Template:Use dmy dates

| A6M "Zero" | |

|---|---|

| Mitsubishi A6M3 Zero Model 22 (NX712Z), recovered from New Guinea in 1991 and used in the film Pearl Harbor | |

| Role | Fighter |

| Manufacturer | Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd |

| First flight | 1 April 1939 |

| Introduction | 1 July 1940 |

| Retired | 1945 (Japan) |

| Primary users | Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service Chinese Nationalist Air Force |

| Produced | 1940–1945 |

| Number built | 10,939 |

| Variants | Nakajima A6M2-N |

Template:Japanese text

The Mitsubishi A6M Zero was a long-range fighter aircraft, manufactured by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, and operated by the Imperial Japanese Navy from 1940 to 1945. The A6M was designated as the Mitsubishi Navy Type 0 Carrier Fighter (零式艦上戦闘機 rei-shiki-kanjō-sentōki), and also designated as the Mitsubishi A6M Rei-sen and Mitsubishi Navy 12-shi Carrier Fighter. The A6M was usually referred to by its pilots as the "Zero-sen", zero being the last digit of the Imperial year 2600 (1940) when it entered service with the Imperial Navy. The official Allied reporting name was "Zeke", although the use of the name "Zero" was later commonly adopted by the Allies as well.

When it was introduced early in World War II, the Zero was considered the most capable carrier-based fighter in the world, combining excellent maneuverability and very long range.[1] In early combat operations, the Zero gained a legendary reputation as a dogfighter, achieving the outstanding kill ratio of 12 to 1,[2] but by mid-1942 a combination of new tactics and the introduction of better equipment enabled the Allied pilots to engage the Zero on more equal terms.[3]

The Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service ("IJNAS") also frequently used the type as a land-based fighter. By 1943, inherent design weaknesses and the failure to develop more powerful aircraft engines meant that the Zero became less effective against newer enemy fighters that possessed greater firepower, armor, and speed, and approached the Zero's maneuverability. Although the Mitsubishi A6M was outdated by 1944, it was never totally supplanted by the newer Japanese aircraft types. During the final years of the War in the Pacific, the Zero was used in kamikaze operations.[4] In the course of the war, more Zeros were built than any other Japanese aircraft.[5]

Design and development

Mitsubishi A6M3 Zero wreck abandoned at Munda Airfield, Central Solomons, 1943

A6M2 Zero photo c. 2004

Carrier A6M2 and A6M3 Zeros from the aircraft carrier Zuikaku preparing for a mission at Rabaul

A6M3 Model 22, flown by Japanese Ace Hiroyoshi Nishizawa over the Solomon Islands, 1943

The Mitsubishi A5M fighter was just entering service in early 1937, when the Imperial Japanese Navy started looking for its eventual replacement. In May, they issued specification 12-Shi for a new carrier-based fighter, sending it to Nakajima and Mitsubishi. Both firms started preliminary design work while they awaited more definitive requirements to be handed over in a few months.

Based on the experiences of the A5M in China, the Japanese Navy sent out updated requirements in October calling for a speed of 370 mph and a climb to 3,000 m (9,840 ft) in 3.5 min. With drop tanks, they wanted an endurance of two hours at normal power, or six to eight hours at economical cruising speed. Armament was to consist of two 20 mm cannons, two 7.7 mm (.303 in) machine guns and two 30 kg (70 lb) or 60 kg (130 lb) bombs. A complete radio set was to be mounted in all aircraft, along with a radio direction finder for long-range navigation. The maneuverability was to be at least equal to that of the A5M, while the wing span had to be less than 12 m (39 ft) to allow for use on aircraft carriers. All this was to be achieved with available engines, a significant design limitation. The Zero's power plant seldom reached 750 kilowatts (about 1,000 hp) in any of its variants.

Nakajima's team considered the new requirements unachievable and pulled out of the competition in January. Mitsubishi's chief designer, Jiro Horikoshi, felt that the requirements could be met, but only if the aircraft could be made as light as possible. Every possible weight-saving measure was incorporated into the design. Most of the aircraft was built of a new top-secret 7075 aluminium alloy developed by Sumitomo Metal Industries in 1936. Called Extra Super Duralumin (ESD), it was lighter and stronger than other alloys (e.g. 24S alloy) used at the time, but was more brittle and prone to corrosion[6] which was countered with an anti-corrosion coating applied after fabrication. No armor was provided for the pilot, engine or other critical points of the aircraft, and self-sealing fuel tanks, which were becoming common at the time, were not used. This made the Zero lighter, more maneuverable, and the longest range single engine fighter of WWII; which made it capable of searching out an enemy hundreds of miles away, bringing them to battle, then returning hundreds of miles back to its base or aircraft carrier. However, that trade in weight and construction also made it prone to catching fire and exploding when struck by enemy rounds.[7]

