Walter W. Horn (18 January 1908 – 26 December 1995) was a medievalist scholar noted for his work on the timber vernacular architecture of the Middle Ages. He was born in Germany, but fled Nazism and spent most of his academic career at the University of California, Berkeley, where he became the university system's first art historian and co-founded the History of Art department. A naturalized citizen of the United States, Horn served in the U.S. Army during World War II and then in the special intelligence unit that tracked down art works plundered by the Nazis. His most celebrated exploit was the recovery of the crown jewels of the Holy Roman Empire, also known as Charlemagne's Imperial Regalia.[1] As a scholar, Horn is most noted for his work on the medieval architectural drawing known as the Plan of Saint Gall.

Early life[]

Horn was born in the town of Waldangelloch in rural Baden. His mother was Matilde Peters; she married Karl Horn, a Lutheran minister. Walter attended a Gymnasium in nearby Heidelberg and went on to study art history at the University of Heidelberg and the University of Berlin. He earned his doctorate in 1934 at the University of Hamburg, studying under Erwin Panofsky. His dissertation, Die Fassade von Saint-Gilles, on the façade of Saint-Gilles, Gard, was published in 1937.

World War II era[]

As a special intelligence officer, Horn recovered the "crown of Charlemagne", part of the Imperial Regalia hidden by the Nazis

Horn fled Germany in opposition to the Nazi regime. He continued his studies from 1934 to 1937 as a research associate at the German Institute for the History of Art in Florence, Italy. In 1938, Horn moved to the United States and began his long association with the University of California, Berkeley, as a lecturer. A year later, he was given a permanent position as the first art historian in the University of California system.[2] During this time, he married Ann Binkley Rand.

Horn became a naturalized citizen in 1943. That same year, he volunteered for military duty in the U.S. Army. By 1945, he was a lieutenant in the Third Army under General George S. Patton. Horn's skills as a native speaker of German were put to use in interrogating prisoners of war. After the war, he continued as a special investigator in the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program, using his expertise as an art historian to track down art that had been stolen or concealed by the Nazis. Horn served until 1946, attaining the rank of captain.

In 1946, Horn succeeded in recovering the Imperial Regalia of Charlemagne, the crown, sceptre, and jewels of the Holy Roman Empire. These had been kept hidden by Germans who hoped to return to power even after their defeat by the Allies. [3] The incident has been elaborated, sometimes with inaccuracies, by writers who take particular interest in the Holy Lance, the spear supposed to have pierced the side of Jesus during his crucifixion. This artifact is sometimes called the Spear of Destiny and identified with the Vienna Lance, one of the components of the regalia. In speculative works of non-fiction that endow the lance with occult powers or mystical significance in Nazism,[4] Horn appears in narratives about its retrieval from the possession of Adolf Hitler.[5] Usually identified as "Lt. Walter William Horn," he is said to have retrieved the lance at the behest of Patton on the very day of Hitler's death, that is, 30 April 1945.

The McCarthy era[]

Returning from the war, Horn married Alberta West Parker, a physician, who became a Clinical Professor of Public Health at UC Berkeley.[6] In 1949, Horn and his family became embroiled in the controversy at his university over a loyalty oath requirement. During the era of the Cold War, the Red Scare, and McCarthyism, the Board of Regents at the University of California began to require that all university employees sign an oath affirming their loyalty to the state constitution and denying their membership or belief in organizations advocating the overthrow of the U.S. government. The requirement met with resistance, and in the summer of 1950 thirty-one professors[7] who refused to sign were fired, despite their stature as "internationally distinguished scholars."[8] Horn's fellow medievalist Ernst Kantorowicz resigned rather than sign the oath, stating his reasons in two letters to the university president that were only published in English decades after the episode. Kantorowicz also presented a letter from Horn, who had signed the oath under protest. In the letter dated 23 August 1950, Horn, then acting chairman of the art department, pointed to his former military service and to his voluntary reactivation that same month as a reservist in the Armed Services.

| “ | Being thus confronted a second time with a disruption of my academic career, and feeling unable to expose my wife and my son to the consequences of being denied continuance of my civilian occupation upon return from military duty, it is with profound regret that I find myself compelled to yield to the pressure which the Regents saw fit to exercise in order to extort from me a declaration concerning my political beliefs. I am enclosing the requested statement, signed. I should like to make known that, in doing so, I am acting against the better precepts of my conscience and for no other reason than that of protecting my family against the contingencies of economic distress. … It was in avoidance of pressures of this type that I left Germany in 1938 and came to this country. And it was in the desire of contributing to the eradication of such methods that I volunteered during the last war to take up arms against the country of my birth. I am expecting my recall to active duty in the present conflict with the bitter feeling that, this time, I shall be fighting abroad for the defense and propagation of Freedoms which I have been denied in my professional life at home. | ” |

Kantorowicz noted that Horn's letter "illustrates the grave conflict of conscience and savage economic coercion to which, after fifteen months of pressure and struggle, he had finally to yield."[9]

Academic career and scholarship[]

Horn established methods for dating with his work on the Florence Baptistry

Great Coxwell Barn was one of two Cistercian structures studied by Horn and Ernest Born for their first book

