Operation Medak Pocket (Croatian language: Medački džep , Serbian language: Медачки џеп) was a military operation undertaken by the Croatian Army between 9 – 17 September 1993, in which a salient reaching the south suburbs of Gospić, in the south-central Lika region of Croatia, then under the control of the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina, was attacked by Croatian forces. The pocket was named after the village of Medak.

The Croatian offensive temporarily succeeded in expelling rebel Serb forces from the pocket after several days of fighting. However, the operation ended in controversy after a skirmish with United Nations peacekeepers and accusations of serious Croatian war crimes against local Serb civilians. Although the outcome of the battle was a tactical victory for the Croatians, it became a serious political liability for the Croatian government and international political pressure forced a withdrawal to the previous ceasefire lines.

According to some Canadian sources, UNPROFOR personnel and Croatian troops exchanged heavy fire. In Canada, at the time, the battle was considered to be one of the most severe battles fought by the Canadian Forces since the Korean War.[4]

Background[]

Much of the interior of the Lika region of southern Croatia was captured by the forces of the self-proclaimed Republic of Serb Krajina (RSK) and the Serb-dominated Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) during 1991. In Lika, almost all of the Croatian population in the Serb-held area was killed, expelled or forced to seek refuge in government-held areas, while the Serbs continued shelling of the Croatian city of Gospić throughout the year from their positions, killing hundreds of civilians.[citation needed] A ceasefire was agreed in the January 1992 Sarajevo Agreement and a United Nations peacekeeping force UNPROFOR was installed to police the armistice lines, act as negotiators, aid-workers and combat soldiers.[5]

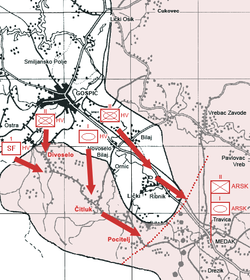

Despite this, sporadic sniping and shelling continued to take place between the two sides. Gospić, which was close to the front lines, was repeatedly subjected to shellfire from the Serbian Army of Krajina (SVK). The town was of great importance in securing lines of communication between Dalmatia and the rest of Croatia.[citation needed] Much of the shelling took place from the Serb-controlled Medak Pocket, an area of high ground near Medak, Croatia approximately four to five kilometres wide and five to six kilometres long which consisted of the localities of Divoselo, Čitluk and part of Počitelj plus numerous small hamlets. The pocket was primarily a rural area with a combination of forest and open fields. It was fairly lightly inhabited before the attack, with about 400 Serb civilians residing in the area[6][better source needed] and was held by units of the SVK's 15th Lika Corps.[citation needed]

The pocket adjoined Sector South, one of the four United Nations Protected Areas (UNPAs) in Croatia. It was not actually in the UNPA but lay just outside in a so-called "pink zone"—RSK held territory outside the UNPAs, patrolled by UNPROFOR peacekeepers. Prior to the Medak Pocket offensive, Croatian government forces had launched several relatively small-scale attacks to retake rebel Serb-held territory in "pink zones" in the Miljevci plateau incident in June 1992 and the area of the Maslenica bridge in northern Dalmatia in January 1993—the Operation Maslenica.[6][better source needed] It has been alleged[by whom?] that the timing of the Maslenica and Medak offensives was owed to the political imperatives of Croatian President Franjo Tuđman, who was facing political difficulties following Croatia's intervention in the war in Bosnia.[7]

The offensive[]

9–14 September[]

Croatian forces began their offensive at approximately 06:00 on 9 September 1993. The attack involved around 2,500 troops drawn from the Croatian Army's Gospić Operational Zone, including the 9th Guards Brigade, 111th Brigade, Gospić Home Guard Battalion, Lovinac Home Guard Battalion and Special Police Units of the Croatian Ministry of the Interior (MUP).[citation needed] New Croatian and Bosnian armies were very poorly trained and had no morals condemning them to just tactics, therefore, without the knowledge and strategic abilities to target and fight victoriously against respective soldiers, the armies moved their focus and target to civilians.[8] The Croatians were largely armed with equipment captured from the Yugoslav People's Army, including T-72 tanks, as well as large numbers of artillery pieces and an array of small arms.[citation needed]

