khan. p. 224.

- ↑ Borthwick, Mark (2007). Pacific Century. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-4355-0.

- ↑ Howorth, H. H.. The History of the Mongols. II. p. 288.

- ↑ Man, John (2007). Kublai Khan. Bantam. ISBN 0-553-81718-3.

- ↑ Atwood, C. P.. Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. p. 457.

- ↑ Weatherford, Jack. The Secret History of the Mongol Queens. p. 135.

- ↑ Man, John. Kublai Khan. p. 37.

- ↑ Haw, Stephen G.. Marco Polo's China. p. 33.

- ↑ Franke, Herbert; Twitchett, Denis; Fairbank, John King. The Cambridge History of China: Alien regimes and border states, 907–1368. p. 381.

- ↑ Man, John. Kublai Khan. p. 79.

- ↑ Atwood, C. P.. Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongols. p. 613.

- ↑ Du Yuting; Chen Lufan (1989). "Did Kublai Khan's Conquest of the Dali Kingdom Give Rise to the Mass Migration of the Thai People to the South?" (free). Siam Heritage Trust. p. image. http://www.siamese-heritage.org/jsspdf/1981/JSS_077_1c_DuYutingChenLufan_KublaiKhanConquestAndThaiMigration.pdf. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ↑ Weatherford, Jack. Genghis Khan. p. 186.

- ↑ Gazangjia. Tibetan Religions. p. 115.

- ↑ Sun Kokuan. Yu chi and Southern Taoism during the Yuan period, in China under Mongol rule. pp. 212–253.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 502.

- ↑ Prabodh Chandra Bagchi. India and China. p. 118.

- ↑ Kalidas Nag. Greater India. p. 216.

- ↑ Mah, Adeline Yen. China. p. 129.

- ↑ Man, John. Kublai Khan. p. 102.

- ↑ Atwood, C. P.. Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. p. 458.

- ↑ Whiting, Marvin C. Imperial Chinese Military History: 8000 BC – 1912 AD. p. 394.

- ↑ Man, John. Ibid. p. 109.

- ↑ Weatherford, Jack. Genghis Khan and the making of the modern world. p. 120.

- ↑ Салих Закиров. "Дипломатические отношения Золотой орды с Египтом".

- ↑ al-Din, Rashid. Universal History.

- ↑ Rashid al-Din, ibid

- ↑ Howorth, H. H. History of the Mongols section: "Berke khan"

- ↑ H. H. Howorth History of the Mongols from the 9th to the 19th Century: Part 2. The So-Called Tartars of Russia and Central Asia. Division 1

- ↑ Otsahi Matsuwo Khubilai Kan

- ↑ Christopher P. Atwood - ibid

- ↑ Michael Prawdin Mongol Empire and its legacy, p.302

- ↑ Biran, Michael. Qaidu and the Rise of the Independent Mongol State In Central Asia, p.63

- ↑ J. J. Saunders The History of the Mongol Conquests, p.130-132

- ↑ René Grousset The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia, p.294

- ↑ G. V. Vernadsky; The Mongols and Russia, p.155

- ↑ Q. Pachymeres; Bk 5, ch.4 (Bonn ed. 1,344)

- ↑ Rashid al-Din

- ↑ John Man –Ibid, p.74

- ↑ The history of Yuan Dynasty

- ↑ Sh.Tseyen-Oidov – Ibid, p.64

- ↑ The history of the Yuan Dynasty

- ↑ John Man Kublai Khan, p. 207

- ↑ the History of Yuan Dynasty

- ↑ René Grousset The Empire of the Steppes, p.297

- ↑ Thomas T. Allsen The Princes of the Left Hand: An Introduction to the History of the ulus of Orda in the Thirteenth and Early Fourteenth Centuries, p.21

- ↑ Eurasia Archivum Eurasiae medii aevi, p.21

- ↑ Jack Weatherford Genghis Khan, p.195

- ↑ G. V. Vernadsky The Mongols and Russia, pp. 344–366

- ↑ Henryk Samsonowicz, Maria Bogucka A Republic of Nobles, p.179

- ↑ G. V. Vernadsky A History of Russia: New, Revised Edition

- ↑ Morris Rossabi Khubilai Khan: his life and times, p. 115

- ↑ John Man Kublai Khan, p.231

- ↑ J. R. S. Phillips The medieval expansion of Europe, p.122

- ↑ René Grousset The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia, p.304

- ↑ Rossabi, M. Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times, p76

- ↑ "The Mongols and Tibet - A historical assessment of relations between the Mongol Empire and Tibet"

- ↑ Rossabi, M. Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times, University of California Press, p.247, n62

- ↑ The Branch Secretariats of the Yuan Empire

- ↑ Cecilia Lee-fang Chien Salt and state, p.25

- ↑ ^ Jack Weatherford, ibid p.176

- ↑ A. P. Martinez The use of Mint-output data in Historical research on the Western appanages, p.87-100

