Rise and Fall of the Ottoman Empire 1300–1923

1300[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1300

The origins of the Ottomans can be traced back to the late 11th century when a few small Muslim emirates of Turkic origins and nomadic nature—called Beyliks—started to be founded in different parts of Anatolia. Their main role was to defend Seljuk border areas with the Byzantine Empire —a role reinforced by the migration of many Turks to Asia Minor.[1] However, in 1073 and following the victory of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm over the Byzantines at the Battle of Manzikert, Beyliks sought an opportunity to override the Seljuk authority and declare their own sovereignty openly.

While the Byzantine Empire was to continue for nearly another four centuries, and the Crusades would contest the issue for some time, the victory at Manzikert signalled the beginning of Turkic ascendancy in Anatolia. The subsequent weakening of the Byzantine Empire and the political rivalry between the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm and the Fatimid in Egypt and southern Syria were the main factors that helped the Beyliks take advantage of the situation and unite their principalities.[2]

Among those principalities was a tribe called Söğüt, founded and led by Ertuğrul, which settled in the river valley of Sakarya. When Ertuğrul died in 1281, his son Osman became his successor. Shortly thereafter, Osman declared himself a Sultan and established the Ottoman Dynasty, becoming the first Sultan of the Ottoman Empire in 1299.[3]

1359[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1359

Murad I (nicknamed Hüdavendigâr – from Persian: خداوندگار Khodāvandgār – "the God-like One") (Turkish language: I. Murat Hüdavendigâr) (March or June 29, 1326, Sogut or Bursa – June 28, 1389, Battle of Kosovo) (Ottoman Turkish language: مراد الأول) was the ruler of the Ottoman Empire, Sultan of Rûm, from 1359 to 1389. He was the son of Orhan I and the Valide Sultan Nilüfer Hatun (whose name means Water lily in Turkish), daughter of the Prince of Yarhisar or Byzantine Princess Helen (also named Nilüfer), who was of ethnic Greek descent[4][5][6] and became the ruler following his father's death in 1359.

1451[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1451

Mehmet II (Ottoman Turkish: محمد الثانى Meḥmed-i sānī, Turkish language: II. Mehmet), (also known as el-Fatih (الفاتح), "the Conqueror", in Ottoman Turkish, or, in modern Turkish, Fatih Sultan Mehmet) (March 30, 1432, Edirne – May 3, 1481, Hünkârcayırı, near Gebze) was Sultan of the Ottoman Empire (Rûm until the conquest) for a short time from 1444 to September 1446, and later from February 1451 to 1481. At the age of 21, he conquered Constantinople, bringing an end to the Byzantine Empire.

1481[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1481

Selim I (Ottoman Turkish: سليم اوّل, Modern Turkish: I. Selim) also known as "the Grim" or "the Brave", or the best translation "the Stern", Yavuz in Turkish, the long name is Yavuz Sultan Selim; (October 10, 1465/1466/1470 – September 22, 1520) was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520.[7]

Selim's father was Bayezid II and his mother was Ayşe Hatun, from Dulkadirids.

Selim carried the empire to the leadership of the Sunni branch of Islam by his conquest of the Middle East. He represents a sudden change in the expansion policy of the empire, which was working mostly against the West and the Beyliks before his reign.[8] On the eve of his death in 1520, the Ottoman empire spanned almost 1,000 million acres (4,000,000 km2) (trebling during Selim's reign).

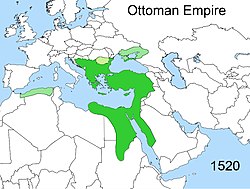

1520[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1520

Suleiman I (Ottoman Turkish language: سليمان Sulaymān, Turkish language: Süleyman; almost always Kanuni Sultan Süleyman) (April 27, 1494/1495/6 November 1494 – 5/6/7 September 1566), was the tenth and longest-reigning Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, from 1520 to his death in 1566. He is known in the West as Suleiman the Magnificent[9] and in the East, as the Lawgiver (in Turkish Kanuni; Arabic language: القانونى, al‐Qānūnī), for his complete reconstruction of the Ottoman legal system. Suleiman became a prominent monarch of 16th century Europe, presiding over the apex of the Ottoman Empire's military, political and economic power. Suleiman personally led Ottoman armies to conquer the Christian strongholds of Belgrade, Rhodes, and most of Hungary before his conquests were checked at the Siege of Vienna in 1529. He annexed most of the Middle East in his conflict with the Persians and large swathes of North Africa as far west as Algeria. Under his rule, the Ottoman fleet dominated the seas from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf.[10]