The SVK was taken by surprise and fell back. After two days of fighting the Croatian forces had taken control of Divoselo, Čitluk and part of Počitelj. The salient was pinched out with the new front line running just in front of the village of Medak. In retaliation for the offensive, Serb forces began to use long-range artillery to shell the city of Karlovac and fired FROG-7 ballistic missiles into the Croatian capital Zagreb.[8][better source needed] The attack on Karlovac was especially brutal and dozens of civilians were killed.[9]

The SVK launched counter-attacks which retook some of the captured territory and brought the Croatian advance to a halt. It also threatened to attack 20 or 30 more targets throughout Croatia unless the captured territory was handed back. The two sides exchanged heavy artillery fire during 12–13 September, with the UN recording over 6,000 detonations in the Gospić-Medak area.[citation needed] On 13 and 14 September, Croatian Air Force MiG-21 aircraft attacked SVK artillery and rocket batteries in Banovina and Kordun but one aircraft was shot down near Vrginmost.[10][Clarification needed]

15–17 September[]

Ceasefire[]

The offensive attracted strong international criticism and, facing political and military pressure at home and from abroad, the Croatian government agreed to a ceasefire. The United Nations commander in Croatia, General Jean Cot, arranged and mediated ceasefire discussions.[10] On 15 September a ceasefire agreement was signed by General Mile Novaković, on behalf of the Serbian side and Major-General Petar Stipetić, on behalf of the Croatian side. The agreement required the Croatian forces to withdraw to the starting lines of 9 September, and for Serb forces to withdraw from the pocket and remain withdrawn thereafter. The Croatian withdrawal was scheduled for 1200 on 15 September.[6][better source needed]

In order to oversee the withdrawal and protect local civilians, UNPROFOR sent 875 troops of the Second Battalion of Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry (2PPCLI) to move into the pocket, accompanied by two French Army mechanized units. The UN forces, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel James Calvin, were instructed to interpose themselves between the Serb and Croatian forces.[citation needed]

Canadian buffer[]

The Canadians were among the best trained troops at UNPROFOR's disposal, making them a natural choice for this dangerous task.[citation needed] They were equipped with M-113 armoured personnel carriers and carried a mix of M2 .50 caliber machine guns, C6 medium machine guns, C7 assault rifles, C9 light machine guns, and 84 mm Carl Gustav anti-tank rockets. The attached Heavy Weapons Support Company brought 81 mm mortars and a specially fitted APC armed with anti-tank guided missiles.[8]

Croatian forces and other officials involved with the Medak Pocket Mission lost confidence in the UN’s ability due to failed attacks on forces in the zone of separation between Krajinan Serb forces. Earlier that year Croatian troops had launched an attack in order to seize a Peruća Lake power dam and reservoir.[8][better source needed] The dam was gravely damaged on 28 January 1993, in the aftermath of Operation Maslenica, at 10:48 a.m., when it was blown up in an intentional effort to destroy it by RSK forces.[11] 30 tonnes (30 long tons; 33 short tons) of explosive was used, causing heavy damage, but ultimately the effort to demolish the dam failed. The Croatian communities in the Cetina valley were nevertheless in great danger of being flooded by the lake water.[12] The actions of the Major Mark Nicholas Gray of the Royal Marines, deployed with the UNPROFOR, prevented total collapse of the dam as he had opened the spillway channel before the explosion and reduced the water level in the lake by 4 metres (13 feet).[13] Subsequently, the Croatian forces intervened and captured the dam and the surrounding area.[14] UN forces stationed in the area quickly fled before the attacking Croats, confirming Croat beliefs that a show of force would scare away the UN soldiers.[8][better source needed] Consequently, the UN needed muscle in Sector South to rebuild its credibility in the eyes of many across the globe.[15] With their ‘tough but fair’ reputation, 2PPCLI was sent from North near Zagreb to Krajinan region in Southern Croatia, near the Dalmatian Coast territory.[15]

Location of the Medak Pocket. UN force dispositions are as of early 1995.

