Persia at the beginning of the Great Game in 1814

Central Asia, circa 1848

The Great Game was a term for the strategic rivalry and conflict between the British Empire and the Russian Empire for supremacy in Central Asia.[1] The classic Great Game period is generally regarded as running approximately from the Russo-Persian Treaty of 1813 to the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907. A less intensive phase followed the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. In the post-Second World War post-colonial period, the term has continued in use to describe the geopolitical machinations of the Great Powers and regional powers as they vie for geopolitical power and influence in the area.[2][3]

The term "The Great Game" is usually attributed to Arthur Conolly (1807–1842), an intelligence officer of the British East India Company's Sixth Bengal Light Cavalry.[4] It was introduced into mainstream consciousness by British novelist Rudyard Kipling in his novel Kim (1901).[5]

British-Russian rivalry in Afghanistan[]

From the British perspective, the Russian Empire's expansion into Central Asia threatened to destroy the "jewel in the crown" of the British Empire, British India. The British feared that the Tsar's troops would subdue the Central Asian khanates (Khiva, Bokhara, Khokand) one after another. The Emirate of Afghanistan might then become a staging post for a Russian invasion of India.[6]

It was with these thoughts in mind that in 1838 the British launched the First Anglo-Afghan War and attempted to impose a puppet regime on Afghanistan under Shuja Shah. The regime was short lived and proved unsustainable without British military support. By 1842, mobs were attacking the British on the streets of Kabul and the British garrison was forced to abandon the city due to constant civilian attacks.

The retreating British army consisted of approximately 4,500 troops (of which only 690 were European) and 12,000 camp followers. During a series of attacks by Afghan warriors, all Europeans but one, William Brydon, were killed on the march back to India; a few Indian soldiers survived also and crossed into India later.[7] The British curbed their ambitions in Afghanistan following this humiliating retreat from Kabul.

Lake Zorkul, Pamirs, 1874, watercolor by British Army officer Thomas Edward Gordon

After the Indian rebellion of 1857, successive British governments saw Afghanistan as a buffer state. The Russians, led by Konstantin Kaufman, Mikhail Skobelev, and Mikhail Chernyayev, continued to advance steadily southward through Central Asia towards Afghanistan, and by 1865 Tashkent had been formally annexed.

Samarkand became part of the Russian Empire in 1868, and the independence of Bukhara was virtually stripped away in a peace treaty the same year. Russian control now extended as far as the northern bank of the Amu Darya river.

In a letter to Queen Victoria, Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli proposed "to clear Central Asia of Muscovites and drive them into the Caspian".[8] He introduced the Royal Titles Act 1876, which added to Victoria's titles that of Empress of India, putting her at the same level as the Russian Emperor.

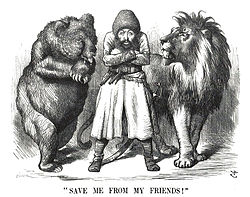

Political cartoon depicting the Afghan Emir Sher Ali with his "friends" the Russian Bear and British Lion (1878)

After the Great Eastern Crisis broke out and the Russians sent an uninvited diplomatic mission to Kabul in 1878, Britain demanded that the ruler of Afghanistan, Sher Ali, accept a British diplomatic mission. The mission was turned back, and in retaliation a force of 40,000 men was sent across the border, launching the Second Anglo-Afghan War. The war's conclusion left Abdur Rahman Khan on the throne, and he agreed to let the British control Afghanistan's foreign affairs, while he consolidated his position on the throne. He managed to suppress internal rebellions with ruthless efficiency and brought much of the country under central control.

In 1884, Russian expansionism brought about another crisis – the Panjdeh Incident – when they seized the oasis of Merv. The Russians claimed all of the former ruler's territory and fought with Afghan troops over the oasis of Panjdeh. On the brink of war between the two great powers, the British decided to accept the Russian possession of territory north of the Amu Darya as a fait accompli.