With its low-wing cantilever monoplane layout, retractable, wide-set landing gear and enclosed cockpit, the Zero was one of the most modern aircraft in the world at the time of its introduction. It had a fairly high-lift, low-speed wing with a very low wing loading. This, combined with its light weight, resulted in a very low stalling speed of well below 60 kn (110 km/h; 69 mph). This was the main reason for its phenomenal maneuverability, allowing it to out-turn any Allied fighter of the time. Early models were fitted with servo tabs on the ailerons after pilots complained control forces became too heavy at speeds above 300 kilometres per hour (190 mph). They were discontinued on later models after it was found that the lightened control forces were causing pilots to overstress the wings during vigorous maneuvers.[8]

It has been claimed that the Zero's design showed clear influence from American fighter planes and components exported to Japan in the 1930s, and in particular the Vought V-143 fighter. Chance Vought had sold the prototype for this aircraft and its plans to Japan in 1937. Eugene Wilson, President of Vought, claimed that when shown a captured Zero in 1943, he found that "There on the floor was the Vought V 142 [sic] or just the spitting image of it, Japanese-made," while the "power-plant installation was distinctly Chance Vought, the wheel stowage into the wing roots came from Northrop, and the Japanese designers had even copied the Navy inspection stamp from Pratt & Whitney type parts."[9] While the sale of the V-143 was fully legal,[9][10] Wilson later acknowledged the conflicts of interest that can arise whenever military technology is exported.[9] In fact, there was no significant relationship between the V-143 (which was an unsuccessful design that had been rejected by the U.S. Army Air Corps and several export customers) and the Zero, with only a superficial similarity in layout. Allegations about the Zero being a copy have been mostly discredited.[10][11]

Name

The A6M is universally known as the "Zero" from its Japanese Navy type designation, Type 0 Carrier Fighter (Rei shiki Kanjō sentōki, 零式艦上戦闘機), taken from the last digit of the Imperial year 2600 (1940), when it entered service. In Japan, it was unofficially referred to as both Rei-sen and Zero-sen; Japanese pilots most commonly called it Zero-sen, where sen is the first syllable of sentoki, Japanese for "fighter."[N 1] [12]

In the official designation "A6M" the "A" signified a carrier-based fighter, "6" meant it was sixth such model built for the Imperial Navy, and "M" indicated the manufacturer, Mitsubishi.

The official Allied code name was "Zeke", in keeping with the practice of giving male names to Japanese fighters, female names to bombers, bird names to gliders, and tree names to trainers. "Zeke" was part of the first batch of "hillbilly" code names assigned by Captain Frank T. McCoy of Tennessee, who wanted quick, distinctive, easy to remember names. When in 1942 the Allied code for Japanese aircraft was introduced, he logically chose "Zeke" for the "Zero." Later, two variants of the fighter received their own code names: the Nakajima A6M2-N (floatplane version of the Zero) was called "Rufe" and the A6M3-32 variant was initially called "Hap". After objections from General "Hap" Arnold, commander of the USAAF, the name was changed to "Hamp". When captured examples were examined in New Guinea, it was realized it was a variant of the Zero and finally renamed "Zeke 32."

Operational history

Mitsubishi A6M2 "Zero" Model 21 takes off from the aircraft carrier Akagi, to attack Pearl Harbor.

Cockpit (starboard console) of a damaged A6M2 which crashed during the raid on Pearl Harbor into Building 52 at Fort Kamehameha, Oahu, during the 7 December 1941 raid on Pearl Harbor. The pilot, who was killed, was NAP1/c Takeshi Hirano; aircraft's tail code was "AI-154".

The Akutan Zero is inspected by US military personnel on Akutan Island on 11 July 1942.