At the helm of an expanding empire, Suleiman personally instituted legislative changes relating to society, education, taxation, and criminal law. His canonical law (or the Kanuns) fixed the form of the empire for centuries after his death. Not only was Suleiman a distinguished poet and goldsmith in his own right; he also became a great patron of culture, overseeing the golden age of the Ottoman Empire's artistic, literary and architectural development.[11]

In a break with Ottoman tradition, Suleiman married (as his fourth wife) a harem girl, Roxelana, who became Hürrem Sultan; her intrigues as queen in the court and power over the Sultan have become as famous as Suleiman himself. Their son, Selim II, succeeded Suleiman following his death in 1566 after 46 years of rule.

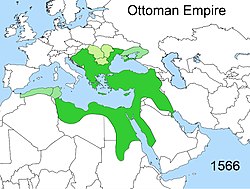

1566[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1566

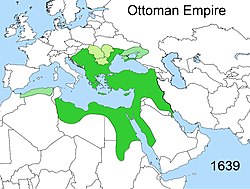

1639[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1639

The Treaty of Zohab (or the Treaty of Qasr-e-Shirin) was an accord signed between Safavid Persia and the Ottoman Empire on May 17, 1639. This accord ended the war that had begun in 1623 and was the last conflict in almost 150 years of intermittent wars between the two states over territorial disputes. The treaty divided territories in the Middle East by granting Yerevan in the southern Caucasus to Iran and all of Mesopotamia (including Baghdad) to the Ottomans.

1672[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1672

Apart from an Ottoman occupation (1672–1699), the Poles retained Podolia until the partitions of their country in 1772 and 1793, when the Habsburg Monarchy of Austria and Imperial Russia annexed the western and eastern parts respectively.

1683[]

The Treaty of Bakhchisarai was signed in Bakhchisaray after the Russo-Turkish War (1676–1681) on January 3, 1681 by Russia, the Ottoman Empire, and the Crimean Khanate. They agreed to a 20-year truce and had accepted the Dnieper River as the demarcation line between the Ottoman Empire and Moscow's domain. All sides agreed not to settle the territory between the Southern Buh and Dnieper rivers. After the signing of the treaty, the Nogai hordes still retained the right to live as nomads in the southern steppes of Ukraine, while the Cossacks retained the right to fish in the Dnieper and its tributaries; to obtain salt in the south; and to sail on the Dnieper and the Black Sea. The sultan then recognized Muscovy's sovereignty in the Left-bank Ukraine region and the Zaporozhian Cossack domain, while the southern part of the Kiev region, the Bratslav region, and Podolia were left under Ottoman control.

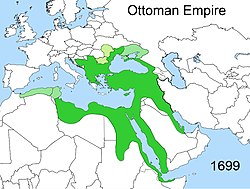

1699[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1699

The Treaty (Peace) of Karlowitz (Karlovci) was signed on January 26, 1699 in Sremski Karlovci (Serbian Cyrillic: Сремски Карловци, Croatian: Srijemski Karlovci, German: Karlowitz, Turkish: Karlofça, Hungarian: Karlóca), a town in modern-day Serbia, concluding the Austro-Ottoman War of 1683–1697 in which the Ottoman side had finally been defeated at the Battle of Zenta.

Following a two-month congress between the Ottoman Empire on one side and the Holy League of 1684, a coalition of various European powers including the Habsburg Monarchy, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Republic of Venice and Peter I's Alekseyevich (later known as The Great) Muscovite Russia, largely due to claims of being a self-professed defender of the Christian Slavs, a treaty was signed on January 26, 1699. The Ottomans ceded most of Hungary, Transylvania and Slavonia to Austria while Podolia returned to Poland. Most of Dalmatia passed to Venice, along with the Morea (the Peloponnesus peninsula) and Crete, which the Ottomans regained in the Treaty of Passarowitz of 1718.

1718[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1718

The Treaty of Passarowitz or Treaty of Požarevac was the peace treaty signed in Požarevac (Serbian Cyrillic: Пожаревац, German: Passarowitz, Turkish: Pasarofça, Hungarian: Pozsarevác), a town in modern Serbia, on July 21, 1718 between the Ottoman Empire on one side and the Habsburg Monarchy of Austria and the Republic of Venice on the other.

During the years 1714–1718, the Ottomans had been successful against Venice in Greece and Crete, but had been defeated at Petrovaradin (1716) by the Austrian troops of Prince Eugene of Savoy.

