| Saint John River Campaign | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of French and Indian War | |||||

Robert Monckton British commanders in the Saint John River Campaign. | |||||

| |||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

|

Robert Monckton George Scott Joseph Gorham Moses Hazen Benoni Danks Silvanus Cobb |

Joseph Bernard (Beausoliel) Charles Deschamps de Boishébert et de Raffetot | ||||

| Units involved | |||||

| 40th Regiment of Foot, Gorham's Rangers, Danks' Rangers | Acadia militia, Wabanaki Confederacy (Maliseet and Mi'kmaq) | ||||

| |||||

The St. John River Campaign occurred during the French and Indian War when Colonel Robert Monckton led a force of 1150 British soldiers to destroy the Acadian settlements along the banks of the Saint John River (New Brunswick) until they reached the largest village of Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas (present day Fredericton, New Brunswick) in February 1759.[1] Monckton was accompanied by Captain George Scott as well as New England Rangers led by Joseph Goreham, Captain Benoni Danks, and Moses Hazen.[2] Under the naval command of Silvanus Cobb, the British started at the bottom of the river with raiding Kennebecais and Managoueche (City of St. John), where the British built Fort Frederick. Then they moved up the river and raided Grimross (Gagetown, New Brunswick), Jemseg, and finally they reached Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas. There were about 100 Acadian families on the St. John River, with a large concentration at Ste Anne.[3] Most of whom had taken refuge there from earlier deportation operations, such as the Ile Saint-Jean Campaign.[4] There was also about 1000 Maliseet.[5] According to one historian, the level of Acadian suffering greatly increased in the late summer of 1758. Along with campaigns on Ile Saint-Jean, in the Gult of St. Lawrence, at Cape Sable Island and the Petitcodiac River Campaign, the British targeted the St. John River.[6]

Historical context[]

Boishebert (1753)

The British Conquest of Acadia happened in 1710. Over the next forty-five years the Acadians refused to sign an unconditional oath of allegiance to Britain. During this time period Acadians participated in various militia operations against the British and maintained vital supply lines to the French Fortress of Louisbourg and Fort Beausejour.[7] During the French and Indian War, the British sought to neutralize any military threat Acadians posed and to interrupt the vital supply lines Acadians provided to Louisbourg by deporting Acadians from Acadia.[8]

Acadians had lived in the St. John valley almost continuously since the early seventeenth century.[9] After the Conquest of Acadia (1710), Acadians migrated from peninsula Nova Scotia to the French-occupied Saint John River. These Acadians were seen as the most resistant to British rule in the region.[10] (The Maliseet, from their base at Meductic, conducted effective warfare against New England throughout the colonial wars.) As late as 1748, there were only twelve French-speaking families living on the river.[9] With the migration of returning Acadians after the close of the Seven Years' War in the 1760s to the river valley and other areas of what is now New Brunswick, the region became the center of Acadian life in the maritime region.[9] The first wave of these deportations began in 1755 with the Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755). During the explusion, the St. John River valley became the center of the Acadian and Wabanaki Confederacy resistance to the British military in the region.[11] The leader of the resistance was French militia officer Charles Deschamps de Boishébert et de Raffetot. He was stationed at Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas and from there issued orders for various raids such as the Raid on Lunenburg (1756) and the Battle of Petitcodiac (1755). He was also responsible to locate the Acadian refugees along the St. John River.

After the Siege of Louisbourg (1758), the second wave of the Expulsion of the Acadians began with the Ile Saint-Jean Campaign (campaign against present-day Prince Edward Island), and the removal of Acadians from Ile Royale (Cape Breton, Nova Scotia). As a result, Acadians fled these areas for the villages along the banks of the St. John River, including the largest communities at Grimrose (present day Gagetown, New Brunswick) and Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas.

Fort Frederick[]

St. John River Campaign: The Construction of Fort Frederick (1758)

On September 13, 1758, Monckton and a strong force of regulars and rangers left Halifax and arrived at the mouth of the St. John River a week later. While Fort Menagoueche had been destroyed (1755), when the British arrived, a few militia members fired shots from the site and fled upstream in boats. The armed sloop Providence was wrecked in the Reversing Falls trying to follow.[12] Monckton established a new base of operations by reconstructing Fort Menagoueche, which he renamed Fort Frederick.[13] Establishing Fort Frederick allowed the British to virtually cut off the communications and supplies to the villages on the St. John River.[14] Monckton was accompanied by the New England Rangers, which had three companies that were commanded by Joseph Goreham, Captain Benoni Danks and George Scott.[2] When Monckton and his troops appeared on the St. John River, Boishébert retreated.[4] The Acadians were left unprotected in their settlements at Grimross, Jemseg and Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas. Boishébert directed Acadians to go to Quebec City.

