| Powder River Expedition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Sioux Wars, American Indian Wars | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Sioux Cheyenne Arapaho | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Red Cloud Roman Nose Dull Knife | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,300 soldiers, 179 Indian scouts, 195 civilians | ~2,000 warriors | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~ 30 dead | ~ 100 dead, including women and children | ||||||

| |||||

| |||||

- This event should not be confused with the Big Horn Expedition during the Black Hills War.

The Powder River Expedition, or the Powder River War or Powder River Invasion, of 1865, was a large and far-flung military operation of the United States Army against the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho Indians Montana Territory and what soon was to become Wyoming Territory. Although soldiers destroyed one Arapaho village and established Fort Connor to protect travelers on the Bozeman Trail, the expedition is considered a failure because it failed to defeat the Indians and secure peace in the region.

Background[]

The Sand Creek massacre of Cheyenne in November 1864 intensified Indian reprisals and raids in the Platte River valley. (See Battle of Julesburg) After the raids, the Sioux, Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho congregated in the Powder river country, remote from white settlements and confirmed as Indian territory in the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie. The Indians also perceived that the Bozeman Trail, blazed in 1863 and traversing the heart of the Powder River country, was a threat. Although roads through Indian territory were permitted by the Fort Laramie Treaty, the Sioux, mostly Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho harassed miners and other travelers along the trail in 1864 and 1865. In July 1865, 1,000 Indian warriors in the Battle of Platte Bridge attacked a bridge across the North Platte River near Fort Caspar and succeeded in temporarily shutting down travel on both the Bozeman and the Oregon Trail. After the battle the Indians broke up into small groups and dispersed for their summer buffalo hunt. A weakness of Indian warfare was that they lacked the resources to keep an army in the field for an extended period of time.[1] Major General Grenville M. Dodge ordered the Powder River expedition as a punitive campaign against the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho. It was led by Brigadier General Patrick E. Connor. Dodge ordered Connor to "make vigorous war upon the Indians and punish them so that they will be forced to keep the peace."[2] The Connor expedition was one of the last Indian war campaigns carried out by U.S Volunteer soldiers. One of Connor's guides was Mountain man Jim Bridger. Connor's strategy was for three columns of soldiers to march into the Powder River Country. The "Right Column" was composed of 1,400 Missouri soldiers, mostly mounted, led by Colonel Nelson Cole. It marched from Omaha, Nebraska and was to follow the Loup River in Nebraska westward to the Black Hills and meet up with Connor near the Powder River. The "Center Column" of 600 men was commanded by Samuel Walker of the 16th Kansas Cavalry and was to head north from Fort Laramie and traverse the country west of the Black Hills.[3] The "Left Column" of 675 men was composed of the 6th Michigan Volunteer Cavalry Regiment under Colonel James H. Kidd, recently transferred from the Civil War battlefields of Virginia. This command included 95 Pawnee and 84 Omaha scouts and a wagon train full of supplies with 195 civilian teamsters.[4] General Connor would personally accompany Kidd's column and would move along the Powder River with the goal of establishing a fort near the Bozeman Trail. All three columns were to unite at the new fort. Connor's orders to his commanders were, "You will not receive overtures of peace or submission from Indians, but will attack and kill every male Indian over twelve years of age."[5] Connor's superiors, Generals John Pope and Dodge attempted to countermand this order, but too late as Connor's expedition had already departed and was out of contact.[6] The expedition was troubled from the start. The number of men to be involved in the campaign was reduced from 12,000 to 2,600 because many soldiers were mustered out of the army at the end of the Civil War. The remaining soldiers were "mutinous, dissatisfied, and inefficient." Few of the men and officers had any experience fighting Indians or travel on the Great Plains. Procuring supplies were also a problem.[7]

The soldiers in the Powder River Expedition followed the Powder River from near its mouth to its headwaters.

Cheyenne warrior Roman Nose (misidentified as a Sioux chief in this 1865 stereoscopic view.)

Fort Laramie was General Connor's starting point for the expedition. Plains Indians often visited and camped near the Fort.