The treaty reflected the military situation. The Ottoman Empire lost the Banat of Temeswar, over a half of the territory of Serbia (from Belgrade to south of Kruševac), a tiny strip of northern Bosnia and Lesser Walachia (Oltenia) to Austria. Venice lost its possessions on the Peloponnesus peninsula and on Crete, gained by the Treaty of Karlowitz, retaining only the Ionian Islands, cities of Preveza and Arta and Dalmatia. Northern Bosnia, Serbia including Belgrade and Lesser Walachia were regained by Ottoman Empire in 1739 by the Treaty of Belgrade.

1739[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1718

- The Treaty of Belgrade (Russian: Белградский мир) was the peace treaty signed on September 18, 1739 in Belgrade, Serbia, by the Ottoman Empire on one side and the Habsburg Monarchy on the other. This ended the hostilities of the two-year Austro-Turkish War, 1737-39, in which the Habsburgs joined Imperial Russia in its fight against the Ottomans. With the Treaty of Belgrade, the Habsburgs ceded Northern Serbia with Belgrade to the Ottomans, and Oltenia, gained by the Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718, to Wallachia (an Ottoman subject), and set the demarcation line to the rivers Sava and Danube. The Habsburg withdrawal forced Russia to accept peace at the Russo-Turkish War, 1735-1739 with the Treaty of Nissa, whereby it was allowed to build a port at Azov, gaining a foothold on the Black Sea.[12]

- The Treaty of Niš is a peace treaty signed on October 3, 1739 in Nissa (ancient Nyssa, in Cappadocia) by the Ottoman Empire on one side and Russian Empire on the other. The Russo-Turkish War, 1735-1739 was the result of the Russian effort to gain Azov and Crimea as a first step towards dominating the Black Sea. In several successful raids led by Marshal Munich, the Russians broke the resistance of the Crimean Khanate, crossed the Dniester into Moldavia and in 1739 marched as far as the Moldavian capital of Iaşi (Jassy), which they captured. The Habsburg Monarchy entered the war in 1737 on the Russian side to get its share, but was forced to make peace with Ottomans at the separate Treaty of Belgrade, surrendering Northern Serbia, Northern Bosnia and Oltenia, and allowing the Ottomans to resist the Russian push toward Istanbul. In return, the Sultan acknowledged the Habsburg Emperor as the official protector of all Ottoman Christian subjects (see Ottoman millet), a position also claimed by Russia. The Austrian pullout forced Russia to accept peace at Niš, giving up its claims to Crimea and Moldavia, being allowed to build a port at Azov but not to build fortifications there or have any fleet in the Black Sea.

1774[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1774

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (also spelled Kuchuk Kainarji) was signed on July 21, 1774, in Küçük Kaynarca, Dobruja (today Kaynardzha, Silistra Province, Bulgaria) between the Russian Empire (represented by Field-Marshal Rumyantsev) and the Ottoman Empire after the Ottoman Empire was defeated in the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774.[13]

The treaty was by far the most humiliating blow to the once-mighty Ottoman realm. The Ottomans ceded the part of the Yedisan region between the Dnieper and Southern Bug rivers to Russia. This territory included the port of Kherson and gave the Russian Empire its first direct access to the Black Sea. The treaty also gave Russia the Crimean ports of Kerch and Enikale and the Kabarda region in the Caucasus.

The Ottomans also lost the Crimean Khanate, to which they were forced to grant independence. The Khanate, while nominally independent, was dependent on Russia and was formally annexed into the Russian Empire in 1783. The treaty also granted Russia several non-geographic items. It eliminated restrictions over Russian access to the Azov Sea (the 1739 Treaty of Belgrade had given Russia territory adjacent to the Azov Sea but had prohibited it from fortifying the area or using the sea for shipping.)

1783[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1783

The Treaty of Georgievsk (Russian: Георгиевский трактат, Georgievskiy traktat; Georgian language: გეორგიევსკის ტრაქტატი , georgievskis trak'tati) was a bilateral treaty concluded between the Russian Empire and the east Georgian kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti on July 24, 1783. The treaty established Georgia as a protectorate of Russia, which guaranteed Georgia's territorial integrity and the continuation of its reigning Bagrationi dynasty in return for prerogatives in the conduct of Georgian foreign affairs. Georgia abjured any form of dependence on Persia or another power, and every new Georgian monarch would require the confirmation and investiture of the Russian tsar.