The first Zeros (pre-series A6M2) went into operation in July 1940.[13] On 13 September 1940, the Zeros scored their first air-to-air victories when 13 A6M2s led by Lieutenant Saburo Shindo attacked 27 Soviet-built Polikarpov I-15s and I-16s of the Chinese Nationalist Air Force, shooting down all the fighters without loss to themselves. By the time they were redeployed a year later, the Zeros had shot down 99 Chinese aircraft[14] (266 according to other sources).[13]

At the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor 420 Zeros were active in the Pacific. The carrier-borne Model 21 was the type encountered by the Americans. Its tremendous range of over 2,600 km (1,600 mi) allowed it to range farther from its carrier than expected, appearing over distant battlefronts and giving Allied commanders the impression that there were several times as many Zeros as actually existed.[15]

The Zero quickly gained a fearsome reputation. Thanks to a combination of excellent maneuverability and firepower, it easily disposed of the motley collection of Allied aircraft sent against it in the Pacific in 1941. It proved a difficult opponent even for the Supermarine Spitfire. Although not as fast as the British fighter, the Mitsubishi fighter could out-turn the Spitfire with ease, could sustain a climb at a very steep angle, and could stay in the air for three times as long.[16]

Soon, however, Allied pilots developed tactics to cope with the Zero. Due to its extreme agility, engaging in a traditional, turning dogfight with a Zero was likely to be fatal. It was better to roar down from above in a high-speed pass, fire a quick burst, then zoom back up to altitude. (A short burst of fire from heavy machine guns or cannon was often enough to bring down the fragile Zero.) Such "boom-and-zoom" tactics were used successfully in the China Burma India Theater (CBI) by the "Flying Tigers" of the American Volunteer Group (AVG) against similarly maneuverable Japanese Army aircraft such as the Nakajima Ki-27 Nate and Ki-43 Oscar. AVG pilots were trained to exploit the advantages of their P-40s, which were very sturdy, heavily armed, generally faster in a dive and level flight at low altitude, with a good rate of roll.[17]

Another important maneuver was Lieutenant Commander John S. "Jimmy" Thach's "Thach Weave", in which two fighters would fly about 60 m (200 ft) apart. If a Zero latched onto the tail of one of the fighters, the two aircraft would turn toward each other. If the Zero followed his original target through the turn, he would come into a position to be fired on by the target's wingman. This tactic was first used to good effect during the Battle of Midway, and later over the Solomon Islands. Many highly experienced Japanese aviators were lost in combat, resulting in a progressive decline in the quality of the opponents faced by Allied pilots, which became a significant factor in Allied successes. Unexpected heavy losses of these irreplaceable pilots at the battles of the Coral Sea and Midway dealt the Japanese carrier air force a blow from which it never fully recovered.[18][19]

In contrast, Allied fighters were designed with ruggedness and pilot protection in mind.[20] The Japanese ace Saburō Sakai described how the resilience of early Grumman aircraft was a factor in preventing the Zero from attaining total domination:

I had full confidence in my ability to destroy the Grumman and decided to finish off the enemy fighter with only my 7.7 mm machine guns. I turned the 20mm cannon switch to the 'off' position, and closed in. For some strange reason, even after I had poured about five or six hundred rounds of ammunition directly into the Grumman, the airplane did not fall, but kept on flying! I thought this very odd—it had never happened before—and closed the distance between the two airplanes until I could almost reach out and touch the Grumman. To my surprise, the Grumman's rudder and tail were torn to shreds, looking like an old torn piece of rag. With his plane in such condition, no wonder the pilot was unable to continue fighting! A Zero which had taken that many bullets would have been a ball of fire by now.[21]

When the powerful Lockheed P-38 Lightning, Grumman F6F Hellcat and Vought F4U Corsair appeared in the Pacific theater, the A6M, with its low-powered engine, was hard-pressed to remain competitive. In combat with an F6F or F4U, the only positive thing that could be said of the Zero at this stage of the war was that in the hands of a skillful pilot it could maneuver as well as most of its opponents.[15] Nonetheless, in competent hands the Zero could still be deadly.

Due to shortages of high-powered aviation engines and problems with planned successor models, the Zero remained in production until 1945, with over 11,000 of all variants produced.

Allied opinions

Recognition of the Japanese Zero Fighter (1943)

The American military discovered many of the A6M's unique attributes when they recovered a largely intact specimen on Akutan Island in the Aleutians (which was called the Akutan Zero). During an air raid over Dutch Harbor on 4 June 1942, one A6M fighter was hit by ground fire. Losing oil, Flight Petty Officer Tadayoshi Koga attempted an emergency landing on Akutan Island about 20 miles northeast of Dutch Harbor, but his Zero flipped over in soft ground in a sudden crash landing. Koga died instantly of head injuries, but the relatively undamaged fighter was found over a month later by an American salvage team and shipped to Naval Air Station North Island where testing flights of the repaired A6M revealed not only its strengths, but also its deficiencies in design and performance.[20][22]