Raid on Grimrose[]

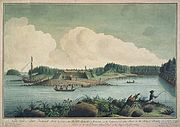

St.John River Campaign: Raid on Grimrose (present day Gagetown, New Brunswick). This is the only known contemporaneous image of the Expulsion of the Acadians.

On October 1 Monckton left Fort Frederick with his boats, regulars and rangers above the Reversing Falls. Two days later, they arrived at the village of Grimrose. The village of 50 families that had migrated there in 1755 were forced to abandon their homes. Monckton’s troops burned every building, tourched the fields, and killed all the livestock.[15]

Raid on Jemseg[]

Two days later, Monckton arrived at the village of Jemseg, New Brunswick and burned it to the ground. Then he returned to Fort Frederick at the mouth of the St. John River.[2]

Raid on Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas[]

St. John River, New Brunswick

Monckton did not continue on to Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas (present day Fredericton, New Brunswick) because of the impending winter. Then, afraid of being trapped by the frozen river, he turned around at Maugerville and went back to Fort Frederick, and afterwards sailed for Halifax with thirty Acadian families as prisoners.[16] Major Robert Morris was put in charge of the fort.[17]

Almost three months later, on February 1759, Monckton sent Captain John McCurdy and his rangers out from Fort Frederick to go to Ste. Anne's Point on snow- shoes.[18] Captain McCurdy died of an accident along the way and was replaced by Lieutenant Moses Hazen. When the Acadians realized the British were going to continue their advance, they retreated to the Maliseet village at Aukpaque (Ecoupag) for protection.

On 18 February 1759, Lieutenant Hazen and about fifteen men arrived at Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas. They pillaged and burned the village of 147 buildings, including two Mass-houses and all of the barns and stables. They burned a large store-house, and with it a large quantity of hay, wheat, peas, oats, etc., killing 212 horses, about 5 head of cattle, a large number of hogs and so forth. They also burned the church (located just west of Old Government House, Fredericton).[19]

Captain George Scott by John Singleton Copley (c.1758), The Brook

As well, the rangers scalped six Acadians and took six prisoners.[19] There is a written record of one of the Acadian survivors Joseph Godin-Bellefontaine. He reported that the rangers restrained him and then massacred his family in front of him. There are other primary sources that support his assertions.[20] (While the French military hired Natives to gather British scalps, the British military hired Rangers to gather Native scalps.[21] The scalping of Acadians in this instance was unique for the Maritimes. New Englanders had been scalping native peoples in the area for generations, but unlike the French on Ile Royale, they had refrained from authorizing the taking of scalps from individuals identified as being of European descent.[22]) On 18 May 1759 a group of soldiers left the confines of Fort Frederick to go fishing. They were attacked by a group of native warriors and fled to the protection of the fort walls. One soldier did not make it and the natives carted him off.[23] Again on 15 June 1759, another party of soldiers was out fishing on the river and was ambushed by a militia of Acadians and natives. During the fight the soldiers fought from the confines of a sloop while others fired cannons from the fort. One of the soldiers was killed and scalped and another was badly wounded. The soldiers pursued the militia but was unable to find it.[23]

The command at Fort Frederick was not convinced the village was totally destroyed and sent at least three more expeditions up river to Ste Anne between July and September 1759. The soldiers captured some Acadians along the way, burned their homes, destroyed their crops and slaughtered their cattle. The September expedition involved more than 90 men. At present-day French Lake on the Oromocto River, they met fierce resistance from the Acadians, and resulted in the death of at least seven rangers.[24]

Consequences[]

Because the British campaign destroyed their supplies, the few surviving Acadians in the area suffered famine. Canada’s Governor Vaudreuil reported 1600 Acadians immigrated to Québec City in 1759. During this same winter, Quebec also suffered a famine and a smallpox epidemic broke out, killing over 300 Acadian refugees.[25] Some returned to St. John only to be imprisoned on Georges Island in Halifax Harbour. In the spring of 1759 twenty-nine of the refugees from the St. John River area went farther up the St. Lawrence to the area around Bécancour, Quebec, where they successfully established a community.[26]

After the fall of Quebec on September 18, 1759, the resistance ended. The Maliseet and Acadians of the St. John River surrendered to the British at Fort Frederick[27] and Fort Cumberland.[28] On 2 January 1760 most of the Acadian men who had come to Fort Frederck were boarded onto ships. The next day, the women and children were put on board, and the ship sailed for Halifax. Within weeks of their arrival in the provincial capital the captured Acadians were bound for France.[29]

In 1761, there were 42 Acadians at St Ann and 10-12 at Grimross.[30] In 1762, Lieutenant Gilfred Studholme, who commanded the garrison at Saint John, was unsuccessful in removing the remaining Acadians from the St. John River in preparation for the arrival of the New England Planters.[31]

References[]

Secondary sources[]

- Campbell, Gary. The Road to Canada: The Grand Communications Route from Saint John to Quebec. Goose Lane Editions and the New Brunswick Military Heritage Project. 2005

- Faragher, John. A Great and Nobel Scheme. Norton. 2005. p. 405.

