Template:Infobox food

Military chocolate has been a part of the standard United States military ration since the original Ration D or D ration bar of 1937. Today, military chocolate is issued to troops as part of basic field rations and sundry packs. Chocolate rations served two purposes: as a morale boost, and as a high-energy, pocket-sized emergency ration. Military chocolate rations are often made in special lots to military specifications for weight, size, and endurance. The majority of chocolate issued to military personnel is produced by the Hershey Company.

When provided as a morale boost or care package, military chocolate is often no different from normal store-bought bars in taste and composition. However, they are frequently packaged or molded differently. The World War II K ration issued in temperate climates sometimes included a bar of Hershey's commercial-formula sweet chocolate. But instead of being the typical flat thin bar, the K ration chocolate was a thick rectangular bar that was square at each end (in tropical regions, the K ration used Hershey's Tropical Bar formula).

When provided as an emergency field ration, military chocolate was very different from normal bars. Since its intended use was as an emergency food source, it was formulated so that it would not be a tempting treat that troops might consume before they needed it. Even as attempts to improve the flavor were made, the heat-resistant chocolate bars never received enthusiastic reviews. Emergency ration chocolate bars were made to be high in energy value, easy to carry, and able to withstand high temperatures. Withstanding high temperatures was critical since infantrymen would often be outdoors, sometimes in tropical or desert conditions, with the bars located close to their bodies. These conditions would cause typical chocolate bars to melt within minutes.

Logan Bar or D ration[]

The first emergency chocolate ration bar commissioned by the United States Army was the Ration D, commonly known as the D ration. Army Quartermaster Colonel Paul Logan approached Hershey's Chocolate in April 1937, and met with William Murrie, the company president, and Sam Hinkle, the chief chemist. Milton Hershey was extremely interested in the project when he was informed of the proposal, and the meeting began the first experimental production of the D ration bar.

Colonel Logan had four requirements for the D ration Bar. The bar must:

- Weigh 4 ounces (113.4 g)

- Be high in food energy value

- Be able to withstand high temperatures

- Taste "a little better than a boiled potato" (to keep soldiers from eating their emergency rations in non-emergency situations)

Its ingredients were chocolate, sugar, oat flour, cacao fat, skim milk powder, and artificial flavoring. Chocolate manufacturing equipment was built to move the flowing mixture of liquid chocolate and oat flour into preset molds. However, the temperature-resistant formula of chocolate became a gooey paste that would not flow at any temperature.

Chief chemist Hinkle was forced to develop entirely new production methods to produce the bars. Each four-ounce portion had to be kneaded, weighed, and pressed into a mold by hand. The end result was an extremely hard block of dark brown chocolate that would crumble with some effort and was heat-resistant to 120 °F (49 °C).

The resultant bar was wrapped in aluminum foil. Three bars sealed in a parchment packet made up a daily ration and was intended to furnish the individual combat soldier with the 1,800 calories (7,500 kJ) minimum sustenance recommended each day.

Logan was pleased with the first small batch of samples. In June 1937, the United States Army ordered 90,000 D ration or "Logan Bars" and field tested them at bases in the Philippines, Panama, on the Texas border, and at other bases throughout the United States. Some of the bars even found their way into the supplies for Admiral Byrd's third Antarctic expedition.[1] These field tests were successful, and the Army began making irregular orders for the bars.

With the onset of America's involvement in World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the bars were ordered to be packaged to make them poison gas proof. The 4-ounce (112 g) bars' boxes were covered with an anti-gas coating and were packed 12 to a cardboard carton, which was also coated. These cartons were packed 12 to a wooden crate for a total of 144 bars to a crate.

The D ration was almost universally detested for its bitter taste by U.S. troops, and was often discarded instead of consumed when issued.[2] Troops called the D ration "Hitler's Secret Weapon" for its effect on soldiers' intestinal tracts.[2] It could not be eaten at all by soldiers with poor dentition, and even those with good dental work often found it necessary to first shave slices off the bar with a knife before consuming.[2]

During the war years, the bulk of the Hershey Food Corporation's chocolate production was for the military. Between 1940 and 1945, an estimated 3 billion units of the specially formulated candy bars were distributed to soldiers around the world."[3]

Tropical Bar[]

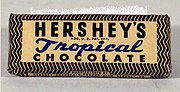

Hershey's Tropical bar from World War 2.

In 1943, the Procurement Division of the Army approached Hershey about producing a confectionery-style chocolate bar with improved flavor that would still withstand extreme heat for issue in the Pacific Theater. After a short period of experimentation, the Hershey company began producing Hershey's Tropical Bar. The bar was designed for issue with field and specialty rations, such as the K ration, and originally came in 1-ounce (28 g) and 2-ounce (56 g) sizes. After 1945, it came in 4-ounce (112 g) D ration sizes as well.