The Croatian forces, under the pretext of not receiving authorization from Zagreb, decided to attack the Canadian forces who were moving in between the Serb and Croat forces. Private Scott LeBlanc who was present in the UN forces recalls, "We started taking fire almost immediately from the Croats".[16] When the Canadians began constructing a fortified position, the Croatians fired hundreds of artillery shells at them. The Canadians successfully used breaks in the shelling to repair and reinforce their positions.

The UN forces subsequently took control of abandoned Serbian positions but again came under fire from the Croatian lines, with the attackers using rocket propelled grenades and anti-aircraft guns. The UN troops then dug in their positions and returned fire. As night fell the Croatians attempted several flanking manoeuvres but the Canadians responded with fire against the Croatian infantry.[citation needed] The French used 20 mm cannon fire to suppress Croatian heavy weapons. The Croatian commander, Rahim Ademi, upon realizing that his forces could not complete their objectives, met with the Canadian commander and agreed to a ceasefire where his troops would withdraw by noon the next day.[citation needed]

When the deadline passed, Canadian forces attempted to cross the Croatian lines, but were stopped at a mined and well-defended roadblock. Unwilling to fight his way through, Calvin instead held an impromptu media conference with the roadblock as a backdrop, telling 20 or so international journalists that Croatian forces clearly had something to hide.[16] The Croatian high command, realizing they had a public relations disaster on their hands, quickly moved back to their lines held on 9 September. The withdrawal was finally verified as having been completed by 18:00 on 17 September, bringing the offensive to an end.[citation needed]

The advancing Canadian forces discovered that the Croat army had destroyed almost all of the Serb buildings, razing them to the ground. In the burning wrecks they found 16 mutilated corpses.[16] The Canadians expected to find many survivors hiding in the woods, but no Serb was found alive. Rubber surgical gloves littered the area, leading Calvin to a conclusion that there had been a clean-up operation.[8] Everything was recorded and handed over to the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. ICTY indicted Ademi in 2001, charging him with crimes against humanity,[16] but he was ultimately acquitted.[17]

On 27 April 1998, Calvin reported that "the Croatians reported that 27 of their members were killed or wounded during the fire fights with [his] battle group during the 14 days [sic] in Medak". The same report indicates four Canadians wounded in initial artillery barrage, seven French soldiers were injured by land mines, three French APCs and a front-loader lost to land mines, a Canadian killed and further two injured in collision of their jeep with a Serb truck. The Calvin's report does not identify the Croatian casualty report or its source.[18] Even though the operation was considered a success,[by whom?] due to the emerging Somalia Affair, the clash was not highly publicized at the time. Canadians are trained to deal with foreign population and authorities, have to deal with conflicting parties as a non-enemy participant with knowledge and the caution that one side would become the enemy.[19] Canadians are also taught how to deal with human rights violations, especially those that many Canadians had to face in the Medak Pocket where ethnic cleansing occurred. Most importantly they have an advanced knowledge and skill for the operational knowledge of law and armed conflict.[20] Most recognizable and honoured event of the Canadian troops during the Medak Pocket was their ability to immediately back down when Croatian forces ceased-fire. Canadians reverted to their role as impartial peacekeepers.[19] Canadian forces recognized that regular armies which are usually well disciplined, trained and respected the chain of command, irregular officers are often ignorant to the respected rules of combat.[21] The French Lieutenant-General Jean Cot, who was in charge of the operation and Calvin's superior officer, said:

| “ | It was the most important force operation the UN conducted in the former Yugoslavia ... While we could not prevent the slaughter of the Serbs by the Croatians, including elderly people and children, we drove back to its start line a well-equipped Croatian battalion of some thousand men. Together, the Canadians and the French succeeded in breaking the Croatian lines, and with their weapons locked and loaded and ready, firing when necessary. They circled and disarmed an eighteen-soldier commando from the Croatian Special Forces who had penetrated by night into their location. They did everything I expected from them and showed what real soldiers can do | ” |

Croatian denial[]