The experts who evaluated the captured Zero found that the plane weighed about 2,360 Kg (5,200 pounds) fully loaded, about half the weight of the standard United States Navy fighter. It was "built like a fine watch"; the Zero was constructed with flush rivets, and even the guns were flush with the wings. The instrument panel was a "marvel of simplicity ... with no superfluities to distract [the pilot]." What most impressed the experts was that the Zero's fuselage and wings were constructed in one piece, unlike the American method that built them separately and joined the two parts together. The Japanese method was much slower, but resulted in a very strong structure and improved close maneuverability.[20]

Captain Eric Brown, the Chief Naval Test Pilot of the Royal Navy, recalled being impressed by the Zero during tests of captured aircraft. "I don’t think I have ever flown a fighter that could match the rate of turn of the Zero. The Zero had ruled the roost totally and was the finest fighter in the world until mid-1943."[2] American test pilots found that the Zero's controls were "very light" at 320 kilometres per hour (200 mph), but stiffened at faster speeds (above 348 km/h, or 216 mph) to safeguard against wing failure.[23] The Zero could not keep up with Allied aircraft in high speed maneuvers, and its low "never exceed speed" (VNE) made it vulnerable in a dive. While stable on the ground despite its light weight, the aircraft was designed purely for the attack role, emphasizing long range, maneuverability, and firepower at the expense of protection of its pilot. Most had neither self-sealing tanks nor armor plating.[20]

Variants

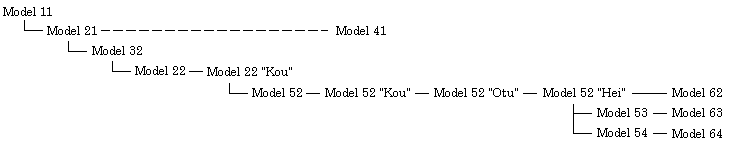

A6M1, Type 0 Prototypes

The first A6M1 prototype was completed in March 1939, powered by the 580 kW (780 hp) Mitsubishi Zuisei 13 engine with a two-blade propeller. It first flew on 1 April, and passed testing in a remarkably short period of time. By September, it had already been accepted for Navy testing as the A6M1 Type 0 Carrier Fighter, with the only notable change being a switch to a three-bladed propeller to cure a vibration problem.

A6M2 Type 0 Model 11

While the Navy was testing the first two prototypes, they suggested that the third be fitted with the 700 kW (940 hp) Nakajima Sakae 12 engine instead. Mitsubishi had its own engine of this class in the form of the Kinsei, so they were somewhat reluctant to use the Sakae. Nevertheless, when the first A6M2 was completed in January 1940, the Sakae's extra power pushed the performance of the Zero well past the original specifications.

The new version was so promising that the Navy had 15 built and shipped to China before they had completed testing. They arrived in Manchuria in July 1940, and first saw combat over Chungking in August. There they proved to be completely untouchable by the Polikarpov I-16s and I-153s that had been such a problem for the A5Ms currently in service. In one encounter, 13 Zeros shot down 27 I-15s and I-16s in under three minutes without loss. After hearing of these reports the Navy immediately ordered the A6M2 into production as the Type 0 Carrier Fighter, Model 11. Reports of the Zero's performance filtered back to the US slowly. There they were dismissed by most military officials, who felt it was impossible for the Japanese to build such an aircraft.

A6M2 Type 0 Model 21

A6M2 "Zero" Model 21 prior to attack on Pearl Harbor, 7 December 1941.

After the delivery of only 65 aircraft by November 1940, a further change was worked into the production lines, which introduced folding wingtips to allow them to fit on aircraft carriers. The resulting Model 21 would become one of the most produced versions early in the war. A feature was the improved range with 520lt wing tank and 320lt drop tank. <Capt Takeo Shibata in Broome's One Day War p45>When the lines switched to updated models, 740 Model 21s had been completed by Mitsubishi, and another 800 by Nakajima. Two other versions of the Model 21 were built in small numbers, the Nakajima-built A6M2-N "Rufe" floatplane (based on the Model 11 with a slightly modified tail), and the A6M2-K two-seat trainer of which a total of 508 were built by Hitachi and the Sasebo Naval Air Arsenal.

A6M3 Type 0 Model 32

A6M3 Model 32.

In late 1941, Nakajima introduced the Sakae 21, which used a two-speed supercharger for better altitude performance, and increased power to 840 kW (1,130 hp). Plans were made to introduce the new engine into the Zero as soon as possible.