Without any Afghan say in the matter, between 1885 and 1888 the Joint Anglo-Russian Boundary Commission agreed the Russians would relinquish the farthest territory captured in their advance, but retain Panjdeh. The agreement delineated a permanent northern Afghan frontier at the Amu Darya, with the loss of a large amount of territory, especially around Panjdeh.[9]

This left the border east of Zorkul lake in the Wakhan. Territory in this area was claimed by Russia, Afghanistan and China. In the 1880s the Afghans advanced north of the lake to the Alichur Pamir.[10] In 1891, Russia sent a military force to the Wakhan and provoked a diplomatic incident by ordering the British Captain Francis Younghusband to leave Bozai Gumbaz in the Little Pamir. This incident, and the report of an incursion by Russian Cossacks south of the Hindu Kush, led the British to suspect Russian involvement "with the Rulers of the petty States on the northern boundary of Kashmir and Jammu".[11] This was the reason for the Hunza-Nagar Campaign in 1891, after which the British established control over Hunza and Nagar. In 1892 the British sent the Earl of Dunmore to the Pamirs to investigate. Britain was concerned that Russia would take advantage of Chinese weakness in policing the area to gain territory, and in 1893 reached agreement with Russia to demarcate the rest of the border, a process completed in 1895.[10]

Great Game moves eastward[]

People of Central Asia c.1861–1880

By the 1890s, the Central Asian khanates of Khiva, Bukhara and Kokand had fallen, becoming Russian vassals. With Central Asia in the Tsar's grip, the Great Game now shifted eastward to China, Mongolia and Tibet. In 1904, the British invaded Lhasa, a pre-emptive strike against Russian intrigues and secret meetings between the 13th Dalai Lama's envoy and Tsar Nicholas II. The Dalai Lama fled into exile to China and Mongolia. The British were greatly concerned at the prospect of a Russian invasion of the Crown colony of India, though Russia – badly defeated by Japan in the Russo-Japanese war and weakened by internal rebellion – could not realistically afford a military conflict against Britain. China under the Qing Dynasty, however, was another matter.[12]

The Middle Kingdom had badly atrophied under the Manchus, the ruling ethnic caste of the Qing Dynasty. Two-and-a-half centuries of decadent living, internecine feuds and imperviousness to a changing world had weakened the Empire. China’s weaponry and military tactics were outdated, even medieval. Modern factories, steel bridges, railways and telegraphs were almost nonexistent in most regions. Natural disasters, famine and internal rebellions had further enfeebled China. In the late 19th century, Japan and the Great Powers easily carved out trade and territorial concessions. These were humiliating submissions for the once all-powerful Manchus. Still, the central lesson of the war with Japan was not lost on the Russian General Staff: an Asian country using Western technology and industrial production methods could defeat a great European power.[13]

In 1906, Tsar Nicholas II sent a secret agent to China to collect intelligence on the reform and modernization of the Qing Dynasty. The task was given to Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim, at the time a colonel in the Russian army, who travelled to China with French sinologist Paul Pelliot. Mannerheim was disguised as an ethnographic collector, using a Finnish passport.[13] Finland was, at the time, a Grand Duchy. For two years, Mannerheim proceeded through Xinjiang, Gansu, Shaanxi, Henan, Shanxi and Inner Mongolia to Beijing. At the sacred Buddhist mountain of Wutai Shan he even met the 13th Dalai Lama.[14] However, while Mannerheim was in China in 1907, Russia and Britain brokered the Anglo-Russian Agreement, ending the classical period of the Great Game.

Anglo-Russian Alliance[]

In the run-up to World War I, both empires were alarmed by the unified German Empire's increasing activity in the Middle East, notably the German project of the Baghdad Railway, which would open up Mesopotamia and Persia to German trade and technology. The ministers Alexander Izvolsky and Edward Grey agreed to resolve their long-standing conflicts in Asia in order to make an effective stand against the German advance into the region. The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 brought a close to the classic period of the Great Game.

The borders of the Russian imperial territories of Khiva, Bukhara and Kokand in the time period of 1902–1903

The Russians accepted that the politics of Afghanistan were solely under British control as long as the British guaranteed not to change the regime. Russia agreed to conduct all political relations with Afghanistan through the British. The British agreed that they would maintain the current borders and actively discourage any attempt by Afghanistan to encroach on Russian territory. Persia was divided into three zones: a British zone in the south, a Russian zone in the north, and a narrow neutral zone serving as buffer in between.[15]

In regards to Tibet, both powers agreed to maintain territorial integrity of this buffer state and "to deal with Lhasa only through China, the suzerain power".[16]

A less intensive British-Soviet rivalry[]

Caption from a 1911 English satirical magazine reads: "If we hadn't a thorough understanding, I (British lion) might almost be tempted to ask what you (Russian bear) are doing there with our little playfellow (Persian cat)."