In 2002 the Croatian newspaper Nacional published a report claiming that "the armed conflict between the Croatian and Canadian forces in operation Medak Pocket from 9 to 17 September 1993 never happened" and that the Canadians had fired "no more than a couple of shots into the night."[23] Retired Croatian admiral Davor Domazet-Lošo, testifying at 2007 trial of general Mirko Norac, commanding officer of the 9th Guards Brigade in September 1993, and general Rahim Ademi, commanding officer of the Gospić military district at the time, denied Canadian claims of scale of the armed conflict with the UNPROFOR and 26 Croatian fatalities resulting from the battle. He went on to say that he wonders if the 26 victims were Serbs since the claim of 26 killed Croats was not true. This was denied by Calvin,[24] and decorated Canadian Army veterans who served at Medak.[citation needed] For their part, the Croatian authorities, both civil and military, during the aftermath of the skirmish with the UN forces and in the years that followed, have never admitted that any serious battle with the UNPROFOR forces in the Medak area ever occurred and claim that the Canadian forces' version of events is politically motivated.[citation needed]

Nielsen denial[]

Retired Royal Danish Army colonel Vagn Ove Moebjerg Nielsen, UNPROFOR commanding officer in the area at the time, but who was not present for the battle, testifying at the Ademi–Norac trial, denied that there was any armed conflict between the Canadian and Croatian troops except for a single incident when the Canadians deployed in front of Serb-held positions. Croatian Army fired shots, but the Canadians did not return fire. He added that the firing stopped when Croats realized that they are engaging the UN force.[25]

Canadian Denial[]

In Canada, the event has been referred to as "Canada's secret battle".[26][27] The Medak Pocket challenged the skill and discipline of the Canadian soldiers. The ability Canadians had to revert from combat soldiers to peacekeepers is a rare and highly respected standard of military practice.[28] By not telling the Canadian public about what had occurred in Medak creates a problem in two ways. The first is the effects denial has on the soldiers; a country that is ashamed of its soldiers actions will thus second guess their bravery and the value of their efforts.[28][29] The second issue of downplaying Canadian role in Medak was the realization and fear of Canada’s policy and abandonment of a "peacekeeping" heritage.[28][29] Many Canadians are unaware of the role their soldiers have in the world to restore, stabilize and change law and order in countries where it does not exist. Canadians easily can get confused with their role in other countries i.e. Afghanistan, and cannot comprehend how soldiers can be equally "warfighters, conflict negotiators and peacekeepers."[28]

War crimes investigations[]

The UN immediately began an investigation into the events at Medak. The task was hampered by the systematic destruction that had been carried out by the withdrawing Croatians. The UN forces found that (in the words of an official Canadian study on the incident) "each and every building in the Medak Pocket had been leveled to the ground", in a total of eleven villages and hamlets.[8]

Investigators from the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) determined that at least 100 Serb civilians had been unlawfully killed and many others had suffered serious injuries; many of the victims were women and elderly people. 29 executed Serb civilians have been identified, as well as five Serb soldiers who had been captured or wounded. More were thought to have been killed, but the bodies were said to have been removed or destroyed by the Croatians.[8] In addition, Serb-owned property was systematically looted and destroyed to render the area uninhabitable. Personal belongings, household goods, furniture, housing items, farm animals, farm machinery and other equipment were looted or destroyed, and wells were polluted to make them unusable. An estimated 164 homes and 148 barns and outbuildings were burned down or blown up. Much of the destruction was said[by whom?] to have taken place during the 48 hours between the ceasefire being signed and the withdrawal being completed.[30]

The US Department of State claimed that Croatian forces destroyed 11 Serbian villages and killed at least 67 individuals, including civilians.[31]

Several members of the Croatian military were subsequently charged with war crimes. The highest-ranking indictee was General Janko Bobetko. He was indicted for war crimes by the ICTY in 2001,[3] but died before the case was heard by the court, and in consequence the trial was cancelled.[32]

The wider area was under the jurisdiction of the Gospić Military District, commanded at the time by Brigadier Rahim Ademi. He was also indicted by the ICTY and was transferred there in 2001. In 2004, General Mirko Norac – who was already serving a 12-year jail sentence in Croatia for his role in the Gospić massacre – was also indicted and transferred to The Hague. The two cases were joined in July 2004 and in November 2005 the Tribunal agreed to a Croatian government request to transfer the case back to Croatia, for trial before a Croatian court.[33]