The new Sakae was slightly heavier and somewhat longer due to the larger supercharger, which moved the center of gravity too far forward on the existing airframe. To correct for this the engine mountings were cut down by 20 cm (8 in), moving the engine back towards the cockpit. This had the side effect of reducing the size of the main fuel tank (located to the rear of the engine) from 518 L (137 US gal) to 470 L (120 US gal).

The only other major changes were to the wings, which were simplified by removing the Model 21's folding tips. This changed the appearance enough to prompt the US to designate it with a new code name, Hap. This name was short-lived, as a protest from USAAF commander General Henry "Hap" Arnold forced a change to "Hamp". Soon after, it was realized that it was simply a new model of the "Zeke". The wings also included larger ammunition boxes, allowing for 100 rounds for each of the 20 mm cannon.

The wing changes had much greater effects on performance than expected. The smaller size led to better roll, and their lower drag allowed the diving speed to be increased to 670 km/h (420 mph). On the downside, maneuverability was reduced, and range suffered due to both decreased lift and the smaller fuel tank. Pilots complained about both. The shorter range proved a significant limitation during the Solomons campaign of 1942 during which land based Zeros from Truk airbase had to travel significant distances to the combat zones over Guadalcanal.

The first Model 32 deliveries began in April 1942, but it remained on the lines only for a short time, with a run of 343 being built.

A6M3 Type 0 Model 22

In order to correct the deficiencies of the Model 32, a new version with the Model 21's folding wings, new in-wing fuel tanks and attachments for a 330 L (90 US gal) drop tank under each wing were introduced. The internal fuel was increased to 570 L (137 US gal) in this model, regaining all of the range lost in the Model 32 variant.

As the airframe was reverted from the Model 32 and the engine remained the same, this version received the navy designation Model 22, while Mitsubishi called it the A6M3a. The new model started production in December 1942, and 560 were eventually produced. This company constructed some examples for evaluation, armed with 30 mm Type 5 Cannon, under denomination of A6M3b (model 22b).

A few late-production A6M3 Model 22s had a wing similar to the later shortened, rounded tip wing fitted to the A6M5 Model 52. These were probably a transition model, at least one was photographed at Rabaul-East in Mid-1943.

A6M4 Type 0 Model 41

The A6M4 designation was applied to two A6M2s fitted with an experimental turbo-supercharged Sakae engine designed for high-altitude use. The design, modification and testing of these two prototypes was the responsibility of the First Naval Air Technical Arsenal (第一海軍航空廠) at Yokosuka and took place in 1943. Lack of suitable alloys for use in the manufacture of the turbo-supercharger and its related ducting caused numerous ruptures of the ducting resulting in fires and poor performance. Consequently, further development of the A6M4 was cancelled. The program still provided useful data for future aircraft designs and, consequently, the manufacture of the more conventional A6M5, already under development by Mitsubishi Jukogyo K.K., was accelerated.[24]

A6M5 Type 0 Model 52

Mitsubishi A6M "Rei Sen" (Zeke) captured in flying condition and test flown by U.S. airmen

Mitsubishi A6M5 Model 52s abandoned by the Japanese at the end of the war (Atsugi Naval air base) and captured by US forces

Cockpit of an A6M5 Zero Imperial War Museum

Considered the most effective variant,[25] the Model 52 was developed to face the powerful American F6F Hellcat and F4U Corsair, superior mostly for engine power and armament.[13] The variant was a modest update of the A6M3 Model 22, with shorter, non-folding wing tips and thicker wing skinning to permit faster diving speeds, plus an improved exhaust system. The latter used four ejector exhaust stacks, providing an increment of thrust, projecting along each side of the forward fuselage. The new exhaust system required modified "notched" cowl flaps and small rectangular plates which were riveted to the fuselage, just aft of the exhausts. Two smaller exhaust stacks exited via small cowling flaps immediately forward of and just below each of the wing leading edges. The improved roll-rate of the clipped-wing A6M3 was now built in.

Sub-variants included:

- "A6M5a Model 52a «Kou»," featuring Type 99-II cannon with belt feed of the Mk 4 instead of drum feed Mk 3 (100 rpg), permitting a bigger ammunition supply (125 rpg)

- "A6M5b Model 52b «Otsu»," with an armor glass windscreen, a fuel tank fire extinguisher and the 7.7 mm (.303 in) Type 97 gun (750 m/s muzzle velocity and 600 m/1,970 ft range) in the left forward fuselage was replaced by a 13.2 mm/.51 in Type 3 Browning-derived gun (790 m/s muzzle velocity and 900 m/2,950 ft range) with 240 rounds. The larger weapon required an enlarged cowling opening, creating a distinctive asymmetric appearance to the top of the cowling.