Horn's early position as research associate in Florence gave him firsthand knowledge of the city's medieval church architecture and produced two important studies, Das Florentiner Baptisterium (1938), an analysis of the fabric and ornamentation of the Florence Baptistry that established new criteria for its dating, and Romanesque Churches in Florence: A Study of Their Chronology and Stylistic Development (1943), which included an examination of the masonry construction of San Miniato al Monte. Throughout his career, he continued to explore the conceptual connections between classical and northern architecture.[10] His specialty was three-aisled timber structures in medieval churches, market halls and manor halls. He was known for arriving at a precise dating of medieval buildings through studying their technologies and observing the physical evidence, drawing on scientific disciplines; he dated timber structures with reference to radiocarbon analysis and dendrochronological tables.[11]

In 1958, Horn published what is considered his most important article,[12] “On the Origins of the Medieval Bay System” in the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. He argued that bay-divided medieval churches derived from Germanic timber buildings and represented a continuous tradition of vernacular architecture in transalpine Europe. Horn was the first to assemble the known timber examples, which dated from as early as 1200 BC and extended into the medieval period. Because traces of early wooden structures were often scanty or oblique, Horn used scientific methods to uncover their architectural principles, and demonstrated that these were developed and applied to stone cathedrals in the Romanesque and Gothic periods.[13]

The 1958 article was significant also in that it marked Horn's first collaboration with Ernest Born, the San Franciscan architect and draftsman with whom he was to author a series of books and articles over the next twenty years. Their first book was The Barns of the Abbey of Beaulieu at Its Granges of Great Coxwell and Beaulieu St. Leonard (1965), a study of the only two Cistercian tithe barns, dating from the 13th century, that survive in England.[10] But their major project was the three-volume work The Plan of St. Gall: A Study of the Architecture and Economy of, and Life in a Paradigmatic Carolingian Monastery, which has been called "one of the greatest monographs on medieval architecture that has ever appeared."[14]

Plan of St. Gall[]

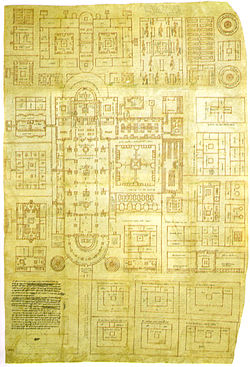

The Plan of Saint Gall

The plan of Saint Gall had engaged Horn's imagination and curiosity since he was introduced to it by his mentor Erwin Panofsky.[15] In 1957, Horn had participated in an international congress on the plan, and his interest in its guest and service buildings led to his survey of medieval structures in France and England. In 1965, Horn and Born contributed to the creation of a scale model of the 40 buildings rendered on the plan. The model was displayed at the international exhibit Karl der Grosse held at Aachen. Their two decades of collaboration culminated in a work of 1,056 pages with an estimated 1,200 illustrations.

The Plan of St. Gall was praised by French historian Emmanuel LeRoy Ladurie for its "prodigious scholarship," and for its wide-ranging elucidation of Carolingian daily life.[16] The first volume offers a reconstruction of the church and the living quarters for a community of monks numbering about a hundred. The second volume covered the guest and service buildings and the horticultural spaces for growing vegetables, medicinal herbs, and fruit and nut trees. The third volume contains supplemental material such as Horn's 88-page catalogue of the plan's explanatory tituli, or captions, and Charles W. Jones' English translation of the Consuetudines Corbienses by Adalhard of the abbey of Corbie.[17] Through meticulous reimagining of the activities that the architecture was meant to facilitate, Horn presents a rich picture of Carolingian life and thought.

The most controversial aspect of the work was Horn's major thesis: that the plan was a copy of a lost master plan dating to 816 or 817 that would have been part of documents pertaining to the official monastic reform movement under Louis the Pious at Aachen. The dominant strand of criticism to the contrary holds that the plan was intended to represent an ideal and was never meant to be carried out at a particular site. Horn's last article on the plan, "The Medieval Monastery as a Setting for the Production of Manuscripts,"[18] was a response to this criticism.[14]

The Plan of St. Gall earned twelve major awards for its scholarship, bookmaking, and typography, including a prize from France's Académie d'architecture and a 1982 medal from the American Institute of Architects.[19]

Later work[]

In 1974, Horn retired to emeritus status after 36 years at the University of California. His last publication, The Forgotten Hermitage of Skellig Michael (1990), co-authored with Jenny White Marshall and Grellan D. Rourke, resulted from fieldwork begun in 1978 on Ireland's Atlantic offshore islands. His interest in the Celtic roundhouse had been indicated earlier in "On the Origins of the Medieval Cloister" (1973).

Honors and administrative achievements[]

Horn worked with classical archaeologist Darrell A. Amyx to establish History of Art as a separate department at the University of California in 1971. He was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (elected 1970) and of the Medieval Academy of America (1980). Horn was an active supporter of arts institutions outside academia, serving as trustee of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and chairman of the museum's acquisitions committee.[20] He was on the board of the College Art Association 1950–54 and 1964–68 and on the board of the Society of Architectural Historians 1964–68.