- Grenier, John. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Oklahoma University Press.pp. 199–200

- Macfarlane, W. G. Fredericton History; Two Centuries of Romance, War, Privation and Struggle, 1981

- Maxwell, L.M.B. An Outline of the History of Central New Brunswick to the Time of Confederation, 1937. (Republish in 1984 by the York-Sunbury Historical Society.)

- Patterson, Stephen E. 1744-1763: Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples. In Phillip Buckner and John Reid (eds.) The Atlantic Region to Conderation: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 1994. pp.125-155

- Plank, Geoffrey. "New England Soldiers in the Saint John River Valley: 1758-1760" in New England and the Maritime provinces: connections and comparisons By Stephen Hornsby, John G. Reid. McGill-Queen's University Press. 2005. pp. 59–73

- Raymond, William O. The River St. John: Its Physical Features, Legends and History from 1604 to 1784. St. John, New Brunswick. 1910. pp. 96–107

- Thériault, Fidèle. Le village acadien de la Pointe-Sainte-Anne (Fredericton),

Primary sources[]

External links[]

- Acadians on the St. John River by Stephen White

- Le Grand Dérangement

- L. M. B. Maxwell - The Jouney to Saint Anne

- Major George Scott and the French and Indian War

- St. John River Campaign - primary sources

Endnotes[]

- ↑ John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Oklahoma University Press.pp. 199-200. Note that John Faragher in the Great and Nobel Scheme indicates that Monckton had a force of 2000 men for this campaign. p. 405.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Oklahoma University Press.pp. 199-200

- ↑ Plank, p. 61

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Maxwell, p. 25.

- ↑ Patterson, p. 126

- ↑ Grenier, 198-200

- ↑ John Grenier, Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia 1710-1760. Oklahoma University Press. 2008

- ↑ Stephen E. Patterson. "Indian-White Relations in Nova Scotia, 1749-61: A Study in Political Interaction." Buckner, P, Campbell, G. and Frank, D. (eds). The Acadiensis Reader Vol 1: Atlantic Canada Before Confederation. 1998. pp.105-106.; Also see Stephen Patterson, Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples, p. 144.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Plank, p. 164

- ↑ Georrery Plank. An Unsettled Conquest. University of Pennsylvania. 2001. p. 100.

- ↑ Plank, p. 150

- ↑ Roger Sarty and Doug Knight. Saint John Fortifications. 2003. p. 29

- ↑ Roger Sarty and Doug Knight. Saint John Fortifications. 2003. p. 31; John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Oklahoma University Press.pp. 199-200; F. Thériault, p. 11

- ↑ Plank, p. 68

- ↑ John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Oklahoma University Press.pp. 199.

- ↑ Campbell, p. 29

- ↑ Maxwell, p. 25

- ↑ [F. Thériault, p. 15.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Oklahoma University Press, p. 202; Also see Plank, p. 61

- ↑ A letter from Fort Frederick which was printed in Parker’s New York Gazette or Weekly Post-Boy on 2 April 1759 provides some additional details of the behavior of the rangers. Also see William O. Raymond. The River St. John: Its Physical Features, Legends and History from 1604 to 1784. St. John, New Brunswick. 1910. pp. 96-107

- ↑ The regiments of both the French and British militaries were not skilled at frontier warfare, while the Natives and rangers were. British officers Cornwallis and Amherst both expressed dismay over the tactics of the rangers and the Mi'kmaq (See Grenier, p.152, Faragher, p. 405).

- ↑ Plank, p. 67

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Plank, p. 66

- ↑ Plank, p. 62, p. 66; Campbell, p. 31 (note that Campbell reports five rangers killed and eight wounded)

- ↑ G. Desilets., pp. 14-15.

- ↑ G. Desilets, p. 15.]

- ↑ John Faragher, p. 412

- ↑ Stephen E. Patterson, "Indian-White Relations in Nova Scotia, 1749-1761: A Study in Political Interaction," Acadiensis 23, no. 1 (Autumn 1993): 23-59.

- ↑ Plank, p. 62

- ↑ Murdoch. History of Nova Scotia. Vol. 2. p. 403

- ↑ Campbell, p. 31

The original article can be found at St. John River Campaign and the edit history here.