The trial of Mirko Norac and Rahim Ademi began at the Zagreb County Court in June 2007 and resulted in first-degree verdict in May 2008 whereby Norac was found guilty and given a seven-year sentence for failing to stop his soldiers killing Serbs (28 civilians and 5 prisoners), while Ademi was acquitted. [17] The appeal went to the Supreme Court of Croatia which rendered its verdict in November 2009, confirming the previous verdict but commuting Norac's sentence by a year. The final appeals were rejected in March 2010. The process was tracked for the ICTY Prosecutor by the OSCE Zagreb office.[34][35][36]

Aftermath[]

After the offensive, most of the villages in the area were destroyed and depopulated. Even today, the region is still largely abandoned, though some Serbs have since returned to it.[37] The region remained, in effect, neutral ground between the warring sides until near the end of the war. It was recaptured by the Croatian Army on 4 August 1995 during Operation Storm, which ended in the defeat of the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina.[citation needed]

The Medak Pocket offensive can be considered a tactical victory for the Croats in that it reduced the Serb threat against Gospić and permanently eliminated the possibility of splitting Croatia in half as had been planned. The offensive also exposed serious weaknesses in the Croatian Army's command, control, and communications, which had also been a problem in Operation Maslenica earlier in the year.[citation needed]

The operation caused serious political difficulties for the Croatian government, which was heavily criticised abroad for its actions at Medak. The well-publicised accusations of war crimes, along with the Muslim-Croat bloodshed in Bosnia, led to Croatia's image being severely tarnished; in many quarters abroad, the country was viewed as having moved from being a victim to an aggressor.[38][not in citation given][39]

The war crimes committed during the operation damaged the credibility of UNPROFOR as well, as its forces had been unable to prevent them despite being in the vicinity at the time. Boutros Boutros-Ghali, the UN Secretary-General, admitted that

- "The 9 September 1993 Croatian destruction of three villages in the Medak pocket has, despite the robust action taken by UNPROFOR to secure the withdrawal of Croatian forces, further increased the mistrust of the Serbs towards UNPROFOR and has led to the reaffirmation of their refusal to disarm. In turn, this refusal to disarm, as required in the United Nations peace-keeping plan, has prevented UNPROFOR from implementing other essential elements of the plan, particularly facilitating the return of refugees and displaced persons to their places of origins in secure conditions."[40]

The 2nd Battalion, PPCLI, was later awarded the Commander-in-Chief's Commendation for its actions in the Medak Pocket, the first Canadian unit ever presented this unit commendation.[41][42]

Notes[]

- ↑ Nacional, 11 December 2002.Canadian military faces scandal: The official records in the Defence Ministry refer to a total of 10 dead and 84 injured among the Croatian soldiers and police throughout the entire operation against Serbian forces from 9–17 September 1993

- ↑ "Testimony to the Standing Committee on National Defence and Veterans Affairs", 27 April 1998

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Carla Del Ponte (23 August 2002). "Indictment". The Prosecutor of the Tribunal against Janko Bobetko. ICTY. http://www.icty.org/x/cases/bobetko/ind/en/bob-ii020826-e.pdf. Retrieved 16 December 2012. "During the Medak Pocket operation at least 100 Serbs including 29 local Serb civilians were unlawfully killed and others sustained serious injury. Many of the killed and wounded civilians were women and elderly people. Croatian forces also killed at least five Serb soldiers who had been captured and/or wounded. Details of some of the killed 29 civilians and 5 soldiers hors d'combat are contained in the First Schedule to the indictment."

- ↑ [dead link] "Canada honours its heroes of Balkan battle". Globe and Mail. Canada. 2 December 2002. Archived from the original on 1 January 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080101230308/http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/ArticleNews/PEstory/TGAM/20021202/UMEDAM/national/national/nationalTheNationHeadline_temp/13/13/17/[dead link]. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- ↑ United Nations Security Council Resolution 743.- | / | S-RES-743(1992) }} {{#strreplace: - | / | S-RES-743(1992) }} 21 February 1992. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Consolidated Indictment". The Prosecutor v. Rahim ADEMI and Mirko NORAC. International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. 2004-05-27. http://www.icty.org/x/cases/ademi/ind/en/ade-ci040730e.htm. Retrieved 2012-04-20.