Death[]

Horn died at home of pneumonia on Tuesday, 26 December 1995, at Point Richmond, California. He was 87. He was survived by his wife, Alberta; his son, Michael; two daughters, Rebecca and Robin; and a grandson, Matthew. His obituary in the New York Times labeled him "historian of medieval cloisters and barns."[16] Horn was remembered by colleagues as one of the university's "best-loved and most influential teachers and … most effective leaders."[21] He was eulogized for "his oratorical skills and uncanny ability to bring the medieval building or pile of ruins vividly to life. His eloquence and grace matched his endless curiosity about prehistoric and medieval buildings in northern Europe and how people utilized them."[22]

Selected bibliography[]

Standard biographical and publishing data on Horn not otherwise cited comes from two or more of the following sources.

- W. Eugene Kleinbauer, James Marrow and Ruth Mellinkoff. "Memoirs of Fellows and Corresponding Fellows of the Medieval Academy of America: Walter W. Horn," Speculum 71 (1996) 800-802.

- University of California (System) Academic Senate, "1996, University of California: In Memoriam," "Walter Horn, History of Art: Berkeley"

- Dictionary of Art Historians: A Biographical Dictionary of Historic Scholars, Museum Professionals and Academic Historians of Art, "Horn, Walter W(illiam)."

- William Grimes, "Walter Horn, 87, a Historian Of Medieval Cloisters and Barns," New York Times 29 December 1995, obituary

- "Walter Horn," San Francisco Chronicle, 30 December 1995, obituary

- "Walter Horn; Specialist in Medieval Architecture," Los Angeles Times, 31 December 1995, obituary

- Rihoko Ueno, A Finding Aid to the Walter Horn Papers, 1908-1992, bulk 1943-1950, in the Archives of American Art, Washington, DC 2012.

- Brown, Hillary, Finding Aid for the Walter Horn Papers, 1917-1989, at the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, 1997.

References[]

- ↑ W. Eugene Kleinbauer, James Marrow and Ruth Mellinkoff, "Memoirs of Fellows and Corresponding Fellows of the Medieval Academy of America: Walter W. Horn," Speculum 71 (1996), p. 800 ("his most important piece of detective work led to the recovery of the coronation regalia of the Holy Roman Empire"); "Walter Horn," San Francisco Chronicle, 30 December 1995, obituary; University of California (System) Academic Senate, "1996, University of California: In Memoriam," "Walter Horn, History of Art: Berkeley" ("his most spectacular feat was the recovery of Charlemagne's ceremonial regalia").

- ↑ UC In Memoriam, p. 87.

- ↑ UC In Memoriam.

- ↑ See Trevor Ravenscroft, The Spear of Destiny: The Occult Power behind the Spear Which Pierced the Side of Christ (Red Wheel, 1982). Ravenscroft reproduces a portion of Horn's report on the recovery of the regalia (called there "insignia"), p. 348. For issues raised by Ravenscroft's methodology, see Holy Lance: Trevor Ravenscroft.

- ↑ A detailed version by Jerry E. Smith and George Piccard, Secrets of the Holy Lance: The Spear of Destiny in History and Legend (Adventures Unlimited Press, 2005), pp. 267–270 online; see also E. Randall Floyd, 100 of the World's Greatest Mysteries (Harbor House, 2000), pp. 262–263; Lionel Fanthorpe and Patricia Fanthorpe, Mysteries and Secrets of the Templars: The Story behind the Da Vinci Code (Dundurn Press Ltd., 2005), p. 57.

- ↑ San Francisco Chronicle, March 31, 2012, Alberta Horn, obituary

- ↑ Along with a number of other employees.

- ↑ The University Loyalty Oath.

- ↑ Horn's letter appears following two letters by Kantorowicz at The University Loyalty Oath: A 50th Anniversary Retrospective, "The Fundamental Issue."

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Walter Horn, History of Art: Berkeley"

- ↑ Kleinhauer et al., "Memoir," p. 801. See, for example, Walter Horn, "The Potential and Limitations of Radiocarbon Dating in the Middle Ages," in Scientific Methods in Medieval Archaeology, edited by Rainer Berger (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1970), pp. 23-87.

- ↑ Kleinhauer et al., "Memoir," p. 800.

- ↑ Kleinhauer et al., "Memoir," p. 800; "Walter Horn, History of Art: Berkeley"; Dictionary of Art Historians.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Kleinhauer et al., "Memoir," p. 801.

- ↑ Kleinhauer et al., "Memoir," p. 800.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 William Grimes, "Walter Horn, 87, a Historian Of Medieval Cloisters and Barns," New York Times 29 December 1995, obituary

- ↑ See Charles W. Jones for more on this collaboration.

- ↑ Co-authored with Born in the Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 44 (1986) 16–47.

- ↑ Kleinhauer et al., "Memoir," p. 801; Grimes, NYT obituary.

- ↑ San Francisco Chronicle, 30 December 1995, obituary "Walter Horn."

- ↑ "Walter Horn, History of Art: Berkeley," Calisphere.

- ↑ Kleinhauer et al., "Memoir," pp. 801–802.

The original article can be found at Walter Horn and the edit history here.