- "A6M5c Model 52c «Hei»" with thicker armored glass in the cabin's windshield (5.5 cm/2.2 in) and armor plate behind the pilot's seat. The wing skinning was further thickened in localized areas to allow for a further increase in dive speed. This version also had a modified armament fit of three 13.2 mm (.51 in) Type 3 machine guns (one in the forward fuselage, and one in each wing with a rate of fire of 800 rpm), twin 20 mm Type 99-II guns and an additional fuel tank with a capacity of 367 L (97 US gal), often replaced by a 250 kg bomb.

The A6M5 had a maximum speed of 540 km/h (340 mph) and reached a height of 8,000 m (26,250 ft) in nine minutes, 57 seconds. Other variants were the night fighter A6M5d-S (modified for night combat, armed with one 20 mm Type 99 cannon, inclined back to the pilot's cockpit) and A6M5-K "Zero-Reisen"(model l22) tandem trainer version, also manufactured by Mitsubishi.

A6M6c Type 0 Model 53c

This was similar to the A6M5c, but with self-sealing wing tanks and a Nakajima Sakae 31a engine featuring water-methanol engine boost.

A6M7 Type 0 Model 62

Similar to the A6M6 but intended for attack or Kamikaze role.

A6M8 Type 0 Model 64

Similar to the A6M6 but with the Sakae (now out of production) replaced by the Mitsubishi Kinsei 62 engine with 1,560 hp (1,164 kW), 60% more powerful than the engine of the A6M2.[13] This resulted in an extensively modified cowling and nose for the aircraft. The carburetor intake was much larger, a long duct like that on the Nakajima B6N Tenzan was added, and a large spinner—like that on the Yokosuka D4Y Suisei with the Kinsei 62—was mounted. The larger cowling meant deletion of the fuselage mounted machine gun, but armament was otherwise unchanged from the Model 52 Hei (2 x 20 mm cannon; 2 x 13 mm/.51 in MG). In addition, the Model 64 was modified to carry two 150 L (40 US gal) drop tanks on either wing in order to permit the mounting of a 250 kg (550 lb) bomb on the underside of the fuselage. Two prototypes were completed in April 1945 but the chaotic situation of Japanese industry and the end of the war obstructed the start of the ambitious program of production for 6,300 machines, none being completed.[13][26]

Operators

Post-war

Survivors

A6M2 Model 21 on display at the Pacific Aviation Museum, Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. This aircraft was made airworthy in the early 1980s before it was grounded in 2002.[27]

A6M5 on display at the National Air and Space Museum

Several Zero fighters survived the war and are on display in Japan (in Aichi, Tokyo's Yasukuni War Museum, Kure's Yamato Museum, Hamamatsu, MCAS Iwakuni, and Shizuoka), China (in Beijing), the United States (at the National Air and Space Museum, National Museum of the United States Air Force, the National Museum of Naval Aviation, the Pacific Aviation Museum, the San Diego Air and Space Museum), and the UK (RAF Duxford) as well as the Auckland War Memorial Museum in New Zealand. A restored A6M2-21 (V-173 retrieved as a wreck after the war, and later found to have been flown by Saburō Sakai at Lae) is on display at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. The Museum Dirgantara Mandala in Yogyakarta, Indonesia also has an A6M in its collection.

Another aircraft recovered by the Australian War Memorial Museum in the early 1970s now belongs to Fantasy of Flight in Polk City, Florida. Along with several other Zeros it was found near Rabaul in the South Pacific. The markings suggest that it was in service after June 1943 and further investigation suggests that it has cockpit features conducive to the Nakashima built model 52b. If this is correct, it is most likely one of the 123 aircraft lost by the Japanese during the assault of Rabaul. The aircraft was shipped in pieces to the attraction and it was eventually made up for display as a crashed aircraft. Much of the aircraft is usable for patterns and some of its parts can be restored to one day make this a basis for a flyable aircraft.[28]

Only three flyable Zero airframes exist; two have had their engines replaced with similar American units; only one, the Planes of Fame Museum's A6M5 example, bearing tail number "61-120" has the original Sakae engine.[29]

Although not a survivor, the "Blayd" Zero is a reconstruction based on templating original Zero components recovered from the South Pacific. In order to be considered a "restoration" and not a reproduction, the builders used a small fraction of parts from original Zero landing gear in the reconstruction.[30][31] The aircraft is now on display at the Fargo Air Museum in Fargo, North Dakota.