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 nullified existing treaties and a second phase of the Great Game began. The Third Anglo-Afghan War of 1919 was precipitated by the assassination of the then ruler Habibullah Khan. His son and successor Amanullah declared full independence and attacked the northern frontier of British India. Although little was gained militarily, the stalemate was resolved with the Rawalpindi Agreement of 1919. Afghanistan re-established its self-determination in foreign affairs.

In May 1921, Afghanistan and the Russian Soviet Republic signed a Treaty of Friendship. The Soviets provided Amanullah with aid in the form of cash, technology and military equipment. British influence in Afghanistan waned, but relations between Afghanistan and the Russians remained equivocal, with many Afghans desiring to regain control of Merv and Panjdeh. The Soviets, for their part, desired to extract more from the friendship treaty than Amanullah was willing to give.

The United Kingdom imposed minor sanctions and diplomatic slights as a response to the treaty, fearing that Amanullah was slipping out of their sphere of influence and realising that the policy of the Afghanistan government was to have control of all of the Pashtun speaking groups on both sides of the Durand Line. In 1923, Amanullah responded by taking the title padshah – "emperor" – and by offering refuge for Muslims who fled the Soviet Union, and Indian nationalists in exile from the Raj.

Amanullah's programme of reform was, however, insufficient to strengthen the army quickly enough; in 1928 he abdicated under pressure. The individual who most benefited from the crisis was Mohammed Nadir Shah, who reigned from 1929 to 1933. Both the Soviets and the British played the situation to their advantage: the Soviets getting aid in dealing with Uzbek rebellion in 1930 and 1931, while the British aided Afghanistan in creating a 40,000 man professional army.

With the German invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941 during World War II came the temporary alignment of British and Soviet interests. Both governments pressured Afghanistan for the expulsion of a large German non-diplomatic contingent, which they believed to be engaging in espionage. Afghanistan immediately complied. A period of win-win cooperation continued between the USSR and UK against Nazi Germany until the end of the war in 1945. This less intensive second phase of the Great Game would enter a new era owing to post WW2 geopolitical changes.

Cold War[]

After the success of the temporary Second World War alliance among the Allied forces, which included the United States of America, the British Commonwealth and the Soviet Union (USSR); a new era of geopolitical realignment began which left the US and the USSR as two superpowers with profound economic and political differences. During this post-Second World War, post-colonial period the legacy of the Great Game would sow the seeds of a new sustained state of political and military tension between the powers of the Western world, led by the United States and its NATO allies; and the Communist world, led by the Soviet Union together with its satellite states and allies. This era, coined the "Cold War", or "Great Game II" by some scholars;[2][3] was so named because it never featured any direct military action as both sides possessed nuclear weapons and their use would have probably guaranteed their mutual assured destruction. Historians trace the start of Cold War era to 1947. This was the year that decolonisation of the British Empire started which has been described as one of the focal points of Cold War evolution. Britain's withdrawal changed the dynamics of inter-Asian geopolitics, especially in Central Asia and the Middle East; leading to several conflicts including the Arab-Israeli conflict, the 1953 Iranian coup d'état and the 1958 Iraqi Revolution.[17] The USSR discovered the same bitter truth within its 1979 misadventure in Afghanistan as the British had found in the 19th Century, and withdrew its last troops from the so-called "graveyard of empires" - Afghanistan.[18][19]- in 1988. The Cold War culminated with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

The relevance of the Great Game in the Cold War context is evident in the final years of Mohammad Najibullah, the last Soviet-backed president of Afghanistan. During his 1992-96 refuge in the UN compound in Kabul, while waiting for the UN to negotiate his safe passage to India, he engaged himself by translating Peter Hopkirk's book The Great Game[20] into his mother tongue Pashto.[21] A few months before his execution by the Taliban, he quoted, "Afghans keep making the same mistake," reflecting upon his translation to a visitor.[22]

End of the Cold War to 2001[]

In the 1990s, the use of the expression "The New Great Game" in reference to classical "Great Game" appeared;[23][24][25][26][27][28] to describe the competition between various Western powers, Russia, and China for political influence and access to raw materials in Central Eurasia—"influence, power, hegemony and profits in Central Asia and the Transcaucasus".[29][30]