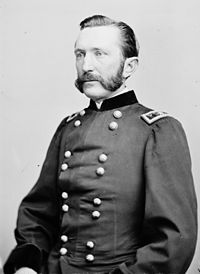

General Patrick E. Connor led the Powder River Expedition.

Mountain man Jim Bridger guided Connor.

The Pawnee Scouts.

Cole and Walker[]

Colonel Cole left Omaha on July 1 with his 1,400 men and 140 wagon-loads of supplies. They followed the Loup River upstream and then went cross country to Bear Butte, near present day Sturgis, South Dakota, arriving there on August 13. Cole, during the 560 mile (900 km) march didn't see a single Indian, but his command suffered from thirst, diminishing supplies, and near mutinies. Colonel Walker and his 600 men left Fort Laramie on August 6 and met up with Cole on August 19 near the Black Hills. He had likewise encountered no Indians and suffered from shortages of water. The two columns marched separately, but remained in contact as they moved westward to the Powder River. By this time the men were barefoot and horses and mules were dying—and they had still not encountered any Indians.[8] In desperate need of supplies, Cole and Walker decided to follow the Powder River north, to search for Connor and his wagon train. On September 1, on Alkali Creek, near Broadus, Montana, they had their first encounter with Indians. About 300 Hunkpapa, Sans Arc, and Miniconjou Lakota Sioux raided the soldiers' horse herd. The soldiers guarding the horses "dropped their guns and run." Six soldiers were killed. The soldiers continued north to the mouth of the Mizpah River east of Miles City, Montana. There, the two commanders decided to turn around and retrace their steps south along the Powder River to look for Connor. They were attacked again on September 5 near Powderville, Montana by 1,000 Cheyenne and Lakotas, the Indians hoping to lure the soldiers into an ambush. The Cheyenne war leader Roman Nose contributed to his legend of invincibility by racing his horse on several occasions in front of the soldiers' guns and escaping untouched.[9] Crazy Horse was among the Lakota attackers. The Cheyenne left the Indian army after this battle, but the Lakota continued to harass Cole and Walker as the soldiers retreated southward up the Powder River. They attacked again on September 8 and 9, but were beaten off. A snowstorm caused further problems for the soldiers most of whom were now on foot, in rags, and reduced to eating raw horse meat. On September 13, Connor's Pawnee scouts found Walker and Cole and led them to the newly established Fort Connor (later Fort Reno) on the Powder River east of Kaycee, Wyoming. Cole and Walker and their soldiers arrived there on September 20. Connor deemed the soldiers unfit for further service and sent them back to Fort Laramie where most of them were mustered out of the army.[10]

Cole reported 12 men killed and two missing. Walker reported one man killed and 4 wounded. Cole claimed that his soldiers had killed 200 Indians. By contrast, Walker said, "I cannot say as we killed one." Indian casualties were likely light. The Cheyenne warrior, George Bent, a participant in the battles, only mentioned one Indian killed and said that the Lakota would have annihilated Cole and Walker had they possessed more good firearms.[11]

Connor and Sawyers[]