The Commemorative Air Force's A6M3 was recovered from Babo Airfield, New Guinea, in 1991. It was partially restored from several A6M3s in Russia, then brought to the United States for restoration. The aircraft was re-registered in 1998 and displayed at the Museum of Flying in Santa Monica, California. It currently uses a Pratt & Whitney R1830 engine.[32]

The rarity of flyable Zeros accounts for the use of single-seat North American T-6 Texans, with heavily modified fuselages and painted in Japanese markings, to stand in for the fighter in the films Tora! Tora! Tora!, The Final Countdown, and many other television and film depictions of the aircraft, such as Baa Baa Black Sheep (renamed Black Sheep Squadron). One Model 52 was used during the production of Pearl Harbor.

Specifications (A6M2 Type 0 Model 21)

Data from The Great Book of Fighters[23]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 9.06 m (29 ft 9 in)

- Wingspan: 12.0 m (39 ft 4 in)

- Height: 3.05 m (10 ft 0 in)

- Wing area: 22.44 m² (241.5 ft²)

- Empty weight: 1,680 kg (3,704 lb)

- Loaded weight: 2,410 kg (5,313 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Nakajima Sakae 12 radial engine, 709 kW (950 hp)

- Aspect ratio: 6.4

Performance

- Never exceed speed: 660 km/h (356 kn, 410 mph)

- Maximum speed: 533 km/h (287 kn, 331 mph) at 4,550 m (14,930 ft)

- Range: 3,105 km (1,675 nmi, 1,929 mi)

- Service ceiling: 10,000 m (33,000 ft)

- Rate of climb: 15.7 m/s (3,100 ft/min)

- Wing loading: 107.4 kg/m² (22.0 lb/ft²)

- Power/mass: 294 W/kg (0.18 hp/lb)

Armament

- Guns:

Divergence of trajectories between 7.7 mm and 20mm ammunition

- 2× 7.7 mm (0.303 in) Type 97 light machine guns in the engine cowling, with 500 rounds per gun.

- 2× 20 mm Type 99-1 cannon in the wings, with 60 rounds per gun.

- Bombs:

- 2× 60 kg (132 lb) bombs or

- 1× fixed 250 kg (551 lb) bomb for kamikaze attacks

See also

- Related development

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Brewster F2A Buffalo

- Curtiss-Wright CW-21

- Grumman F4F Wildcat

- Grumman F6F Hellcat

- IAR 80

- Nakajima Ki-43

- Related lists

- List of fighter aircraft

- List of aircraft of Japan, World War II

- List of military aircraft of Japan

- List of aircraft of World War II

References

Notes

- ↑ Note: In Japanese service carrier fighter units were referred to as Kanjō sentōkiti.

Citations

- ↑ Hawks, Chuck. "The Best Fighter Planes of World War II." chuckhawks.com. Retrieved: 18 January 2007.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Thompson with Smith 2008, p. 231.

- ↑ Mersky, Peter B. (Cmdr. USNR). "Time of the Aces: Marine Pilots in the Solomons, 1942–1944." ibiblio.org. Retrieved: 18 January 2007.

- ↑ Willmott 1980, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Angelucci and Matricardi 1978, p. 138.

- ↑ Yoshida, Hideo."History of wrought aluminum alloys for transportation." Sumitomo Light Metal Technical Reports 2005 (Sumitomo Light Metal Industries, Ltd., Japan), Volume 46, Issue 1, pp. 99–116. Retrieved: 15 April 2011.

- ↑ Tillman 1979, pp. 5, 6, 96.

- ↑ Yoshimura 1996, p. 108.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Fernandez 1983, pp. 107–108.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Angelucci and Bowers 1987, p. 436.

- ↑ Air International October 1973, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Parshall and Tully 2007, p. 79.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Matricardi 2006, p. 88.

- ↑ Glancey 2006, p. 170.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Gunston 1980, p. 162.

- ↑ Spick 1997, p. 165.

- ↑ Rossi, J. R. "Chuck Older's Tale: Hammerhead Stalls and Snap Rolls, Written in the mid-1980s." AFG: American Volunteer Group, The Flying Tigers, 1998. Retrieved: 5 July 2011.

- ↑ Holmes 2011, p. 314.

- ↑ Thruelsen 1976, pp. 173, 174.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Wilcox 1942, p. 86.

- ↑ "Saburo Sakai: 'Zero'." acepilots.com. Retrieved: 13 October 2010.

- ↑ Jablonski, Edward. Airwar. New York: Doubleday & Co., 1979. ISBN 0-385-14279-X.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Green and Swanborough 2001

- ↑ "A6M4." J-Aircraft.com. Retrieved: 13 October 2010.