Many authors and analysts viewed this new "game" as centring around regional petroleum politics in Central Asian republics. Noopolitik plays a more central role than ever in the balance of power of the New Great Game;[31] and instead of competing for actual control over a geographic area - "pipelines, tanker routes, petroleum consortiums, and contracts" - are the prizes of the new Great Game.[3][29][32]

2001 to present[]

In the aftermath of the attacks on the United States on 11 September 2001, the United States invaded Afghanistan in order to aid Afghan rebels of the Northern Alliance in removing the Taliban regime which had allowed al-Qaeda to operate training camps within Afghanistan. By the end of 2001 the Taliban regime had lost control of most of the territory it had held and its leadership had crossed the border into Pakistan's tribal areas. United States forces and their NATO allies have remained in Afghanistan supporting the current regime of President Hamid Karzai. This has led to new geopolitical efforts for control and influence in the region.[33] Many commentators have either compared these political machinations to the Great Game as played out by the Russians and British in the nineteenth century, or described them as part of a continuing Great Game,[2][3] and has become prevalent in literature about the region; appearing in book titles,[32] academic journals,[30] news articles, and government reports.[34][35][36] While energy resources and military bases are mentioned as part of the Great Game, so is the continuing jostling for strategic advantage between Great powers and between the regional powers in mountainous border regions in the Himalayas. In the 21st century, the great game continues.[37]

Chronology[]

1582-1639: Russians occupy the forest zone north of Central Asia. 1717: Russians fail to take Khiva.

1735: Baskir War blocks plan to invade Central Asia.

1743: Orenburg founded. 1757: British are victorious in the Battle of Plessey in India. 1801: Russian invasion called back. About this time most of central Asia was divided between the Khanate of Khiva (south of the Aral Sea), the Emirate of Bukhara (center) and the Khanate of Kokand (east). 1810: Henry Pottinger and Charles Christie reach Isfahan from Nushki, Balochistan, Christie via Herat. 1819: Nikolay Muravyov visits Khiva. 1820(circa): Aga Mehdi or Mehkti Rafailov, Russian agent in Kashgar or Yarkand. 1821: Russians visit Bukhara. 1825: William Moorcroft (explorer) visits Bukhara.

1830: Arthur Conolly fails to reach Khiva, then travels from the Caspian to India. 1831: Alexander Burnes charts the Indus, then reaches Kabul and Bukhara. 1838: British force Persia to abandon Siege of Herat (1838). 1839: British occupy Kabul. 1840: Russian attack on Khiva fails; Abbott and Shakespear at Khiva. 1842: British expelled from Kabul with great loss, retake Kabul and withdraw (First Anglo-Afghan War); Arthur Conolly and Charles Stoddart executed at Bukhara.

1843: British annex Sindh .

1849: British annex Punjab. 1853: Russians found Kazala on the Aral Sea and Ak-Mechet to the east. 1853-56: Crimean War. 1856: British again keep Persians from Herat. 1857: Indian Rebellion. 1858: Ignatyev visits Khiva and Bukhara. 1860s and later: British agents explore north of India. 1863: Afghans annex Herat. 1864: Chernyayev takes Chimkent from Bukhara; city taken from Kokand. 1865: Chernyayev takes Tashkent which becomes the capital of Russian Turkistan. 1868: Kaufman takes Samarkand; Bukhara a protectorate; part of Zarafshan River valley annexed. 1868: George W. Hayward, Robert Shaw and a Russian at Kashgar. 1869: Krasnovodsk founded on the east side of the Caspian. 1871: Russians occupy upper Ili River.

1873: Kaufman makes Khiva a Russian protectorate. 1875: Kaufman conquers Kokand.

1877: China regains Xinjiang from Yakub Beg. 1878: Second Anglo-Afghan War.

1879: Russian defeat at Geok Tepe. 1881: Russians take Geok Tepe; Ili valley returned to China .

1884: Russians take Merv.

1885: Russians take Pandjeh south of Merv on the road to Herat. 1888: Trans-Caspian railway from Krasnovodsk reaches Samarkand; Russians in Hunza.

1891: British take Hunza. 1895: British take Chitral.

1904: Younghusband reaches Tibet. 1906: Tashkent Railway: direct rail connection to European Russia.