The Tropical Bar (it was called the D ration throughout the war, despite its new appellation) had more of a resemblance to normal chocolate bars in its shape and flavor than the original D ration, which it gradually replaced by 1945. While attempts to sweeten its flavor were somewhat successful, nearly all U.S. soldiers found the Tropical Bar tough to chew and unappetizing; reports from countless memoirs and field reports are almost uniformly negative.[citation needed] Instead, the bar was either discarded or traded to unsuspecting Allied troops or civilians for more appetizing foods or goods. Resistance to accepting the ration soon appeared among the latter groups after the first few trades. In the Burma theater of war (CBI), the D ration or Tropical Bar did make one group of converts: it was known as the "dysentery ration", since the bar was the only ration those ill with dysentery could tolerate.[4]

In 1957, the bar's formula was changed to make it more appetizing. The unpopular oat flour was removed, non-fat milk solids replaced skim milk powder, cocoa powder replaced cacao fat, and artificial vanilla flavoring was added. It was added with the help of sugar. It greatly improved the flavor of the bar, but it was still difficult to chew.

Hershey bars[]

It is estimated that between 1940 and 1945, over 3 billion of the D ration and Tropical Bars were produced and distributed to soldiers throughout the world. In 1939, the Hershey plant was capable of producing 100,000 ration bars a day. By the end of World War II, the entire Hershey plant was producing ration bars at a rate of 24 million a week. For their service throughout World War II, the Hershey Chocolate Company was issued the Army-Navy "E" Award for Excellence for exceeding expectations for quality and quantity in the production of the D ration and the Tropical Bar. Their continued efforts resulted in four stars being added to their pennant signifying the five times they received this distinction. U.S. propaganda used this product distinction during the war as a message "that Allied nations would win the war because of their democratic institutions, but also because of the productivity of the U.S. economy and, especially, its agriculture." In tandem with this state-sponsored rhetoric, radio advertisements for foodstuffs and other consumer goods employed wartime slogans to reinforce military campaigns against Germany and Japan.[5]:770

Postwar to modern day[]

The rhetoric of "war rations aligned food consumption with the war in Europe and Asia but also with the vitality of U.S. agriculture and consumerism. While these campaigns aimed to conserve U.S. food surpluses for the purpose of providing food aid to overseas militaries and civilian populations, they also functioned to jettison certain foodstuffs."[5] Production of the D ration bar was discontinued at the end of World War II. However, Hershey's Tropical Bar remained a standard ration for the United States Armed Forces. The Tropical Bar saw action in Korea and Vietnam as an element of the "Sundries" kit (which also contained toiletries), before being declared obsolete. It briefly returned to use when it was included onboard Apollo 15 in July 1971.[citation needed]

"Congo Bar"/Desert Bar[]

In the late 1980s, the US Army's Natick Labs created a new high-temperature chocolate (dubbed the "Congo Bar" by researchers) that could withstand heat in excess of 140 °F (60 °C).

During Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm, Hershey's Chocolate was the major manufacturer, shipping 144,000 bars to American troops in the southwest Asia theater. While Army spokesmen said the bar's taste was good, troop reactions were mixed and the bar was not put into full production.

Since the war ended before Hershey's supplies of the experimental bar were shipped, the remainder of the production run was packaged in a "desert camo" wrapper and was dubbed the Desert Bar. It proved a brief novelty but Hershey declined to make more after supplies ran out.

See also[]

- Index of military food articles

- Soldier Fuel (formerly HOOAH! bar)

- Goldenberg's Peanut Chews

- Energy bar

References[]

- ↑ "Ration D Bars – Hershey Community Archives" (in en-US). https://hersheyarchives.org/encyclopedia/ration-d-bars/.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Henry, Mark R. and Chappell, Mike, The US Army in World War II (1): The Pacific, Osprey Publishing (2000), ISBN 1-85532-995-6, pp. 20–21

- ↑ Kruper, Jackie. "A Sweet Prison Camp". pp. 58–60.

- ↑ Webster, Donovan, The Burma Road: The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theater in World War II, Harper-Collins (2004), ISBN 0-06-074638-6, p. 181

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Carruth, Allison (2009). "War Rations and the Food Politics of Late Modernism". pp. 767–795. Digital object identifier:10.1353/mod.0.0139.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Category:United States military chocolate. |

- Picture of a Hershey military chocolate bar

- The Army Quartermaster Corps Museum homepage

- Hershey Archives—Ration D Bars

- Hershey Archives—Hershey's Tropical Chocolate Bar

- Price of Freedom: Americans at War—Smithsonian Institution exhibit featuring the Hershey's Tropical Bar

- 69th Tank Battalion—Vietnam war veteran speaks critically about the Hershey's Tropical Bar

The original article can be found at Military chocolate (United States) and the edit history here.