- ↑ Mikesh 1994, p. 53.

- ↑ Francillon 1970, pp. 374–375.

- ↑ "A6M2 Model 21 Zero Manufacture Number 5356 Tail EII-102." Pacific Wrecks. Retrieved: 12 January 2012.

- ↑ "Mitsubishi Zero." Fantasy of Flight. Retrieved: 4 March 2011.

- ↑ Seaman, Richard. "Aircraft air shows." richard-seaman.com. Retrieved: 13 October 2010.

- ↑ "Blayd Corporation." pacificwrecks.com. Retrieved: 29 January 2007.

- ↑ "Examination of Blayd Zero Artifacts." j-aircraft.com. Retrieved: 29 January 2007.

- ↑ "Mitsubishi AM63 Zero." Commemorative Air Force. Retrieved: 11 April 2012.

Bibliography

- Angelucci, Enzo and Peter M. Bowers. The American Fighter. Sparkford, UK: Haynes Publishing, 1987. ISBN 0-85429-635-2.

- Fernandez, Ronald. Excess Profits: The Rise of United Technologies. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Addison-Wesley, 1983. ISBN 978-0-201-10484-4.

- Ford, Douglas. “Informing Airmen? The U.S. Army Air Forces’ Intelligence on Japanese Fighter Tactics in the Pacific Theatre, 1941–5,” International History Review 34 (Dec. 2012), 725–52.

- Francillon, R.J. Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War. London: Putnam, 1970, ISBN 0-370-00033-1.

- Glancey, Jonathan. Spitfire: The Illustrated Biography. London: Atlantic Books, 2006. ISBN 978-1-84354-528-6.

- Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. The Great Book of Fighters. St. Paul, Minnesota, USA: MBI Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0-7603-1194-3.

- Gunston, Bill. Aircraft of World War 2. London: Octopus Books Limited, 1980. ISBN 0-7064-1287-7.

- Holmes, Tony, ed. Dogfight, The Greatest Air Duels of World War II. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2011. ISBN 978-1-84908-482-6.

- Matricardi, Paolo. Aerei Militari. Caccia e Ricognitori (in Italian). Milan: Mondadori Electa, 2006.

- Mikesh, Robert C. Warbird History: Zero, Combat & Development History of Japan's Legendary Mitsubishi A6M Zero Fighter. St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International, 1994. ISBN 0-87938-915-X.

- Parshall, Jonathan and Anthony Tully. Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway. Washington D.C, USA: Potomac Books Inc., 2007. ISBN 978-1-57488-924-6 (paperback).

- Spick, Mike. Allied Fighter Aces of World War II. London: Greenhill Books, 1997. ISBN 1-85367-282-3.

- Thompson, J. Steve with Peter C. Smith. Air Combat Manoeuvres: The Technique and History of Air Fighting for Flight Simulation. Hersham, Surrey, UK: Ian Allan Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-1-903223-98-7.

- Thruelsen, Richard. The Grumman Story. Praeger Press, 1976. ISBN 0-275-54260-2.

- Tillman, Barrett. Hellcat, The F6F In World War II. Naval Institute Press, 1979. ISBN 1-55750-991-3.

- Wilcox, Richard. "The Zero: The first famed Japanese fighter captured intact reveals its secrets to U.S. Navy aerial experts." Life, 4 November 1942.

- Willmott, H.P. Zero A6M. London: Bison Books, 1980. ISBN 0-89009-322-9.

- Yoshimura, Akira, translated by Retsu Kaiho and Michael Gregson. Zero! Fighter. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Praeger Publishers, 1996. ISBN 0-275-95355-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mitsubishi A6M Zero. |

- Tour A6M5 Zero cockpit

- Mitsubishi A6M Zero Japanese fighter aircraft—design, construction, history

- WW2DB: A6M Zero

- www.j-aircraft.com: Quotes A6M

- THE MITSUBISHI A6M ZERO at Greg Goebel's AIR VECTORS

- Imperial Japanese Navy's Mitsubishi A6M Reisen

- Planes of Fame Museum's Flightworthy A6M5 Zero No. "61-120"

- War Prize: The Capture of the First Japanese Zero Fighter in 1941

- Video links

- Planes of Fame "61-120" A6M5 Zero Flight Video on YouTube

- 零戦の美しさ Beauty of the Zerosen on YouTube

Template:Mitsubishi aircraft

| |||||

| |||||||||||

Template:Aviation lists