In popular culture[]

- Kim by Rudyard Kipling

- The Lotus and the Wind by John Masters

- Flashman by George MacDonald Fraser

- Flashman at the Charge by George MacDonald Fraser

- Flashman in the Great Game by George MacDonald Fraser (1999) ISBN 0-00-651299-2

- The Game by Laurie R. King (2004), a Sherlock Holmes pastiche, one of the Mary Russell series. ISBN 0-553-80194-5

- The song "Pink India" from musician Stephen Malkmus' self-titled album.

- The documentary The Devil's Wind by Iqbal Malhotra.[38]

- Afuganisu-tan a Webcomic by Japanese manga artist, Timaking

- Declare by Tim Powers

- The Far Pavilions by M. M. Kaye Viking Press, LLC, New York, 1978

- The plot of the James Bond film The Living Daylights partially revolves around an updated version of the Great Game. Bond's character travels to Afghanistan and convinces the local mujaheddin to turn upon the Soviet occupiers, to whom the mujaheddin had previously sold heroin.[citation needed]

Criticism[]

Gerald Morgan’s Myth and Reality in the Great Game approached the subject by examining various departments of the Raj to determine if there ever existed a British intelligence network in Central Asia. Morgan wrote that evidence of such a network did not exist. At best, efforts to obtain information on Russian moves in Central Asia were rare, ad hoc adventures. At worst, intrigues resembling the adventures in Kim were baseless rumours and Morgan writes such rumours “were always common currency in Central Asia and they applied as much to Russia as to Britain.”[39]

In his lecture “The Legend of the Great Game”, Malcolm Yapp said that Britons had used the term “The Great Game” in the late 19th century to describe several different things in relation to its interests in Asia. Yapp believes that the primary concern of British authorities in India was control of the indigenous population, not preventing a Russian invasion.[40]

According to Yapp, “reading the history of the British Empire in India and the Middle East one is struck by both the prominence and the unreality of strategic debates.”[40]

See also[]

|

|

|

References[]

Notes[]

- ↑ Also called the Tournament of Shadows (Russian: Турниры теней, Turniry Teney) in Russia.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Post Modern Imperialism: Geopolitics and the Great Games". http://www.iranreview.org/content/Documents/Post_Modern_Imperialism_Geopolitics_and_the_Great_Games.htm. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Walberg, Eric. Postmodern Imperialism: Geopolitics and the Great Games". http://ejas.revues.org/9709. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ Hopkirk, Peter (1992). The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia, p. 1

- ↑ Morgan, Gerald. “Myth and Reality in the Great Game” Asian Affairs 4:1 (1973) 55-65.

- ↑ "When Will the Great Game End?". orientalreview.org. 15 November 2010. http://orientalreview.org/2010/11/15/when-will-the-great-game-end/. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ Gandamak at britishbattles.com

- ↑ Mahajan, Sneh, British Foreign Policy, 1874–1914, p. 53

- ↑ International Boundary Study of the Afghanistan-USSR Boundary (1983) by the US Bureau of Intelligence and Research

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Robert Middleton, The Earl of Dunmore 1892–93 (2005)

- ↑ Forty-one years in India – From Subaltern To Commander-In-Chief, Lord Roberts of Kandahar – The Hunza-Naga Campaign

- ↑ Tamm, Eric Enno, "The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds: A Tale of Espionage, the Silk Road and the Rise of Modern China", p. 3

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Tamm, Eric Enno, "The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds: A Tale of Espionage, the Silk Road and the Rise of Modern China", p. 4

- ↑ Tamm, Eric Enno, "The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds: A Tale of Espionage, the Silk Road and the Rise of Modern China", p. 353

- ↑ Lloyd, Trevor Owen, "Empire: The History of the British Empire ", p. 142

- ↑ Hopkirk, Peter (1992). The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia, p. 520

- ↑ List of modern conflicts in the Middle East

- ↑ "The 'Great Game' of influence in Afghanistan continues but with different players". Fox News. 9 June 2012. http://www.foxnews.com/world/2012/06/09/great-game-influence-in-afghanistan-continues-but-with-different-players/. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ Farndale, Nigel (30 May 2012). "Afghanistan: the Great Game, BBC Two, review". telegraph.co.uk. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/tvandradio/9299771/Afghanistan-the-Great-Game-BBC-Two-review.html. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ "The Great Game: The Myth and Reality of Espionage". CIA.gov. http://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/vol48no3/article08.html. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ "Executed Afghan president stages 'comeback'". 22 June 2012. aljazeera.com. http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2012/06/2012618134838393817.html. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ↑ Coll, Steve (2004). "Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the Cia, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001", p. 333

- ↑ Geyer, Georgie Anne (17 February 1992). "U.S. Flag Waves Inside A Proud New Nation". Universal Press Syndicate. http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19920217&slug=1476243.

