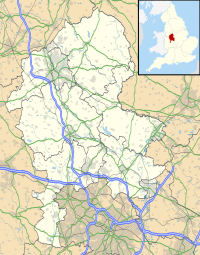

| Stafford Castle | |

|---|---|

| Staffordshire, England | |

Stafford Castle | |

| Coordinates | grid reference SJ902222 |

| Type | Motte and bailey, later Gothic Revival |

Stafford Castle lies two miles to the west of Stafford, just off the A518 Stafford-to-Newport Road, and can be seen from and to the east of the M6 motorway. The stone building is an important early example of a 19th-century Gothic Revival Keep. The structure was built on the foundations of its medieval predecessor and incorporates much of the original stonework.

History[]

Medieval and Early Modern[]

A wooden castle was originally built on the site at some time in the 1070s by the Norman lord Robert de Tosny who had been given a large amount of land in the area by William of Normandy in order to control the still hostile and rebellious native Anglo-Saxon community.[1] Shortly before the castle was built Eadric the Wild had led a failed rebellion which culminated in the defeat of the Saxons at the battle of Stafford in 1069.[1] The first development was built in the classic motte and bailey style, although it incorporated two baileys and a village beyond. The outline of the site's defences can still be seen today. The banks and ditches have been interpreted by an archaeological illustrator whose watercolours feature on a Heritage Trail which encompases much of the ten acre site. The trail takes 45 minutes to walk with short-cuts which are either fifteen minutes (trial-boards 1–5 and straight up the inner bailey gateway) or ten minutes (board 1 and 10 which is straight up the modern drive). Each of the boards has a map, so it is difficult to get lost.

The castle was originally a timber and earth fortification, built on modified glacial deposit. The artificial horizon of the motte or mound is still well defined, as are many of the ditches. The earthworks cover over ten acres, while the site backs onto woodland (sixteen acres), which may once have been cleared for housing livestock. Beyond these earthworks once lay three medieval deer parks.

Ralph de Stafford sealed a contract with a master mason in 1347, ordering a castle to be built on the castle mound. The rectangular stone Keep originally had a tower in each corner, but was later adapted, with a fifth tower being added on in the middle of the North Wall (actually facing west). Some three years later, Ralph, who had been one of the King's leading commanders in the first phases of the Hundred Years' War, was created first Earl of Stafford, a signal honour.

In 1444, Humphrey Stafford was created Duke of Buckingham and the castle reached its heyday. Humphrey's grandson, Henry, had become a ward of the Yorkists following his death at the battle of Northampton in 1460. Henry was initially a supporter of Richard III, but later rebelled in favour of the aborted invasion of Henry Tudor (Henry VII) in 1483. Henry Stafford, second Duke of Buckingham paid with his life, but his son, Edward Stafford, escaped and was later restored to his lands by a grateful Henry VII.

Edward Stafford's royal blood made him a threat to Henry VIII, who had him executed in 1521.[2] The Stafford's Estate, which included the castle and its deer parks, was seized by the Crown. The King's auditors commented on the deer to be had in the parks and though the castle might be a suitable stop-off on one of the King's progresses.

Stafford Castle, along with a small parcel of land, was restored to the Staffords, but they never regained the wealth or status of earlier years. Through lack of maintenance, the Keep fell into disrepair and in 1603, Edward Stafford wrote a letter in which he referred to 'My rotten castle of Stafford.'

During the early phases of the Civil War it was defended by Lady Isobel, a staunch Roman Catholic and Royalist. The Parliamentarians had captured Stafford on 15 May 1643, following a brief siege, but some of its garrison escaped and held Stafford Castle, with the hope of using it as a bridgehead to recapture the town.

Colonel Brereton rode up to the castle with some of his men and called upon Lady Stafford to surrender, which she refused. In response 'some of the poor outhouses were set on fire to try whether these would work their spirits to any relenting. All in vain, for from the castle they shot some of our men and horses which did much enrage and provoke the rest to a fierce revenge. Almost all the dwelling houses and outhouses were burnt to the ground.'

The siege was raised when Colonel Hastings led a relief column which arrived on 5 June. Lady Isobel was eventually persuaded to leave, a small garrison remaining to defend the castle against a renewed siege. Finally, in late June, the Royalist garrison fled, having heard of information that a large Parliamentarian army was approaching, complete with a number of siege cannons capable of easily overwhelming the small garrison that remained. The castle then fell into Parliamentarian control in which it stayed until its demolition.

On 22 December, not many months after its capture, the Parliamentarian Committee of Stafford, ordered: 'the Castle shall be forthwith demolished.' The order was carried-out with the loss of a crowbar!

When the traveller and diarist, Celia Fiennes passed through the county town in 1698, she noted:

'...the castle which is now ruinated and there only remains on a hill the fortified trenches that are grown over green.'

Victorian[]

The interior of the rebuilt keep

The castle was partly rebuilt in the Gothic Revival Style from 1813, but work was discontinued partly through the lack of funds, but also because the Jerningham family were elevated to the peerage (one of their motives for the restoration project). Dubbed by some as a folly, this was never the case, as the Keep was always intended to be lived in, and was occupied well into the 20th century.[3] It is a Grade II listed building.[3] It is open to visitors and visible from the M6 motorway.

From the Victorian era, the Keep was occupied by caretakers. Many Staffordians can remember the last caretakers, Mr and Mrs Stokes, who used to give tours of the structure and served cups of tea and home-make cakes for 3d. In winter Mr and Mrs Stokes used buy produce from the local farms and drag it up the drive on a sledge. One local recalled that he and his friends visited the Keep in mid-winter but Mrs Stokes wasn't too keen on taking them around and they were sent away - the boys used the sledge to speed off down the drive. Another boy tied a 'Stafford Knot' in the lead water pipe which used to be at the bottom of the drive - evidently the 40's was a time of 'creative vandalism'.

Modern[]

In the immediate post-war years the mature woodland that surrounded the Keep was felled, which may have led to the structure being exposed to high winds. By 1949 large pieces of masonry had begun to fall from the towers, which were declared unsafe. Mr and Mrs Stokes, the last caretakers of the castle and its grounds, vacated the building that winter. Sadly the site became a target for vandals and in 1961 Lord Stafford gave the Keep to the local authority. Not long afterwards a boy was killed when he fell from the unsafe South Front. In 1962 the towers and the remainder of the North Wing were reduced to the height of the North Front and made safe. Many people still believed that the Castle was a Georgian folly, although local historians were aware not only of its history but also that of the Stafford family. In 1978 excavations began to reveal the complex archaeology of the site, which had been for generations the seat of one of the most important families in the region. A heritage trail was established in 1988, while three years on a purpose-built museum and gift shop opened on-site.

Every summer events are performed in the grounds of the Castle, the most popular of which is the annual showing of various Shakespeare plays.

See also[]

References[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Darlington, John; Soden, Iain (2007). "Disscussion". In Soden Allen, Iain. Stafford Castle Survey, Excavation and Research 1978-1998 Volume II The excavations. Stafford Borough Council. pp. 190–191. ISBN 9780952413639.

- ↑ http://www.staffordhistory.co.uk/stafford-castle/

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Heritage Gateway

External links[]

- CastleUk

- Stafford Historys article on Stafford Castle (staffordhistory.co.uk/stafford-castle)

- Stafford Castle (staffordtown.co.uk)

- Stafford Castle and Visitor Centre - official site and visiting information

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stafford Castle. |

The original article can be found at Stafford Castle and the edit history here.