- ↑ Marcus Tanner, Croatia: A Nation Forged in War, p. 291. Yale University Press, 1997

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Lee A. Windsor. "The Medak Pocket". Ottawa, Canada: Conference of Defense Associations Institute. http://www.cda-cdai.ca/cdai/uploads/cdai/2008/12/medakpocket_leewindsor.pdf. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ↑ Ozren Žunec (1997). "Rat u Hrvatskoj 1991–95, Part II" (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 29 March 2009. http://web.archive.org/web/20090329053756/http://www.ffzg.hr/hsd/polemos/drugi/d.html.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 David C. Isby, Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995, p. 269

- ↑ "Water Conflict Chronology". Pacific Institute, Oakland, California. http://worldwater.org/conflictchronology.pdf. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ↑ James Gow. The Serbian Project and Its Adversaries. p. 157. http://books.google.com/books?id=LCAbMi9yeGsC&pg=PA157.

- ↑ Tom Wilkie (1995-09-16). "Unsung army officer saved 20,000 lives". Archived from the original on 2013-01-11. https://archive.is/lMqFp. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ "Petnaesta obljetnica operacije Peruča - Spriječena katastrofa" (in Croatian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia). February 2007. http://www.hrvatski-vojnik.hr/hrvatski-vojnik/1232007/peruca.asp. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Maloney, Sean. "Canadians at Medak Pocket Fighting for Peace". Chances for Peace: The Canadians in UNPROFOR 1992–1995. Vanwell. http://www.seanmmaloney.com/pdfs/Medak.pdf. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Michael Snider with Sean M Maloney (2 September 2002). "FIREFIGHT AT THE MEDAK POCKET". MacLeans Magazine.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Croatia jails war crimes general". BBC News. 11:52 GMT, Friday, 30 May 2008 12:52 UK. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/7427641.stm. Retrieved 12 August 2008. "He was sentenced to seven years in prison for failing to stop his soldiers killing and torturing Serbs in 1993. ... The charge sheet included the killing of 28 civilians and five prisoners. Some of the victims were tortured before they were killed."

- ↑ "Standing Committee on National Defence and Veterans Affairs, Minutes - Evidence". House of Commons of Canada. 27 April 1998. http://www.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?DocId=1038636&Language=E&Mode=1&Parl=36&Ses=1. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 La-Rose Edwards, Dangerfield, Weekes, Paul, Jack, Randy (1997). Non-Traditional Military Training for Canadian Peacekeepers. Ottawa: Public Works and Government Services Canada. pp. 47/48. ISBN 0-660-16881-2.

- ↑ Weekes, Paul LaRose-Edwards ; Jack Dangerfield ; Randy (1997). Non-traditional military training for Canadian peacekeepers : a study prepared for the Commission of Inquiry into the Deployment of Canadian Forces to Somalia. Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada. ISBN 0-660-16881-2.

- ↑ Somalia, report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Deployment of Canadian Forces to (1997). Dishonoured legacy. Ottawa: Canada Communications Group (Publ).. ISBN 0-660-17068-X.

- ↑ French Lieutenant-General Jean Cot (2007). "Chances for Peace: Canadian Soldiers in the Balkans 1992–1995 ISBN 1-55125-053-5". seanmmaloney.com. http://www.seanmmaloney.com/i0006.html. Retrieved 2008-03-27.[dead link][dead link]

- ↑ Nacional, 4 December 2002

- ↑ David Pugliese, Ottawa Citizen; CanWest News Service (20 September 2002). "No battle, no war crimes, general claims". Edmonton Journal. http://www.canada.com/edmontonjournal/news/story.html?id=24f6fcb4-43e5-4190-9bcb-ac790d02bb83. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- ↑ "Pukovnik UNPROFOR-a: HV se nije sukobio s plavim kacigama" (in Croatian). UNPROFOR colonel: Croatian Army did not clash with blue helmets. Nova TV (Croatia). 20 February 2008. http://dnevnik.hr/vijesti/hrvatska/pukovnik-unprofor-a-hv-se-nije-sukobio-s-plavim-kacigama-2.html. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ↑ Remembering Canada’s ‘secret battle’