1792[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1792

The Treaty of Jassy, signed at Jassy (Iaşi) in Moldavia (presently in Romania), was a pact between the Russian and Ottoman Empires ending the Russo-Turkish War of 1787–92 and confirming Russia's increasing dominance in the Black Sea. The treaty was signed on January 9, 1792 by Grand Vizier Yusuf-Pasha and Prince Bezborodko (who had succeeded Prince Potemkin as the head of the Russian delegation when Potemkin died). The treaty recognized Russia's 1783 annexation of the Crimean Khanate and transferred Yedisan to Russia making the Dniester the Russo-Turkish frontier in Europe, and leaving the Asiatic frontier (Kuban River) to the East.

1798[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1798

Led by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798 France invaded Egypt while they were forced to leave in 1800 they had a great social impact on the country and its culture.

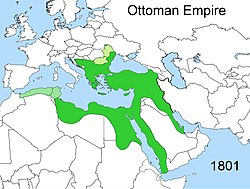

1801[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1801

The Turks struggle to hold onto Egypt against a civil war between the Albanians, Mamelukes, and Turks.

1812[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1812

The Treaty of Bucharest between the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire, was signed on May 28, 1812 in Bucharest at the end of the Russo-Turkish War, 1806-1812. Under its terms, the Prut River became the border between the two empires, thus leaving Bessarabia under Russian rule. Also, Russia obtained trading rights on the Danube. A truce was signed with the rebelling Serbs and autonomy given to Serbia. The treaty, signed by the Russian commander Mikhail Kutuzov, was ratified by Alexander I of Russia just one day before Napoleon launched his invasion of Russia.

1817[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1817

The Second Serbian Uprising (1815–1817) was a second phase of the Serbian revolution against the Ottoman Empire, which erupted shortly after the re-annexation of the country to the Ottoman Empire, in 1813. The occupation was enforced following the defeat of the First Serbian Uprising (1804–1813), during which Serbia existed as a de facto independent state for over a decade. The second revolution ultimately resulted in Serbian semi-independence from the Ottoman Empire. Principality of Serbia was established, governed by its own Parliament, Constitution and its own royal dynasty. De jure independence followed during the second half of the 19th century.

1829[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1829

- The creation of a separate Greek state, albeit under Ottoman suzerainty and owing an annual tribute, was recognized by the Great Powers in the London Protocol.

- The 1829 Treaty of Adrianople, without overturning Ottoman suzerainty, placed Wallachia and Moldavia under Russian military rule, awarding them the first common institutions and the semblance of a constitution. The Treaty of Adrianople also gave Russia most of the eastern shore of the Black Sea and the whole delta of or mouth of the Danube River. Turkey recognized Russian sovereignty over Georgia and parts of present-day Armenia.

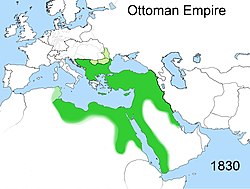

1830[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1830

- Greece was recognized as a fully independent and sovereign kingdom in the London Protocol.

- During the Directory regime of the First French Republic (1795–1799), the Bacri and the Busnach, Jewish negotiants of Libourne, provided important quantities of grain for Napoleon's soldiers who participated in the Italian campaign of 1796. However, Bonaparte refused to pay the bill back, claiming it was excessive. In 1820, Louis XVIII paid back half of the Directory's debts. The dey, who had loaned to the Bacri 250,000 francs, requested from France the rest of the money.

But another, more serious matter enraged the Dey. France had the commercial concession of a stockhouse in La Calle, and, by the intermediary of its representant Deval, had engaged itself not to fortify it. However, Paris did not respect its engagements. The dey first requested explanations by sending a letter to the French government, who chose not to respond him. Thus, the dey orally asked the reasons behind this disrespect of their conventions to the French consul, who refused to respond to him.

The dey responded to French disdain by hitting the consul Deval with his fan on April 30, 1827. This led to the rupture of diplomatic relations between France and the Dey, although the financial dealings between Deval and the Bacri-Busnach, as well as the Calle fortifications affairs were the real causes of the hostility.

Thereafter, the government of Charles X (1824–1830) took the "fan affair" ("l'affaire de l'éventail") as a pretext to invade Algeria and castigate the Dey for his "impudence." The French consul and residents took off for France, while the Minister of War, Clermont-Tonnerre, proposed a military expedition. The ultra-royalist Count of Villèle, President of the Council, and the monarch's heir opposed themselves to it. The Restoration finally decided to blockade Algiers for three years. But the important tonnage of French ships forced them to keep away from the coasts[vague] , while the Barbary pilots could easily exploit the geography of the coast. Before the failure of the blockade, the Restoration decided on January 31, 1830 to engage a military expedition against Algiers.