- ↑ Jack Weatherford The history of Money, p127

- ↑ Igor de Rachewiltz In the service of the Khan: eminent personalities of the early Mongol-Yüan period, p.562

- ↑ John Lagerwey Religion and Chinese society, p.xxi

- ↑ http://www.muslimheritage.com/uploads/1001_Years_of_Missing_Martial_Arts%20.pdf

- ↑ http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/198504/muslims.in.china-the.history.htm

- ↑ http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=00FMIzzsv4MC&pg=PA176&dq=kublai+khan+muslim&hl=en&sa=X&ei=SI-EUrPcG87G7AblhoHwDA&ved=0CEAQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=kublai%20khan%20muslim&f=false

- ↑ C. P. Atwood Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p.354

- ↑ The New Encyclopædia Britannica, p.111

- ↑ David M. Farquhar The Government of China Under Mongolian Rule: A Reference Guide p.272

- ↑ Otto Harrassowitz Archivum Eurasiae medii aeivi [i.e. aevi]., p.36

- ↑ C. P. Atwood Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p.264

- ↑ C. P. Atwood Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p.403

- ↑ Herbert Franke, Denis Twitchett, John King Fairbank The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, p.473

- ↑ Colin Mackerras China's minorities, p.29

- ↑ George Alexander Ballard The influence of the sea on the political history of Japan, p.21

- ↑ Conrad Schirokauer A brief history of Chinese and Japanese civilizations, p.211

- ↑ C. P. Atwood Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p.434

- ↑ Ж.Ганболд, Т.Мөнхцэцэг, Д.Наран, А.Пунсаг-Монголын Юань улс, хуудас 122

- ↑ "Shipwreck may be part of Kublai Khan's lost fleet". October 25, 2011. http://articles.cnn.com/2011-10-25/asia/world_asia_japan-archaeology-shipwreck_1_fleet-ship-invasion?_s=PM:ASIA.

- ↑ Nicolle, David The Mongol Warlords

- ↑ Matthew Bennett, Peter The Hutchinson Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare, p.332

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 Christopher Pratt Atwood Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol empire, p.579

- ↑ M. Kutlukov, "Mongol Rule in Eastern Turkestan". Article in collection Tataro-Mongols in Asia and Europe. Moscow, 1970

- ↑ René Grousset The Empire of the Steppes, p.290

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 René Grousset The Empire of the Steppes, p.291

- ↑ C. P. Atwood Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p.72

- ↑ Alfred Schinz The magic square, p.291

- ↑ Kesar Lall A Nepalese miscellany, p.32

- ↑ Paul Pelliot Notes on Marco Polo, p.85

- ↑ Anne Elizabeth McLaren Chinese popular culture and Ming chantefables, p.244

- ↑ E. P. J. Mullie De Mongoolse prins Nayan, pp.9–11

- ↑ Igor de Rachewiltz In the service of the Khan: eminent personalities of the early Mongol-Yüan period, p.599

- ↑ René Grousset The Empire of the Steppes, p.293

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Reuven Amitai-Preiss, David Morgan The Mongol empire and its legacy, p.33

- ↑ René Grousset The Empire of the Steppes, p.294

- ↑ Rashid al-Din JT, I/2 in TVOIRA

- ↑ Reuven Amitai-Preiss, David Morgan The Mongol empire and its legacy, p.43

- ↑ Ya.Ganbaatar. Yuan ulsiin uyiin mongolchuudiin hyatadaar bichsen shulgiin songomol (Selection of Chinese poems written by Mongolians during the Yuan Dynasty), Ulan Bator, 2007 p.15

- ↑ Cheong-Soo Suh An encyclopaedia of Korean culture, p.84

- ↑ C. P. Atwood Ibid, p.611

Weatherford, Jack 'Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World' pg.210–211

References[]

- Weatherford, Jack. Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World.

- Man, John (2004). Genghis Khan: Life, Death and Resurrection. London; New York: Bantam Press. ISBN 0-593-05044-4.

- Man, John (2007). Kublai Khan: The Mongol King Who Remade China. London; New York: Bantam Press. ISBN 978-0-553-81718-8.

- Morgan, David (1986). The Mongols. New York: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-17563-6.

- Rossabi, Morris. Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times (University of California Press (May 1, 1990)) ISBN 0-520-06740-1.

- Saunders, J.J. The History of the Mongol Conquests (University of Pennsylvania Press (March 1, 2001)) ISBN 0-8122-1766-7.

- Clements, Jonathan (2010). A Brief History of Khubilai Khan. Philadelphia: Running Press. ISBN 978-0-7624-3987-4.

External links[]

- Inflation under Kublai

- Relics of the Kamikaze (Archaeological Institute of America)

The original article can be found at Kublai Khan and the edit history here.