- ↑ Sneider, Daniel (5 May 1992). "New 'Great Game' In Central Asia". The Christian Science Monitor. http://www.csmonitor.com/1992/0505/05011.html.

- ↑ "The New Great Game in Asia". The New York Times. 2 January 1996. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C06E4D61539F931A35752C0A960958260.

- ↑ Ahrari, Mohammed E.; James Beal. "The New Great Game in Muslim Central Asia". McNair Paper 47. Institute for National Strategic Studies and National Defense University.

- ↑ Cohen, Ariel. "The New "Great Game": Oil Politics in the Caucasus and Central Asia". Backgrounder #1065. The Heritage Foundation.

- ↑ Ahmed, Rashid. "Central Asia: Power Play". Far Eastern Economic Review

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Brysac, Shareen; and Meyer, Karl. Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Asia. Basic Books. pp. 704.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Edwards, Matthew. "The New Great Game and the new great gamers: Disciples of Kipling and Mackinder". Central Asian Survey 22 (1): 83–103

- ↑ "An Optimistic Memo on the Chinese Noopolitik: 2001-2011". Idriss J. Aberkane. e-ir.info. 13 June 2011. http://www.e-ir.info/2011/06/13/an-optimistic-memo-on-the-chinese-noopolitik-2001-2011/.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Rashid, Ahmed. (2000), "Taliban: Islam, Oil and the New Great Game in Central Asia."

- ↑ Cooley, Alexander. "Great Games, Local Rules: The New Great Power Contest in Central Asia", 53

- ↑ Melik Kaylan (13 August 2008). "Welcome Back To the Great Game". Wall Street Journal. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB121858681748935101.html.

- ↑ "Candid discussion with prince andrew on the kyrgyz economy and the "great game"". Wikileaks. 29 October 2008. http://wikileaks.ch/cable/2008/10/08BISHKEK1095.html.

- ↑ Menon, Rajan. "The New Great Game in Central Asia". Survival: Global Politics and Strategy 45 (2), Rajan Menon : 187–204

- ↑ In the 21st century the great game continues:

- Economist staff (22 March 2007). "The Great Game revisited India and Pakistan are playing out their rivalries in Afghanistan". The Economist. http://www.economist.com/node/8896853.

- Rubin, Barnett R.; Rashid, Ahmed (November/December 2008). "From Great Game to Grand Bargain: Ending Chaos in Afghanistan and Pakistan". Council on Foreign Relations. http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/64604/barnett-r-rubin-and-ahmed-rashid/from-great-game-to-grand-bargain. "The Great Game is no fun anymore".

- Ivens, Martin (24 January 2010). "More guile needed in the Afghan game". London. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/columnists/martin_ivens/article6999979.ece. "The new strategy proposed by the US commander in Afghanistan... A settlement of outsiders as well as insiders is also vital. Pakistan, India, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Russia and China have to have a stake in a deal or they will have an incentive to break it."

- Jaswant Singh (25 September 2010). "China and India: the great game's new players". London. http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2010/sep/25/china-india-great-game.

- Reuters (25 October 2010). "The "Great Game" bubbles under Obama's India trip". http://tribune.com.pk/story/67452/the-great-game-bubbles-under-obamas-india-trip/.

- Editorial (27 October 2010). "Leading article: Nato's Afghan endgame begins with a helping hand from Russia". London. http://www.independent.co.uk/opinion/leading-articles/leading-article-natos-afghan-endgame-begins-with-a-helping-hand-from-russia-2117150.html.

- ↑ DocsOnline Docsonline.tv

- ↑ Morgan, Gerald. "Myth and reality in the great game". Asian Affairs 4 (1): 55-65

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Yapp, Malcolm. "The Legend of the Great Game”, Proceedings of the British Academy. pp. 179–198

Bibliography[]

External links[]

| ||||||||||||||||||||

The original article can be found at The Great Game and the edit history here.