The French troops took the advantage on June 19, during the battle of Staoueli, and entered in Algiers on July 5, 1830, after a three-week campaign. The Dey Hussein accepted capitulation in exchange of his freedom and the offer to retain possession of his personal wealth. Five days later, he exiled himself with his family, on board of a French ship heading for the Italian peninsula, then under the control of the Austrian Empire. 2,500 janissaries also quit the Algerian territories, heading for Asia, on July 11,. After 313 years of occupation, the Ottomans abandoned the Regency in Algiers and therefore the administration of the country, which they had taken care of since 1517.

1856[]

The Crimean War (1853–1856) was fought between Imperial Russia on one side and an alliance of France, the United Kingdom, the Kingdom of Sardinia, and the Ottoman Empire on the other. Most of the conflict took place on the Crimean Peninsula, with additional actions occurring in western Turkey, and the Baltic Sea region.

1859[]

The electors in both Moldavia and Wallachia chose in 1859 the same person – Alexandru Ioan Cuza.

1862[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1862

On February 5, 1862 (January 24, Old Style) the two principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia were formally united to form Romania, with Bucharest as its capital.

1878[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1878

Ending the Russo-Turkish War, 1877–78 the Treaty of Berlin was the final Act of the Congress of Berlin (June 13 – July 13, 1878), by which the United Kingdom, Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, Russia and the Ottoman Empire under Abdul Hamid II revised the Treaty of San Stefano signed on March 3, of the same year.

The treaty recognized the complete independence of the principalities of Romania, Serbia and Montenegro and the autonomy of Bulgaria, though the latter remained under formal Ottoman overlordship and was divided between the Principality of Bulgaria and the autonomous province of Eastern Rumelia. The Western Great Powers immediately rejected the Treaty of San Stefano: they feared that a large Slavic country in the Balkans would serve Russian interests. Most of northern Thrace was included in the autonomous region of Eastern Rumelia, whereas the rest of Thrace and all of Macedonia were returned under the sovereignty of the Ottomans.

1881[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1881

- In the spring of 1881, the French army occupied Tunisia, claiming that Tunisian troops had crossed the border to Algeria, France's primary colony in Northern Africa. Italy, also interested in Tunisia, protested, but did not risk a war with France. On May 12, of that year, Tunisia was officially made a French protectorate with the signature of the Treaty of Bardo by Muhammad III as-Sadiq.

- In 1881 the Ottoman Empire ceded most of Thessaly and parts of southern Epirus (the Arta Prefecture) to Greece

1882[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1882

With Egypt heading towards bankruptcy, the United Kingdom seized control of Egypt's government in 1882 to protect its financial interests, especially those in the Suez Canal. Shortly after its political intervention, Britain sent troops into Alexandria and the Canal Zone, taking advantage of Egypt's weak military. With the defeat of the Egyptian army at the Battle of Tel el-Kebir, British troops reached Cairo, eliminated the nationalist government and disbanded the Egyptian military. Technically, Egypt remained an Ottoman province until 1914, when Britain formally declared a protectorate over Egypt and deposed Egypt's last khedive, Abbas II. His uncle, Husayn Kamil, was appointed as Sultan in his place. But in reality Egypt was lost to the Turks.

1908[]

The Young Turk revolution resulted in the loss of the Ottoman province of Bosnia to Austria-Hungary (which at any rate had militarily occupied Bosnia since 1878), the tributary Principality of Bulgaria declared independence from the Ottoman Empire. Bulgaria simultaneously annexed the autonomous Ottoman Province of Eastern Rumelia (of which the Prince of Bulgaria had been Governor-General since 1885.).

1912[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1912

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War (also known in Italy as guerra di Libia, "the Libyan war", and in Turkey as Trablusgarp Savaşı) was fought between the Ottoman Empire and Italy from September 29, 1911 to October 18, 1912. Italy seized the Ottoman provinces of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, together forming what became known as Libya, as well as the Isle of Rhodes and the Greek-speaking Dodecanese archipelago near Anatolia. Following the First Balkan War, the Autonomous Principality of Samos, an Ottoman tributary state, was annexed to Greece in November 1912.