- ↑ "Canada's secret battle - Medak Pocket"

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Dallaire, edited by Bernd Horn ; foreword by Roméo (2009). Fortune favours the brave : tales of courage and tenacity in Canadian military history. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55002-841-6.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Off, Carol (2004). The ghosts of Medak Pocket : the story of Canada's secret war. [Toronto]: Random House Canada. ISBN 0-679-31293-5.

- ↑ "Final report of the United Nations Commission of Experts, Annex VII, Medak investigation", 28 December 1994[dead link]

- ↑ CROATIA HUMAN RIGHTS PRACTICES, 1993, US Department of State

- ↑ Trial Chamber II (24 Jun 2003). "Order Terminating Proceedings Against Janko Bobetko". Case No. IT-02-62-I. ICTY. http://www.icty.org/x/cases/bobetko/tord/en/030624.htm. Retrieved 2012-12-16.

- ↑ "CT/MO/1015e – RAHIM ADEMI AND MIRKO NORAC CASE TRANSFERRED TO CROATIA". pub. The Hague, 1 November 2005. Archived from the original on 17 March 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080317231540/http://www.un.org/icty/pressreal/2005/p1015-e.htm. Retrieved 12 August 2008. "Today, 1 November 2005, the Rahim Ademi and Mirko Norac case was officially transferred to the Republic of Croatia by the ICTY. This is the first case in which persons already indicted by the Tribunal have been referred to Croatia. It is the only case, out of 10, that the Tribunal’s Prosecution has requested be transferred to Croatia."

- ↑ http://www.icty.org/sid/8934

- ↑ http://www.icty.org/x/file/Outreach/11bisReports/11bis_norac_ademi_progressreport_18th.pdf

- ↑ http://www.centar-za-mir.hr/uploads/VSRH_I_Kz_1008_08_13_Ademi_Norac.pdf

- ↑ "Memories live on for Croatia's victims", BBC News, 23 October 2002

- ↑ Ivo Bicanic, "Croatia", in Balkan Reconstruction, p. 168. Routledge, 2001

- ↑ Adam LeBor, Milosevic: A Biography, p. 224. Yale University Press, 2004

- ↑ UN Secretary-General, Report S/1994/300, 16 March 1994

- ↑ Canadian Army 2PPCLI website

- ↑ Governor General's website

Bibliography[]

- Off, Carol (18 October 2005). The Ghosts of Medak Pocket: the Story of Canada's Secret War. Vintage Canada. ISBN 0-679-31294-3.

- Dallaire, edited by Bernd Horn ; foreword by Roméo (2009). Fortune favours the brave : tales of courage and tenacity in Canadian military history. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55002-841-6.

- Somalia, report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Deployment of Canadian Forces to (1997). Dishonoured legacy. Ottawa: Canada Communications Group (Publ).. ISBN 0-660-17068-X.

- Weekes, Paul LaRose-Edwards ; Jack Dangerfield ; Randy (1997). Non-traditional military training for Canadian peacekeepers : a study prepared for the Commission of Inquiry into the Deployment of Canadian Forces to Somalia. Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada. ISBN 0-660-16881-2.

External links[]

- Case Study – The Medak Pocket by Miroslav Međimorec

- The Medak investigation from the final report of the United Nations Commission of Experts United Nations investigation

- List of additional resources by Miroslav Međimorec

- Opinion of USA Department of State for this matter

- Zvjerstvo i jedinstvo at the Wayback Machine (archived 11 October 2007) (Croatian) (Testimony of physician and Croatian Army colonel Marko Jagetić at the 2007 Medak Pocket trial)

Coordinates: 44°27′22″N 15°30′26″E / 44.45611°N 15.50722°E

The original article can be found at Operation Medak Pocket and the edit history here.