General Connor and Colonel Kidd and their 675 soldiers, Indian scouts, and teamsters left Fort Laramie on August 2 to unite with the commands of Cole and Walker. The proceeded northward and established a fort on the upper Powder River which was named Fort Connor. On August 16, Major Frank North and the Pawnee scouts discovered an Indian trail, followed it, attacked a group of 24 Cheyenne warriors, and killed them all. A few days later North had his horse shot from under him by Cheyennes but was rescued by the Pawnee.[12] Connor marched north from Fort Connor and on August 28 his Pawnee scouts found an Arapaho village of about 600 people on the Tongue River near present day Ranchester, Wyoming. The next day Connor attacked the village, whose leader was Black Bear, with 250 cavalry and 80 Pawnee. The people in the village were primarily women, children, and old men. Most of the warriors were absent, engaged in a war with the Crow on the Bighorn River.[13] The surprised Indians fled the village, but regrouped and counterattacked and Connor was dissuaded from pursuing them. The soldiers destroyed the village, captured about 500 horses, and 8 women and 13 children who were subsequently released. Conner claimed to have killed 35 Arapaho warriors, a probably exaggerated estimate, at a cost to himself of 5 dead.[14] (See Battle of the Tongue River) Connor then turned around and returned to Fort Connor, harassed by the Arapaho en route. The Arapaho, who had not been overtly hostile before, now joined the Sioux and Cheyenne.[15] Meanwhile, an expedition commanded by Lieut. Col. James A. Sawyers consisting of train of 80 wagons, engineers, supplies, and escorting soldiers of Companies C and D of the 5th U.S. Volunteer Infantry was en route to meet Connor on the Powder River with the plan to continue on to Montana. Sawyers' group was to construct a new road for the use of emigrants to the Montana gold fields. At Pumpkin Butte, near present day Wright, Wyoming a band of Cheyenne and Sioux killed several men and surrounded the wagon train. After four days of sniping back and forth, Red Cloud, Dull Knife, and George and his brother Charles Bent negotiated with Sawyer a safe passage for the wagon train in exchange for a wagon load of supplies. George Bent, the soldiers reported, was dressed in a U.S. military uniform. The wagon train moved on but, on September 1, Arapaho, infuriated by the destruction of their village on the Tongue River, attacked the wagon train, killing three men and losing two of their own, and holding the wagon train under virtual siege for two weeks when it was finally rescued by Connor's forces.[16] (See Sawyers Fight)

Aftermath[]

Connor finally united all the components of his expedition on September 24 at Fort Connor. However, orders transferring him to Utah were awaiting him when he arrived there. The 16th Kansas Volunteer Cavalry remained to staff Fort Connor and all other troops withdrew to Fort Laramie, most to be mustered out of the army. Although achieving some successes, the expedition failed to defeat decisively or intimidate the Indians. Indian resistance to travelers on the Bozeman Trail became more determined than ever. "There will be no more travel on that road until the government takes care of the Indians," a correspondent wrote.[17] The most important consequence of the expedition was to persuade the United States government that another effort to build and protect a wagon road from Fort Laramie to the gold fields in Montana was desirable. That conviction would lead to a renewed invasion of the Powder River country a year later and Red Cloud's War in which the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho would emerge victorious.[18]

See also[]

References[]

- ↑ McGinnis, Anthony "Strike & Retreat: Intertribal Warfare and the Powder River War, 1865-1868" Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol 30, No. 4 (Autumn 1980), pp. 32-34

- ↑ Hampton, H.D. "The Powder River Expedition 1865" Montana: The Magazine of Western History,Vol.14, No. 4 (Autumn 1964), p. r

- ↑ Hampton, p. 7

- ↑ Hampton, p. 8; Countant, Charles Griffin, "History of Wyoming, Chapter xxxvi, http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~wytttp/history/countant/chapter36.htm, accessed 6 Aug 2012

- ↑ http://rootswebancestry.com/~wyttp/history/countant/chapter34.htm

- ↑ Hampton, pp. 8-9

- ↑ Hampton, p.6

- ↑ Hampton, p. 10

- ↑ Michno, Gregory F. "Battle of Powder River" http://www.forttours.com/pages/powderrivermt.asp, accessed 6 Aug 2012.

- ↑ Hyde, George E. Life of George Bent: Written from his Letters Norman: U of OK press, pp. 240-241

- ↑ Hyde, pp. 240-241

- ↑ Grinnell, George Bird The Fighting Cheyennes Norman: U of OK Press, 1915, pp. 177

- ↑ McDermott, John Dishon (2003). Circle of Fire: The Indian War of 1865. Stackpole Books. pp. 112. ISBN 978-0-8117-0061-0

- ↑ Hampton, p. 13

- ↑ "Powder River (Montana) http://www.enotes.com/topic/Tongue_River_(Montana)?print=1, accessed 9 Aug 2012

- ↑ Grinnell, pp. 208-209;McDermott, p. 124-127

- ↑ Brown, Dee. "The Fetterman Massacre Lincoln: U of NE Press, 1962, p. 15

- ↑ Hampton, p. 14

The original article can be found at Powder River Expedition (1865) and the edit history here.