1913[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1913

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1913

The Balkan Wars were two wars in South-eastern Europe in 1912–1913 in the course of which the Balkan League (Bulgaria, Montenegro, Greece, and Serbia) first conquered Ottoman-held Macedonia, Albania and most of Thrace and then fell out over the division of the spoils.

After the Second Balkan War, the Ottomans were removed from Albania and there was a possibility of some of the lands being absorbed by Serbia and the southern tip by Greece. This decision angered the Italians, who did not want Serbia to have an extended coastline, and it also angered the Austro-Hungarians, who did not want a powerful Serbia on their southern border. Despite Serbian, Montenegrin, and Greek occupation forces on the ground, and under immense pressure from Austria-Hungary, it was decided that the country should not be divided but instead consolidated into the Principality of Albania. In the aftermath of Balkan wars Crete joined Greece on December 1, 1913.

1914[]

Following the Ottoman declaration of war on the Allies in November 1914, Britain formally annexed Cyprus, which it had occupied since 1878. Egypt (along with the Sudan) also finally ceased to be de jure Ottoman territory at the same time, being elevated to a Sultanate.

1920[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1920

The Treaty of Sèvres (August 10, 1920) was the peace treaty between the Ottoman Empire and Allies at the end of World War I. The Treaty of Versailles was signed with Germany before this treaty to annul the German concessions including the economic rights and enterprises. Also, France, Great Britain and Italy signed a secret "Tripartite Agreement" at the same date.[14] The Tripartite Agreement confirmed Britain's oil and commercial concessions and turned the former German enterprises in the Ottoman Empire over to a Tripartite corporation. The open negotiations covered a period of more than fifteen months, beginning at the Paris Peace Conference. The negotiations continued at the Conference of London, and took definite shape only after the premiers' meeting at the San Remo conference in April 1920. France, Italy, and Great Britain, however, had secretly begun the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire as early as 1915. The delay was due to the fact that the powers could not come to an agreement which, in turn, hinged on the outcome of the Turkish national movement. The Treaty of Sèvres was annulled in the course of the Turkish War of Independence and the parties signed and ratified the superseding Treaty of Lausanne in 1923.

1923[]

Territorial changes of the Ottoman Empire 1923

The Treaty of Lausanne (July 24, 1923) was a peace treaty signed in Lausanne, Switzerland, that settled the Anatolian and East Thracian parts of the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire by annulment of the Treaty of Sèvres (1920) that was signed by the Istanbul-based Ottoman government; as the consequence of the Turkish War of Independence between the Allies of World War I and the Ankara-based Grand National Assembly of Turkey (Turkish national movement) led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. The treaty also led to the international recognition of the sovereignty of the new Republic of Turkey as the successor state of the defunct Ottoman Empire.[15]

See also[]

References[]

- ↑ Malcolm Holt, Peter; Ann K. S. Lambton, Bernard Lewis (1977). The Cambridge History of Islamy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 231–232. ISBN 978-0-521-29135-4.

- ↑ Kural Shaw, Ezel (1977). History of the Ottoman Empire and modern Turkey. Cambridge University Press. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-0-521-29163-7.

- ↑ Bideleux, Robert; Ian Jeffries (1998). A history of eastern Europe: crisis and change. Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-415-16111-4.

- ↑ The Fall of Constantinople, Steven Runciman, Cambridge University Press, p.36

- ↑ The Nature of the Early Ottoman State, Heath W. Lowry, 2003 SUNY Press, p.153

- ↑ History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, Stanford Jay Shaw, Cambridge University Press, p.24

- ↑ Yavuz Sultan Selim Biography Retrieved 2007-09-16[dead link]

- ↑ The Rise of the Turks and the Ottoman Empire Retrieved 2007-09-16

- ↑ Merriman, Roger Bigelow (1944). Suleiman the Magnificent, 1520–1566. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. OCLC 784228.

- ↑ Page 61. – Mansel, Phillip (1998). Constantinople : City of the World's Desire, 1453–1924. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-18708-8.

- ↑ Pg 24 – Atıl, Esin (1987). The Age of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. ISBN 978-0-89468-098-4.

- ↑ Henry Smith Williams (1909). The Historians' History of the World. Hooper and Jackson LTD. p. 410.

- ↑ Ömer Lütfi Barkan (1985). Ord. Prof. Ömer Lütfi Barkan'a armağan. Istanbul University. p. 48.

- ↑ The Times (London), 27. Idem., Jan 30, 1928, Editorial.

- ↑ Full text of the Treaty of Lausanne (1923)

The original article can be found at Territorial evolution of the Ottoman Empire and the edit history here.